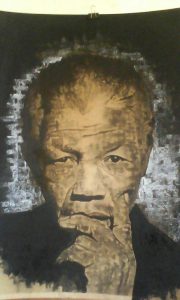

As the Facebook page loads, the first thing that grabs my attention is the painting of Nelson Mandela set as the cover photo. It is a portrait that adorns many walls throughout South Africa, and an image saturated with so many different emotions. Madiba is regarded as a hero by most, but now his legacy is viewed less positively by an increasing number of young South Africans. The various debates I have observed on the topic spring to mind, and I am instantly aware of my own biases which condition how I will view this page before it has even loaded.

The profile photo of the page features the initials of the organization in the bright colours of the South African flag. The imagery and colours of the page are warm and welcoming and assert the message, “proudly South-African”.

This is the home of The South African Arts & Culture Youth Forum (SAACYF) Facebook page. The page aims to promote the development of local up-and-coming artists. It consists of various posts calling for an increased focus on and support for local art, claiming that the South African government has for too long drawn attention to predominantly international artists.

One of the first posts on the page discusses how many South African people choose to follow Western culture only. The post says that they “believe that everything that is white and foreign is superior and better than everything that is South African”. In another post, the page discusses what they believe is the overbearing influence of white capitalists on the art and culture landscape in South Africa. As I go through the posts, I can quickly recognise my own subjectivity. I am a white South African who, simply because of my race, benefits from the current economic disparity that is so pervasive in the country. Until a few years ago, most of the art and culture I consumed was either from the West or was heavily influenced by it.

This was not a conscious decision. My patterns of consumption were a result of my circumstances and the environments I frequented. It has only been in recent years, and likely as a result of new governmental promotions of local art and culture, that I have begun to interrogate what I consume and made efforts to support local artists and embrace South African culture. It is only through acknowledging this change in my own consumption that I can recognise the need to support local artists, and have since become a fervent supporter of the South African arts and culture scene.

Attending a tertiary institution in South Africa has also allowed me to grapple with my privileges as a white woman. The ideas raised on the page and the efforts to shift the focus away from foreign art might be perceived by a non-South African as animosity towards foreigners or white people. Although the discourse on the page vehemently rejects foreign art and culture in ways I might have questioned or challenged, I now often choose to locate myself as a listener during these debates in an attempt to acknowledge that the position I occupy in society automatically limits my ability to understand the prosaic realities of, in this case, being a South African artist.

This does pose a potential risk for me and the way I write about it, because I am predisposed to support such calls for a shift in the focus towards locally-produced art. But, I think as long as I engage with this bias in my writing, my subjectivity can be noted and can provide an alternative angle from which to view the page and the movement as a whole.

As a journalism student, I was often taught to be objective, but it was impressed upon us that one can never be fully objective. In the pursuit of being fully objective, one will likely adopt what Rosen (2010) terms, “the view from nowhere”, and so the research becomes less meaningful. In the process of creating journalistic content, including investigating, fact-checking and immersing oneself in one’s beat, one will inevitably develop an opinion on the topic (Rosen, 2010). Discussing that opinion does not decrease the credibility of the piece or one’s own professionalism. Aiming for transparency rather than objectivity and showing where the author’s view comes from serves to increase their authority on the subject (Rosen, 2010).

The researcher of course has a responsibility to try to abandon ethnocentrism and view things holistically, but there is still value in bias – as long as we acknowledge it.

Reference list:

Rosen, Jay. 2010. “The View from Nowhere: Questions and Answers.” PressThink, November 10. Retrieved on 19 February from http://pressthink.org/2010/11/the-view-from-nowhere-questions-and-answers/.

Mirjam de Bruijn

September 24, 2020 (07:03)

This is a good reflection on your own position and hence a good start for researching Africa. I am a little lost in the observational part and the ‘thick description’.