A stroll from the Westerkerk along the Keizersgracht, towards number 141, to the canal house with its stone steps, dark green balustrade and monumental front door, yields a street scene that is not very different from a setting of fifty years ago. Although car traffic is largely banned from Amsterdam’s city center, delivery vans and automobiles are allowed to drive along the canals, just as it was then. There are the cyclists, the odd motorboat, the locals walking their dogs and the manager of the cafe on the corner scrubbing his sidewalk. I imagine it was very similar when South African writer Karel Schoeman walked here, as I do, while visiting the Zuid-Afrikahuis at number 141. Schoeman came to the institute’s library regularly when he lived in Amsterdam in the late 1960s and early 1970s during a five year period of self chosen exile.

There is a flag posted on the building with the name of the institute on it, a pale cloth enlightened with orange letterings. I am not sure whether the house presented itself in this fashion during the 1970s. After all, South Africa had a bad reputation in the Netherlands in those years; as a good Dutchman you really didn’t want to have much to do with South-Africa due to the unfortunate political situation of the apartheid regime. But now, with the peaceful, lazy waving of the sallow flag, it’s hard to picture the canal house being a center of violence, which sometimes occurred when Dutch activists forced themselves in, as it happened for instance in January 1984, when many of the books were tossed into the canal.

None of the pedestrians, joggers, bikers and drivers are probably aware of this memory, it’s just me in my subjectivity, carrying those thoughts during my walk towards the mansion. My footsteps sound clear and hollow on the paving stones. Behind me the bells of the Westerkerk ring twelve. I climb the six steps of the stone staircase en press the tiny button on the brass holder, just left of the shiny door. Someone inside on the first floor handles a switch that opens the door lock, which can only be noticed if you listen carefully because the buzzer, that signals the visitor to enter, makes hardly any sound. If you miss the signal, you will find yourself pushing the door in vain and you’ll have to ring the bell again. The front door is heavy and once inside you find yourself in a narrow corridor lined with marble. To the left is a modern looking wooden staircase, that winds in a twist to the upper floor. To the right is a door that, when it stands open, allows a view into a large room with a high, plastered, decorated sealing that betrays the richness of the original builders of the residence. This mansion’s past is built up of many layers of identities, histories and memories.

My visit leads upwards, via the curved staircase, towards the desk of the librarian, who will hand me the scrapbooks with the paper cuttings that I’ve ordered online. But first I have to hang up my coat on one of the racks, just left on the landing with its soft, beige carpet. The landing’s open bookcase shows the library’s latest acquisitions, like As jy van moord droom en Has China won? South-Africa, that array of land at the southern tip of the vast African continent, remains the home of a society of ever revolving transition which is mirrored in the almost unreal, Dutch setting at the Keizersgracht.

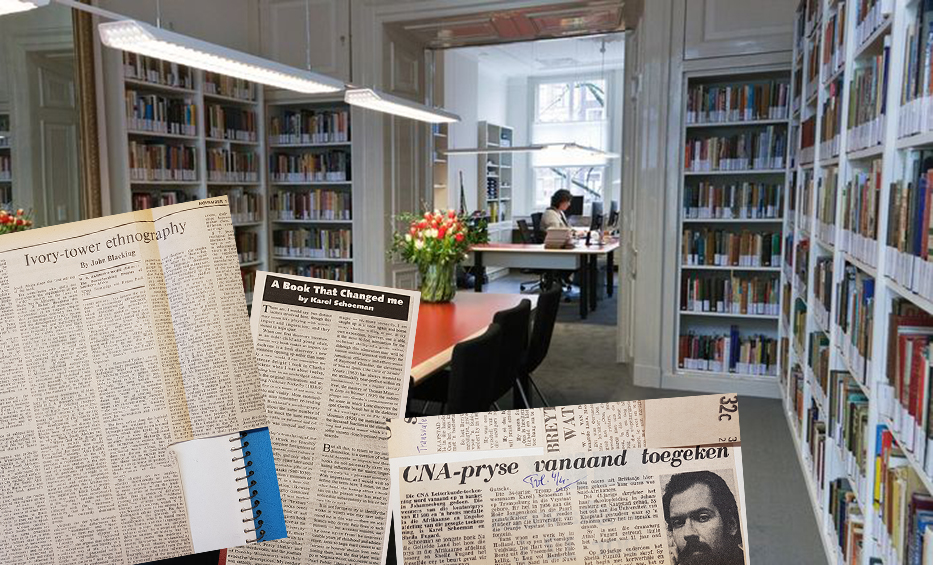

The librarian hands me the pile of scrapbooks with a smile and I take a seat at the large wooden table with its read coating in the adjoining reading room. The surface of the table is split up in several units by the plastic screens that measure out one and a half meters distance as a sign of the reality of the current times. I cannot spread my books all over the table like I used to, I have to stay confined within the space that is given to me by the screens. But the view from the windows into the garden with its shrubs, trees and sky and, in front of me, of the marble mantelpiece and its large overhanging mirror is the same as ever. When I open one of the scrapbooks there is a faint smell of old newspapers, as if the pages were stuck together for a long time, and I wonder how often these clippings are being consulted by researchers. The content certainly has the look and feel of a rarely studied treasure. My search for traces of Karel Schoeman are rewarded. There is a rare article by him concerning books that influenced him and accordingly changed his life. Am I now going to read the books that he mentioned and see what they will do to me, I wonder? Probably, but I’m not sure. One of the listed books is The story of an African farm by Olive Schreiner, an author that Schoeman sometimes quoted in his emails to me, not long before he passed away in May 2017.

In the hours that pass during my steady browsing through the papers, I look around the room, to the hundreds of books that line the walls. There’s almost a whole shelf dedicated to the many biographies of Nelson Mandela and I also spot the written life stories of well known South African writers, like Breyten Breytenbach, Laurens van der Post and Jan Rabie. Schoeman’s autobiography Die Laaste Afrikaanse Boek is also there. It was here, in the Zuid-Afrikahuis where Schoeman discovered the truth about the socio-political situation in his native country. This library gave him the opportunity to borrow and read books about South Africa that were forbidden and banished in the country itself. Censorship during apartheid was fierce. But these readings in the Zuid-Afrikahuis opened his eyes to the social realities of the discriminatory system. To get a clear view of South Africa was better outside the country than inside. Distance proved to be a major factor in gaining knowledge. So after all the idyllic setting at the Keizersgracht was and is not so unreal after all in offering insight into the troubled society under the Southern Cross.

Mirjam de Bruijn

September 23, 2020 (20:22)

Nice description of a discovery that in fact was already known to you; didi ethnographic approach lead to new isights? also in the sense that it made you reflect differently?

Ria Winters

September 29, 2020 (12:14)

Yes, by observing all the biographies around me I was more aware of all the different virtual ‘voices’ in the room.