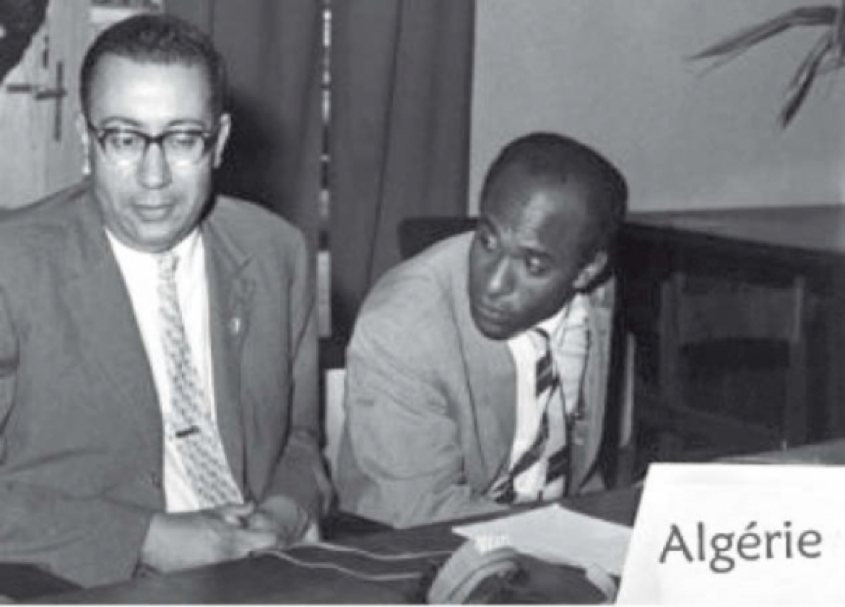

This project has sought to analyse the impact and actions of the Congo Crisis from a specific lens, focussing on those actors, many from within the Continent who had important relationships with Lumumba, who each saw the Crisis develop in different ways, had differing opinions and most importantly, different outcomes. In choosing to look at Algeria and their involvement in the Crisis, and notably that of Moïse Tshombe and the role he played, it makes sense to provide a Fanonian angle to the crisis, and one that perhaps one finds in Sapin’s painting itself. Whilst Fanon does have physical connections in the Crisis, with his presence at the Inter-African Conference of 1960, having been called upon by Lumumba as described in this project, it is more through his personal writings and work on the need for liberation in the form of African Unity and the promotion of Pan-Africanism in order to counter the evils of imperialism that come to the fore in the crisis as motivators and explanations for the events that took place. This is undeniable given the FLN’s refusal to allow Lumumba’s assassination to go “scotch free” as it were, rather finding retribution in different means and with their own agendas attached.

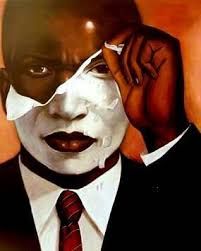

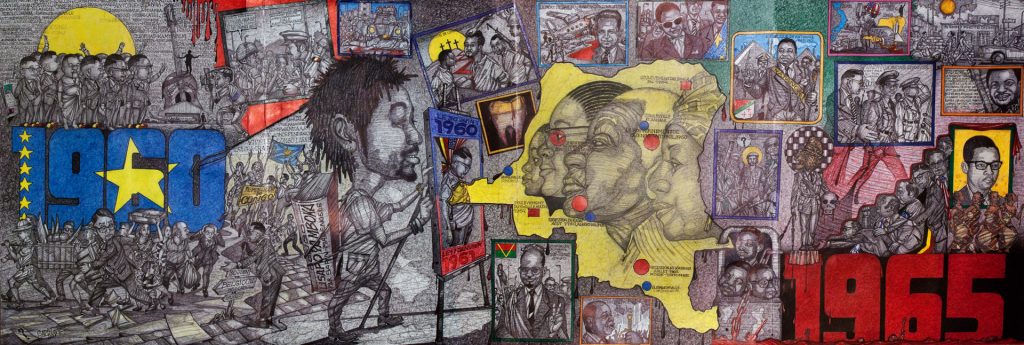

What it perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Fanon nexus, also find in the title of this project, is the psychological aspect of the Congo Crisis and how Fanon had foreshadowed some of the actors that would pursue their goals at the behest of their fellow brethren through what Fanon describes as the “internalisation of hatred that stems from an inferiority complex bound upon oneself directly as a result of the lived experiences of colonisation” (Fanon, 1967). Fanon further goes on to claim that from the Congo Crisis depicted in Sapin’s painting, a new crisis would emerge, one where the Congo makes a stark choice between “moving forwards or backwards” and that the enemy to African Unity is not simply the Occidental powers, but that of traitors from within, with direct reference to the actions that took place in Katanga (Fanon, 1964).

This is the part of Fanon’s work which interests me the most in relation to the Congo Crisis, and one of the biggest questions raised from this project is that of Moïse Tshombe, does he fit the category that Fanon refers to as being the “traitors from within” or the one with the “white mask despite his black skin”?, alongside the level of extent to which his role in the Congo Crisis had on shaping Congo’s future.

In raising the work of Fanon and relating it to the actions that took place in the Congo Crisis, one also sees great parallels between his influential work and that of those producing historiography on the Congo Crisis, often through means such as art as shown in this project’s attempt to analyse Sapin’s Congo Crisis painting. Despite having grown up in Congo after the end of the Congo Crisis, Sapin is someone who has evidently lived through its aftermath and this has had a significant influence on his historiography as one can see above. The ability to collectively share memory, and different memories of different truths, is one that should continue to be spread through alternative means such as art and through media forms such as the internet as not only do they give everyone who has lived through such experiences a voice, but it radically changes the way history is understood for the better. This was made unequivocally evident by Sapin himself in addressing the various different sections of his painting and the reasons and influences behind his depictions of the moments that make up the Congo Crisis (Sapin, 2017).

Not only is this incredibly important in the sharing of the multiple truths that exist in history as done by Sapin, but this also relates back to Fanon’s notion of what the post-colonial nation state should look like, arguing that accepting the Westphalian idea should not simply be the be all and end all of what defines a free nation, but a greater understanding of the complexities that are shared within these communities, based mainly on the need for “new ways of thinking” (Fanon). I personally find these quotes rather pertinent to the aim of this project and the greater movement towards somewhat “democratising” history in a new age, which accepts modern forms of historiography and the various different avenues that one finds such forms of history produced.

References:

- Alger, la Mecque des révolutionnaires. Directed by Mohamed Ben Slama & Amirouche Laïdi. ARTE: 2017

- Byrne, Jeffrey James. Mecca of Revolution: Algeria, Decolonisation and the Third World Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2016

- Chomé, J. Nouvel Episode au Congo-Kinshasa: La Dictature du General Mobutu Pourrait Favoriser l’Implantation des Intérêts Americaines. Le Monde Diplomatique. Aug: 1966

- De Witte, Ludo. The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba. London: Verso Books. 2002

- Fanon, Frantz. Towards the African Revolution. New York: Grove Press. 1964

- Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press. 1967

- Gibbs, David. Dag Hammarskjold, the UN and the Congo Crisis of 1960-61: A Reinterpretation. Journal of Modern African Studies 31:1 (1991)

- Hoskyns, Catherine. The Congo Since Independence, Jan 1960 – Dec 1961. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1965

- Kanza, Thomas. The Rise and Fall of Patrice Lumumba: Conflict in the Congo. Vermont: Schhenkman Books. 1994.

- Lefever, Ernest. Crisis in the Congo: A United Nations Force in Action. Washington: The Brookings Institution. 1965

- Mavuba, Alqis. La Force de Regarder Demain. Lumumba Library: Expo Peintues Populaire du Congo. Bruxelles: 2016

- Moyo, Rudo. The Blind Child: Experiences Public Life. USA: Author House. 2008

- Mortimer, Robert. Global Economy and African Foreign Policy: The Algerian Model. African Studies Review. 27:1 1984