« Le ‘quelconque’ et l’’ordinaire’ sont mes alliés »

(Miller, 2005, 17)

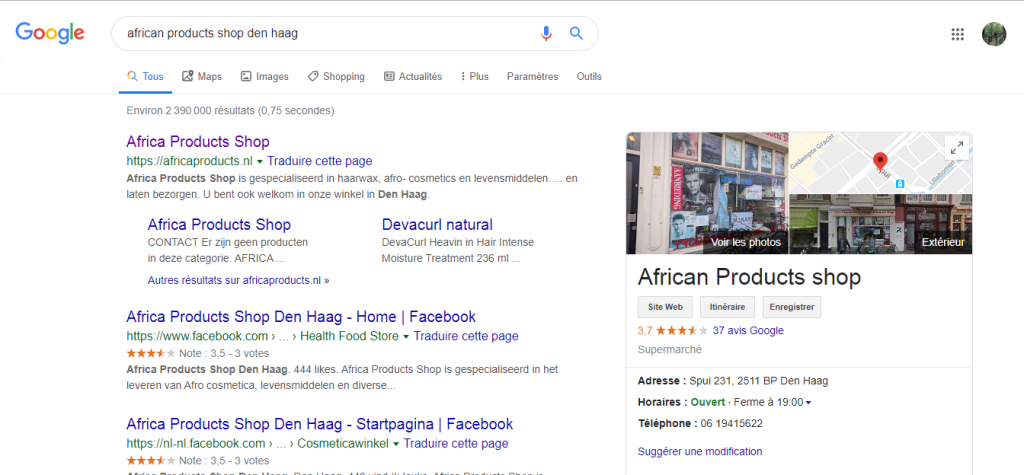

Throughout the semester, and as part of several of our assignments for the course “Researching Africa in the Twenty-First Century”, Ning Yi Boline and I agreed to take the African Products Shop located on Spui 231 in The Hague as our main research object. This independent Rwandan-owned shop constituted our gateway to African cultures in this very international Dutch city.

Consuming African cultures in the Hague

When we were given the theme for the final group project, Africa in The Hague, I immediately thought about looking at African businesses. I had explored the Haagste Markt for an ethnographic blog earlier and started grasping the deep social implications of business interactions and local businesses which I found fascinating. The topic seemed even more relevant knowing that I am a customer of these cultural businesses at home and maybe even more frequently when abroad.

Although at the start we were considering studying different sales points across the city, we eventually decided on looking solely at the African Products Shop and on the consumer side in order to be able to deliver an in-depth analysis of one single and specific case of a space of African cultures consumption in the city. To that end, we attempted at answering the following questions: Why do people decide to consume products from independent African owned shops in the The Hague? What does it mean for consumers?

Consequently, we draw an overview of the clientele characteristics. We identified the most preferred product ranges and experienced the atmosphere that makes people physically come to the shop (instead of going online or going to a regular supermarket). And, we tried to understand the meaning of the purchase and the consumption of such products and experiences. Our final thoughts and findings are made available in a blog post, combining video clips and writing.

Our work derives from sociological and ethnographic studies conducted on “ethnic” business (Ma Mung et al, 1992; Aduebert, 2007). However, we refused to use this terminology as it contributes to make these communities belong to the otherness. Also, we realized that studies often overlook what these businesses represent or mean for their customers. That is what we explored.

Experiencing the Fieldwork and the Research Process

Fieldwork was a peculiar experience. It is the first time that I conducted most of the research in a limited enclosed space. For this project, all the research work, aside from the introductory literature review, was done directly inside the African Products Shop. We visited the shop six times over the semester. We interviewed the owner of the shop in the back office. We interviewed customers directly in the aisles of the store. And, we would wait around discussing with passers-by and getting some video footage in these aisles as well.

This combination of a confined field space with the repetition of our visits gave us the opportunity to improve the overall quality of our research. Indeed, it enabled us to build strong relationships with the shop owners, who were willing to go out of their ways to help us and respond to our curiosity. Furthermore, it enabled us to notice more, to acknowledge what seemed to be insignificant details when we only visited the store once.

However, this specific structure also forced us to face challenges. Especially, we were early on confronted to the superficiality of the semi-structured interviews we were conducting with customers. The shop is a living space but remains a transit space, which is something that is maybe even more sensible because of the narrow spatial organization of the shop. People would be willing to talk to us but would offer us five minutes of their time at most.

To offset this issue, throughout our visits, we, then, had to review our questionnaires and make them more straightforward. And, on top of the ten semi-interviews with customers and the extended one with the owner, we made use of two research methods / objects we had neglected at the start: field ethnography and the shop’s website.

To me, one main takeaway of this research project is that the researcher’s thoughts and observations are valid research material. During and after our six trips to the shop, both of us, Ning Yi and myself, would take field observation notes. We realized that these notes had an ethnographic value and were also complementary in the sense that we could confront two insider points of view regarding the atmosphere of the shop and the interactions that we witnessed.

Similarly, we broadened the scope of research material to the online website of the African Products Shop (https://africaproducts.nl/index.php). It provided us with key information regarding the products being put forward, the bestselling items and the way the shop is advertised by its owners. We attempted at developing online ethnography (Ardévol, 2012).

Our first contact with the shop occurred online and we ended up going back to these online sources.

Creating a Final Multi-Media Product to Let My Voice be Heard

Our methodology led us to identify four findings. Firstly, it appears that a tension exists between the way the owner considers his clientele and the way his actual clientele is. Then, among the Africans and African descendants that we interviewed, African consumption was:

- A cultural reminder. Most of our interviewees mentioned either their parents or their origins (be it a country or a specific ethnic group).

- A form of community support among the Black diaspora.

As for products, we noticed that hair products (gels, shampoos, extensions etc.) have a prominent place in the life of the shop, physically and online. Finally, the African Products Shop appeared as a sociability space. People would come around to have a chat, sometime not even to purchase anything.

During the research process, we collected numerous photographs, audio recordings and video clips as well as field notes. The question, then, was to find a fitting product to present the material and findings in the clearest way possible.

We first experienced with the short documentary format. We tried out two different editing software. The first one we touched upon was VUE, a phone app. This video editor was very easy to navigate and practical, because of the phone support. We could edit videos anywhere, whenever we wanted to. However, it appeared not to be flexible enough when trying to edit longer videos. For instance, we could not switch the soundtrack. So, we moved on to iMovie on Mac. It required us to get acquainted with it but after a while we were able to make our ideas come to life with it. And, we ended up with a few video drafts of 10 to 15 minutes.

However, we were struggling to find a space for our ethnographic voice as researchers to be heard in this documentary format. A voiceover could have been a solution. But we thought that it would fade and mix into the eleven other voices, which could have disturbed the audience.

That is why we, eventually, decided to mix video clips with ethnographic writing into an Adobe Spark Page story. This page enabled us to be very flexible: we could add writing, audio, video, photographs, anything we thought was fitting while still having an organized and sound product and playing on with humor by picking the most striking video clips.

Discussing with the owners, we also discovered that the whole family is involved in business activities. Their son, Bright, for instance, oversees the Mama Africa party. There is something to explore here on the role of entrepreneurship in community building (see Fitzgerald & Muske, 2016).

Going Beyond this Assignment: How it Shaped the way I think about My Own Research Project

In January, I will fly to Cape Town, South Africa, to undertake an internship at a renewable energy project development company and do research on the community response to such projects and the way it is dealt with by the company.

Thus, along this fall semester, as I was working on this research project in the Hague, I was preparing my research proposal for my own upcoming research project. And, there are three lessons I will take away with me to South Africa.

First, I have learned to be flexible throughout the research process, from the ideation to the final product creation stage. Eventually, nothing happened the way we imagined it at the very beginning of the semester. Our research object changed. Our questions were adapted. And we tried out several different final deliverable formats.

Furthermore, as I have already stated, I have understood the research value of the local scale and of the ethnographic perspective. Focusing on a specific local issue enables to bring to light much more crucial information, all the more so the researcher can adopt an ethnographic posture and notice more.

Finally, going on with the local scale, I have realized that investing time in the construction of relationships with informants is necessary. It enables to build trust and confidence, which makes both the informants and the researchers more comfortable with each other.

Three Months…

Six visits to the African Products Shop in the Hague. Ten interviews of customers. One interview of one owner. Around six hours of raw video footage. Around four hours of audio recordings. Fifty photographs. Uncountable casual interactions with customers, owners and owners’ relatives. Uncountable field observation notes. Two researchers.

All of that happened over the course of three months this semester. Three months that taught me that focusing on the local scale is a valid research starter point in social sciences and humanities and that it can enable to delve greatly deeper into the exploration of an object.

References

Ardévol E. (2012). Virtual/Visual Ethnography: Methodological Crossroads at the Intersection of Visual and Internet Research. In Pink, Advances in Visual Methods, Sage Publishing.

Audebert, C. & Ma Mung, E. (2007). Les nouveaux territoires migratoires : entre logiques globales et dynamiques entre logiques globales et dynamiques locales. Bilbao : University of Deusto, 308p.

Fitzegerald, M.A. & Muske, G. (2016). Family businesses and community development: the role of small business owners and entrepreneurs. Community Development, 47(4), pp. 412-430.

Ma Mung, E., Body-Gendrot, S. & Hodeir, C. (1992). L’expansion du commerce ethnique : Asiatiques et Maghrébins dans la région parisienne. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 8(1), pp. 39-59.

Miller, D. (2005). Une rue du nord de Londres et ses magasins : imaginaires et usages. Ethnologie françause, 35, pp. 17-26. Available online at : https://www.cairn.info/revue-ethnologie-francaise-2005-1-page-17.htm