It is with our mouths, which harbour our teeth, that we tell our stories, our histories.

Lumumba was silenced, but his tooth can continue to tell stories and histories.

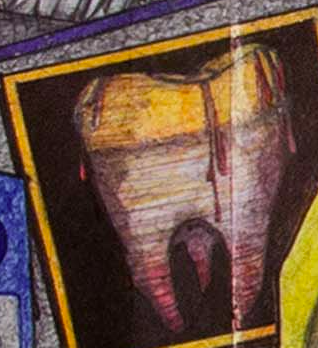

On this page, you will find information on the tooth of Lumumba, as depicted in the drawing by Sapin Makengele. In line with the course, which began with the reading of Silencing the Past by Michel-Rolph Trouillot, the choice for this project fell on: Why can the depiction of Lumumba’s tooth in Sapin’s drawing ‘The Congo Crisis’ contribute to the ‘unsilencing’ of the past? The answer to this question can be found in the video below and in the four videos that succeed it in the consecutive posts.

This first video is an introduction to the subject. It announces a number of important people and events that will help understand the videos that follow and the topic in general.

Format Choice Explained

From the start, it was evident that in the course Negotiating Power in Africa, students were allowed to think outside of the box in terms of the format their final work would be presented in. During the class sessions, we talked about different ways of sharing history, outside of the more academically conventional writing of articles. This does not mean we did not approach it conventionally at all: For each week, we read academic articles so as to gain an understanding of the context. The articles that aided in the making of this video-series are listed at the conclusion. For those interested, the books Congo, The Epic History of a People by David van Reybrouck and The Assassination of Lumumba by Ludo de Witte are highly recommended. These two books are also referred to in the video and are most helpful in understanding the greater context of the story of Lumumba. Aside from books and academic articles, however, I also made use of YouTube videos, online articles and documentaries, the full list of which can also be found on the conclusion page.

The first step towards realising other ways of sharing, has been made through this website. It does not require a person to log in and is, thus, freely accessible. Sapin’s drawing is an engaging entrance into the Congo Crisis. The different portrayals of scenes are a visual medium through which individuals can access their interests. In class, we held presentations. After I held mine on Lumumba’s tooth, it was suggested to turn it into a video, which I then decided to follow up on. Initially I considered doing something similar to a TedTalk, but after interviewing Sapin, I decided on something that would bring different sources together. This culminated into the video you can see above.

The Challenges

Making this video was new territory for me. The first challenge I faced was the interview with the artist Sapin Makengele. I had interviewed people before, but never filmed them while doing it. This interview in particular brought along some extra challenges, since I do not speak Lingala or French fluently and Sapin does not speak Dutch or English fluently. Two other students also made to interview him and the three of us had managed to find an interpreter, but the person cancelled a few days prior to the interview. Luckily, we did still find someone and were able to conduct the interviews in French. Depicted below are Sapin Makengele and Beatriz Gomez de Silva, respectively the artist and the interpreter. We interviewed Sapin in his studio, which was a wonderful backdrop. The three of us were inexperienced with videotaping, but we had received some advice on how to use it and made it work with the means we had. Notice the tripod stacked on top of the books and notebook. The quality of the film came out tremendously, in our opinions, and we were grateful for being allowed to borrow this wonderful equipment.

Once this challenge was overcome, the next step was editing the video. Luckily, one of my course mates recommended an editing programme, Filmora9, which enabled me to subtitle Sapin's words and add other videos, pictures and audio. Filmora9 provides free tutorials on YouTube, through which I managed to learn about film editing.

The third challenge that this project had to face, was that of methodology. Since the objective was not to write an article, but to make a visual research, I decided to acquaint myself with what was already available online. This is why I decided to not only use literature, but also navigate through video material. For this end YouTube was mostly, but not exclusively, used. Additionally, non-academic articles online were included. Both were used to see what had already been written on the subject. These videos and articles were watched, read, analysed and incorporated into the study. What became apparent through this search, was that there were different videos on unsilencing (even though it was not referred to under this term), on Lumumba and sometimes also on his tooth, but that there was not one video that brought all these pieces together. Forming a more complete puzzle out of these pieces is what this documentary hopes to achieve. The videos were selected on the mention of Lumumba, on the mention of Lumumba’s tooth and on the contribution or demonstration of unsilencing. When seeing the video, one sees that this unsilencing has been categorised into three themes. A thematic approach was chosen as it highlighted the story of unsilencing. The three themes are: 'The Unsilencing of Bloodshed', 'The Unsilencing of What Happened to the Tooth' and 'The Unsilencing of History that is Confronting'. Lumumba’s tooth could function as a more symbolic feature, as demonstrated in the first and last themes, or a literal one, as shown in the middle section.

Based on personal experiences, the students in the class agreed that it is more likely that their friends would watch a YouTube video they sent than read an article they shared. This was one of the contributing factors in the choice to step away from the academic article format and make something that was more easily accessible to a wider audience. As historians we study the past, yet we must be careful not to stay in it too much ourselves. This is not to say we should discard articles or books, but rather that we should be open to including other ways of discovering history. A YouTube video can be as well backed and embedded in literature as an academic paper, but it is likely to reach a wider audience. Once an initial interest is sparked, it seems people would be more likely to look around and discover more about formerly silenced subjects. Additionally, as YouTube is free for all users, it also allows for history to be more accessible.

Video and audio may also be seen as more inclusive tools, since they allow people who have difficulty reading or seeing to engage more with the material. Here I want to emphasise I do not think conventional methods such as the writing of articles should be replaced, but rather that different sources and methods should be included. A painting, for instance, can spike curiosity and motivate an individual or group to discover more about a piece of history. An image can evoke an immediate emotion which can then spur the person on to investigating further through text, audio or film. Inclusivity aids accessibility and this accessibility is vital in unsilencing.