Research project by Chiara Cozzatella & Pieter Roden

This research project aimed at understanding how the recent Tigrayan conflict was portrayed via TikTok. TikTok is a social media network primarily based on short videos, where the audiovisual dimension is essential. This element and the fact that young people mainly use TikTok make it an interesting platform to look at for discourse analysis. Despite this, it has so far received little academic attention. Therefore, it seemed fascinating to understand the narration of a conflict such as the Tigrayan one on this platform.

Abbink (2021a, 2021b) identified that the Tigrayan war is marked by bias, incompleteness, lack of context understanding, credulity and an anti-federal goverment attitude amongst mainstream media sources. Abbink suggests this is fueled by widespread disinformation around the war on a number of social media platforms. We sought to extend Abbink's investigation into TikTok as a newly emerging social media platform, recognising the platform's general lack of academic engagement. to explore whether similar biases are present on the platform.

We started our research by gathering information on the context of the war and the conflict itself. Our first sections of this blog demonstrate this context and the context of TikTok in Tigray, and their relation to wider informational technologies, such as the distribution of mobile phones and social media in Ethiopia. In this way, we have created our background and shaped our analysis, on the basis of our findings. We analyzed TikTok videos, to answer our main research question: how are discourses of ethnonationalism spread through Tigrayan diaspora TikTok-ers in the wake of the Tigrayan War?

Our Research

We conducted the research between November and December 2022. We created two TikTok profiles and started following some popular profiles which were publishing content on Tigray or the conflict. In this way, we trained our algorithms. After a month of research, we looked at the main narratives. We focused on video and audio together with hashtags and texts to explore which kind of narrative was presented or promoted on Tigray and the conflict. We placed these narratives within the academic and media information we accessed on Ethiopia, Tigray, and the Tigrayan conflict. Overall, we found a general lack of knowledge and understanding of the war, which is also claimed by scholars (Abbink, 2021a). This is also demonstrated by internal debates within international organizations such as the UN (ibid.). We noticed an outstanding need for information from Tigray caused by general electricity and connection shortage, together with issues related to the distribution of mobile phones with mobile data.

Considering the dimensions of this project, we focused our final analysis on three diverse TikToks. To broaden our approach and limit the imposition of our own interpretation, we have looked at the reception of these by including a word map of the top 100 comments on each of them. We have found that TikTok mainly shapes ethnonationalist discourses through its multi-media format, incorporating distinctly pro-Tigrayan visual imagery and music. At the same time, the narrative on the Tigrayan conflict largely remains a youth diasporan phenomenon at the moment. To summarize, we have decided to observe the outstanding narratives, follow the most popular hashtags and videos, and highlight the chosen narrations.

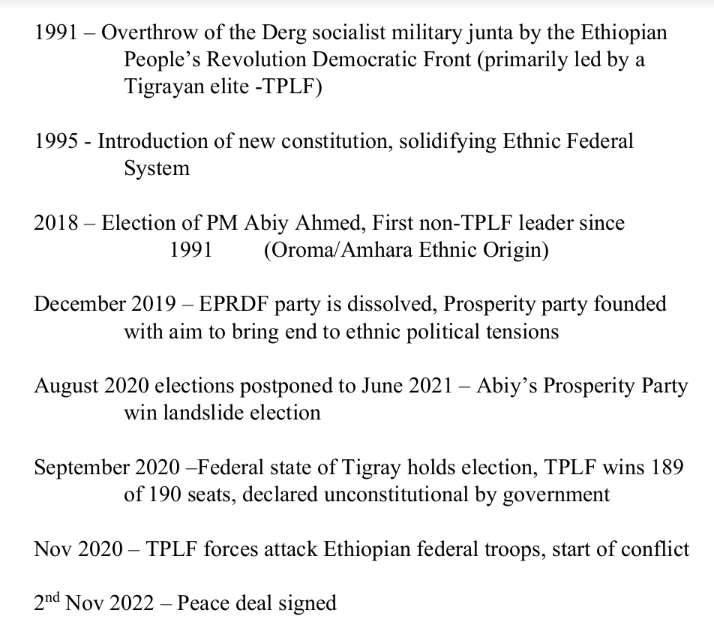

The Tigrayan conflict

Ethiopia runs through an ethnic federal constitution where the 11 Ethiopian regions are all allowed high levels of autonomous rule, Tigray is one such region. The Tigray conflict erupted in November 2020 when the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), a political party previously in power from 1991 through to 2018, launched an attack on a significant Ethiopian government military base. This attack came after an escalation of long-running tensions with the Tigray region holding its own elections after the government postponed elections amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The current Ethiopian government, led by PM Abiy Ahmed, is the first government to be led by a non-Tigrayan since the TPLF overthrew the Derg Military Junta in 1991. In November 2022 the government and Tigrayan forces came to agree on a peace deal which has allowed a fragile level of peace to return to the region.

Contextualising mobile phones and internet use in Ethiopia

(Connecting Africa, 2021)

Digital connectivity is on the rise in Ethiopia but access to internet and use of social media remains limited. The majority of social media users are located in more urban areas, largely in the capital Addis Adaba. In rural areas, mobile phone use is significant, but access to stable electricity or internet is rare. Rural mobile phone users therefore often depend on older models of phone with long battery lives. These may be charged every few weeks in small towns or villages with stable electricity connections, these charging points are also points of exchange - video, image and audio files may be exchanged via bluetooth connections.

'Adey' and the Soloda Mountain: #tigraytiktok

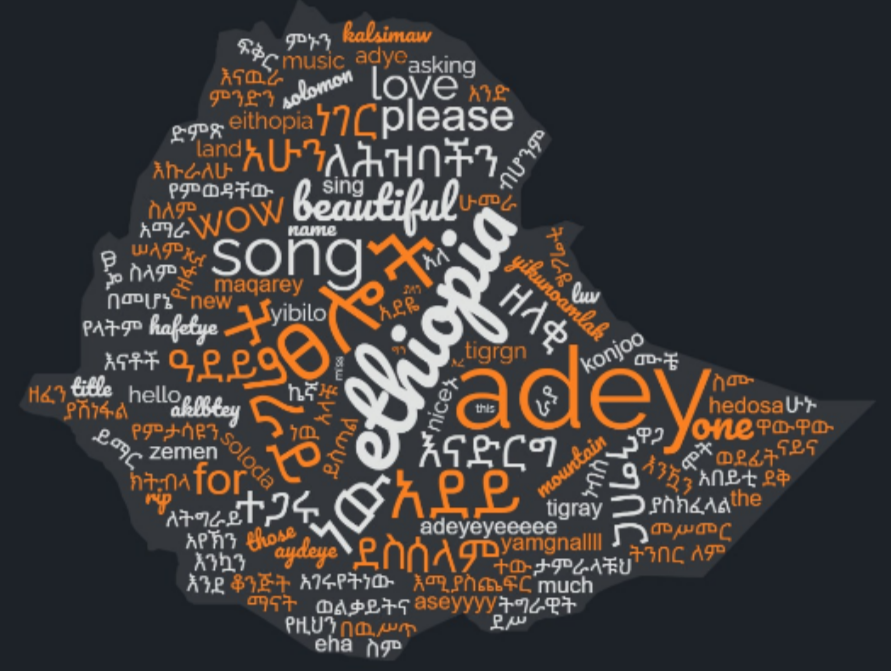

It is interesting to highlight several elements to understand and frame the discourse of this TikTok video. Firstly, it was published on the day before the peace deal ratification between the parties on November 2nd, 2022. While the profile itself is called “PrayForTigray”, the hashtags used seem to refer to an Ethiopian audience to some extent. A pro-Tigrayan stance is taken with the #tigraywillprevail. Tigrayans, or Ethiopians in general, are recalled through the #Tigray_ትግራይ (Tigray in Amharic). This video is filmed in the foreground of Soloda Mountain, close to Adwa (a significant location for Ethiopia for its victory against the Italians in 1896). What is interesting visually is that the two characters in the TikTok video are moving around, dancing, smiling, and pointing at the mountain. The song, Zemen Yibilo, by the Tigrayan artist Solomon Yikunoamlak, repeats the word “Adey” in Amharic means “Ethiopian daisy”: it is certainly interesting to look at the correlation and the will of representing Tigray as the Ethiopian daisy on the background of Tigrayan music.

Quick facts about this TikTok video: 962K views, uses #tigraytiktok, a hashtag with 1.9 billion views. Other hashtag used: #tigray #tigraytiktok #tigraywillprevail #tigraymusic #Tigray_ትግራይ

ለትግራይ እናቶች ድምጽ ሁኑ አሁን እሚያስጨፍር ነገር አለ ('Be a voice for the mothers of Tigray')

ዉሾች 😡 ('Dogs')

Here is a word map with the top 100 comments on the TikTok video above, referred to as ‘Adey and the Soloda Mountain’. Two elements stand out at first sight: there are words written both in Latin and the Amharic alphabet and there are words in Amharic and English. This shows the interaction created by the hashtags, which refer to Tigray specifically. While a lot of comments refer to the music in the background of the video, many others refer specifically to Tigray, recalling the name ‘Adey’ and referring to the region as beautiful and expressing a sense of belonging.

mariyamen am Happy for you my people

የኢትዮጵያ ጠላቶች ('Ethiopia's enemies')

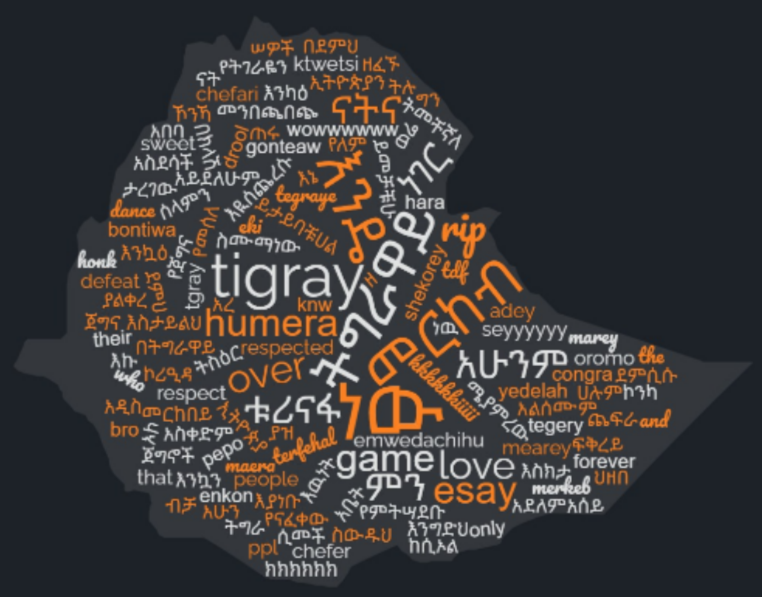

Music and #tigraywillprevail

This TikTok video is particularly interesting since the main character, Merkeb Bonitua is a Tigrayan hip-hop artist active in the region and its politics. The setting of the video immediately captures the attention: in a recording studio, Merkeb Bonitua is wearing the military hat of the Tigrayan Defence Forces (TDF). He dances during the whole video, and lastly, does the military salute pointing at the cap. In the video also appears a second character, dancing with Merkeb Bonitua while playing the krar. This character also wears a red hat that does not have the Tigrayan yellow star. For what concerns the music in the background, the song is Ati Hidegini, from Geza Tigray. The perspective taken in this TikTok video is clear: the hashtag #tigraywillprevail stands out, contextualizing the video in the Tigrayan TikToks (#tigraytiktok, #Tigray_ትግራይ).

Quick facts about the TikTok video: it has 218.5K views and uses #tigraywillprevail, a hashtag with 220 million views. Other hashtags used: #merkebbonitua, #hellog, #tigraytiktok, #Tigray_ትግራይ,,tigrayadey,#viral, #fyp, #follow.

ሀሉም ነገር እኩ በትግራዋይ ነው ሜያምረው 🥰🥰🥰 ('Everything is beautiful in Tigray')

ምድረ ለማኝ ሁሉ ከጠፋችሁበትተ ጉድጓድ ወጣችሁ አይጦች ናችሁ ('You are mice out of the pit where all the beggars are lost')

This is a word map of the top 100 comments in the TikTok video above, which we have called ‘Music and #tigraywillprevail’. Again, it is immediately evident that both English and Amharic words are used in the comments, which brings this TikTok to an Ethiopian and Tigrayan audience. Many comments refer to Tigray itself as the Adey, showing affection, affiliation, and respect for Merkeb Bonitua. Nevertheless, opponents’ comments are also noticeable: the word defeat appears together with a derisive “game over” and “rip Tigray”.

the only ppl who I knw that dance on their defeat😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂😂

tdf forever🥰🥰

Spreading information on the conflict: #Tigraygenocide

The tone and modalities of this third TikTok video are entirely different from the ones above. The main character speaks directly to the camera in an involved and slightly aggressive, informative tone. This element and the fact that everything she says is subtitled are impressively interesting in this video. She is mainly addressing the non-Ethiopian world, identifying herself as a Tigrayan diasporan. She proceeds in the video contextualizing the beginning of the conflict in Tigray “around the same time as the United States presidential elections”. She talks about the war, attacks the Ethiopian government, and stresses the crisis inside the region. It is interesting to notice the changes in the narrative used here: relevant confidence in front of the camera is shown, while a moment of broken voice is included when talking about starvation in the region. The TikTok video concluded with a request to make the hashtags #Tigraygenocide and #stopwarontigray viral. This particular element is quite interesting since it shows the perspective adopted on the conflict: the war is being referred to as on Tigray, implying subjugation and passiveness of Tigray. Indeed, the first hashtag used is #tigraygenocide, which Abbink's (2021b, p.4) research shows is "a meme recklessly used and repeated

time and again but incorrect in the juridical and actual sense". Launched in the first 24 hours of the conflict to influence media and policy campaigns amongst the West (ibid.). A relevant element to mention here is that this user, together with a group of Tigrayan diasporan tiktokers, has realized a movement, #RestoreMotherland, to raise funding for the education of children in Tigray.

Quick facts about the TikTok video: it has 64.7K views (it is essential to highlight that the profile has videos with more views, one with 701K). It uses the hashtag #Tigraygenocide which has 32 million views, together with the hashtags #stopwarontigray, #blacklivesmatter, #Christian, #muslim, #Africa, #trending, #Tigray, #ethiopiantiktok, #africantiktok.

what can we do to help

Why am I just hearing about this

Here is the word map of the top 100 comments of the third TikTok video presented, referred to as ‘Spreading information on the conflict: #Tigraygenocide’. What is evident in this case is that there are only words in English. Some interesting frequent words are ‘boost’, ‘know’, and ‘yellow’, together with the figuration of a frog. Many comments on the video refer to not knowing anything about the conflict. At the same time, several random comments, such as the emoji of a frog, were posted to boost the video on TikTok. Many words seem random or out of context: the will to spread the voice seems well received and realized. These comments in comparison to other TikToks are therefore explicitly aimed at increasing the virality of the TikTok, spreading its influence by engineered commenting which is more likely to spread the TikTok's influence. The two previous comments sections can be seen to be more representative of an audience actually interacting with the content of the TikTok itself.

#tigraygenocide what’s y’all’s favorite pizza topping?????!?!!?

BOOST: what’s y’all’s favorite color? Mines yellow

Findings and analysis

- Tigrayan TIkTok relates largely to diaspora communities with greater access to social media and communication technologies

- Narratives are largely one-sided Pro-Tigray expressed through visual imagery which includes the Tigrayan star, soldiers uniforms and idyllic Tigrayan landscapes, as well as music and sound which propogates Tigrayan patriotism and a strong individual identification with Tigrayan people and the region

- Hashtags such as #TigrayWillPrevail, #StopWaronTigray and #TigrayGenocide place Tigray into an underdog position, casting all responsibility for the war onto the Ethiopian government

- This follows the ethno-nationalist trends identified by Abbink (2021a, 2021b) around digital media narratives and misinformation on Tigray, including the (juridicially incorrect) claim of a Tigrayan genocide

- The TikToks attract different audiences dependent on the audio-visual semiotics and hashtags used as can be identified by the varied language in the different comments sections.

Conclusion

Through our study we found TikTok to be a multilayered and structured form of communication. This, together with a general lack of academic work on TikTok and its uses, was already a compelling reason for us to start a research project on the social media app. A groundbreaking element is, of course, tied to the fact that TikTok has a low entry barrier, making it easy for a wide range of users, primarily young people. This makes TikTok a platform where youth can share all kinds of content in many ways, even though the app is trying to handle hate speech and misinformation (Anderson, 2020). Overall, TikTok is a platform where young people speak up and create dialogues and communities. This space allows the creation of many different discourses, from light and funny things, to share and connect to important and serious matters that need to be spread online. Therefore, a more accurate and specific branch of research should be realized on TikTok, and we thought it was an interesting point to start from in a small project such as ours.

References

Abbink, J. (2021a) The Atlantic Community mistake on Ethiopia: counter-productive statements and data-poor policy of the EU and the USA on the Tigray conflict. ASC Working Paper, 150 (2), pp.1-30.

Abbink, J. (2021b) The politics of conflict in Northern Ethiopia, 2020-2021: a study of war-making, media bias and policy struggle. ASC Working Paper Series. 152, pp.1-24.

Anderson, K. E. (2020). Getting acquainted with social networks and apps: it is time to talk about TikTok. Library Hi Tech News, 37 (4), pp.7-12.

Connecting Africa (2021) Connectivity: Only 20% of Ethiopians are online. [Online] Accessed via: https://www.connectingafrica.com/author.asp?section_id=761&doc_id=768066 [10/01/2023].