Discourse Analysis of the Black Manifesto

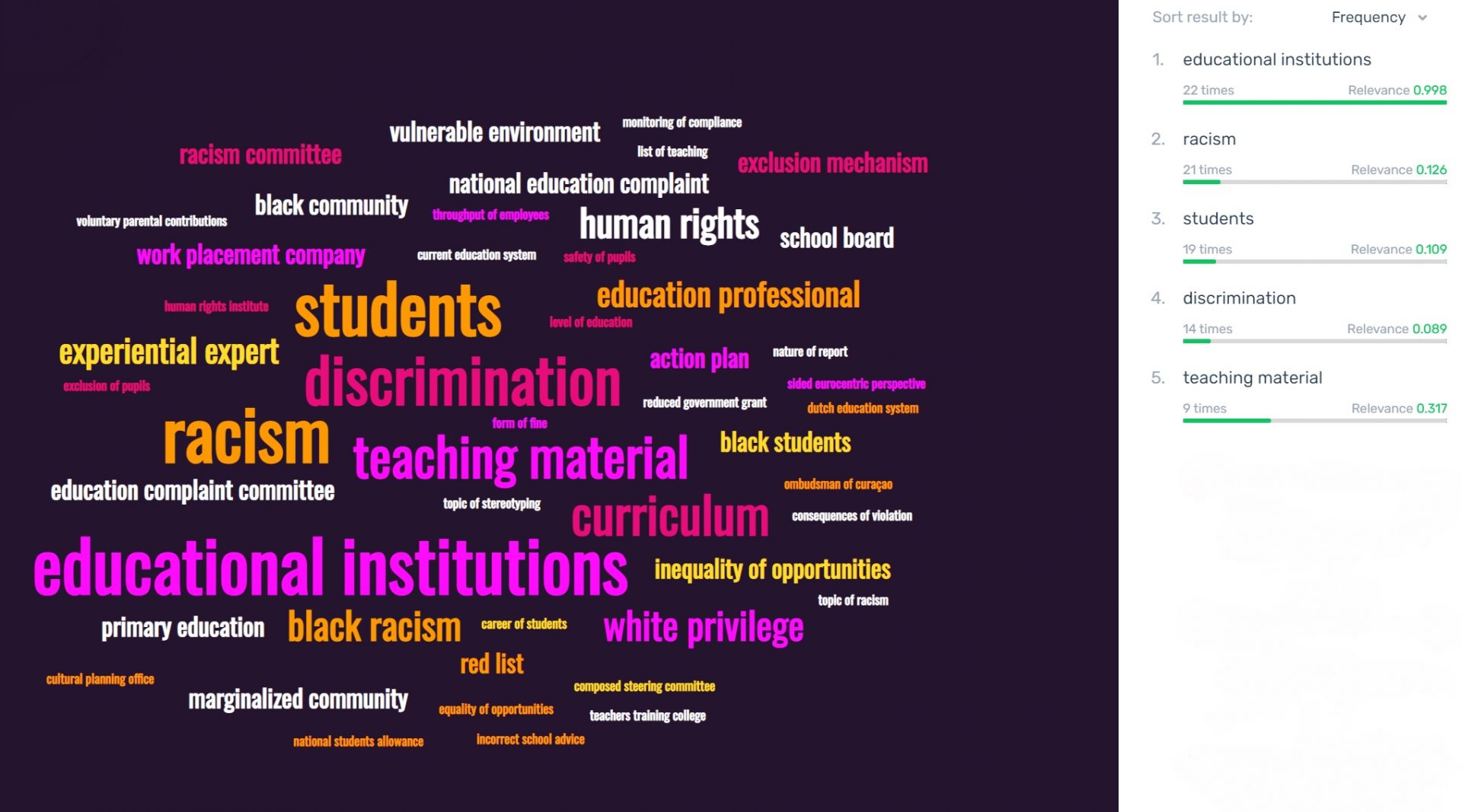

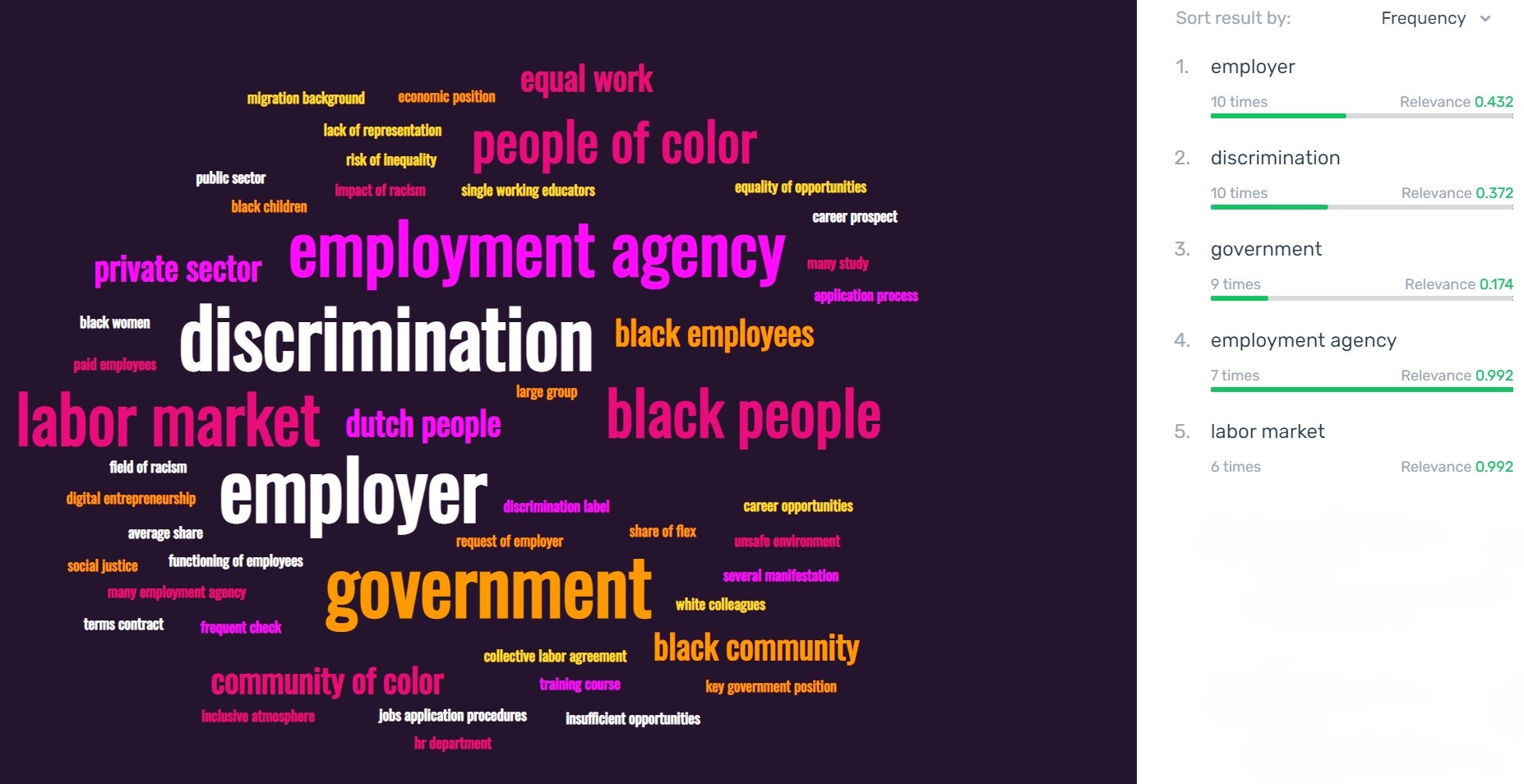

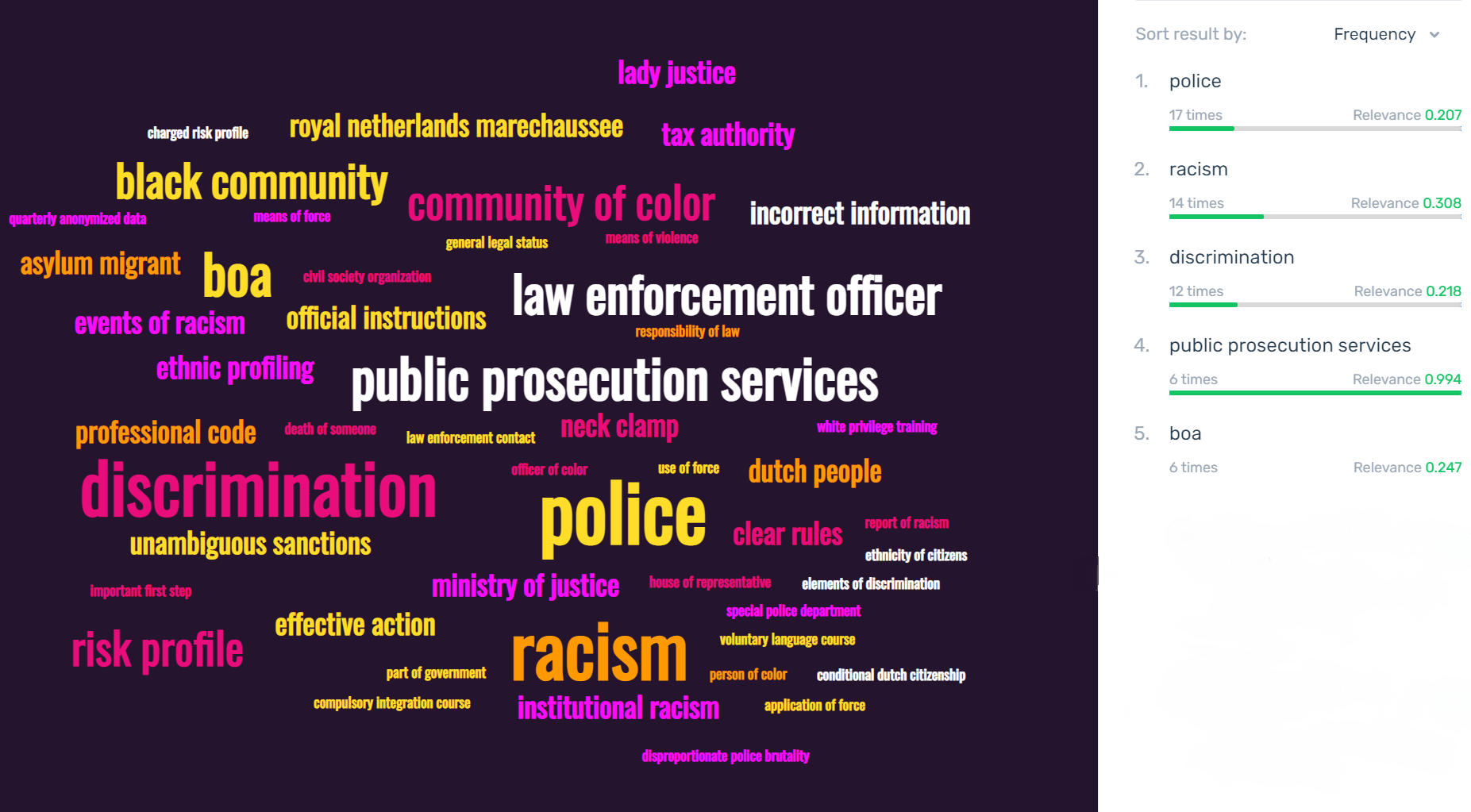

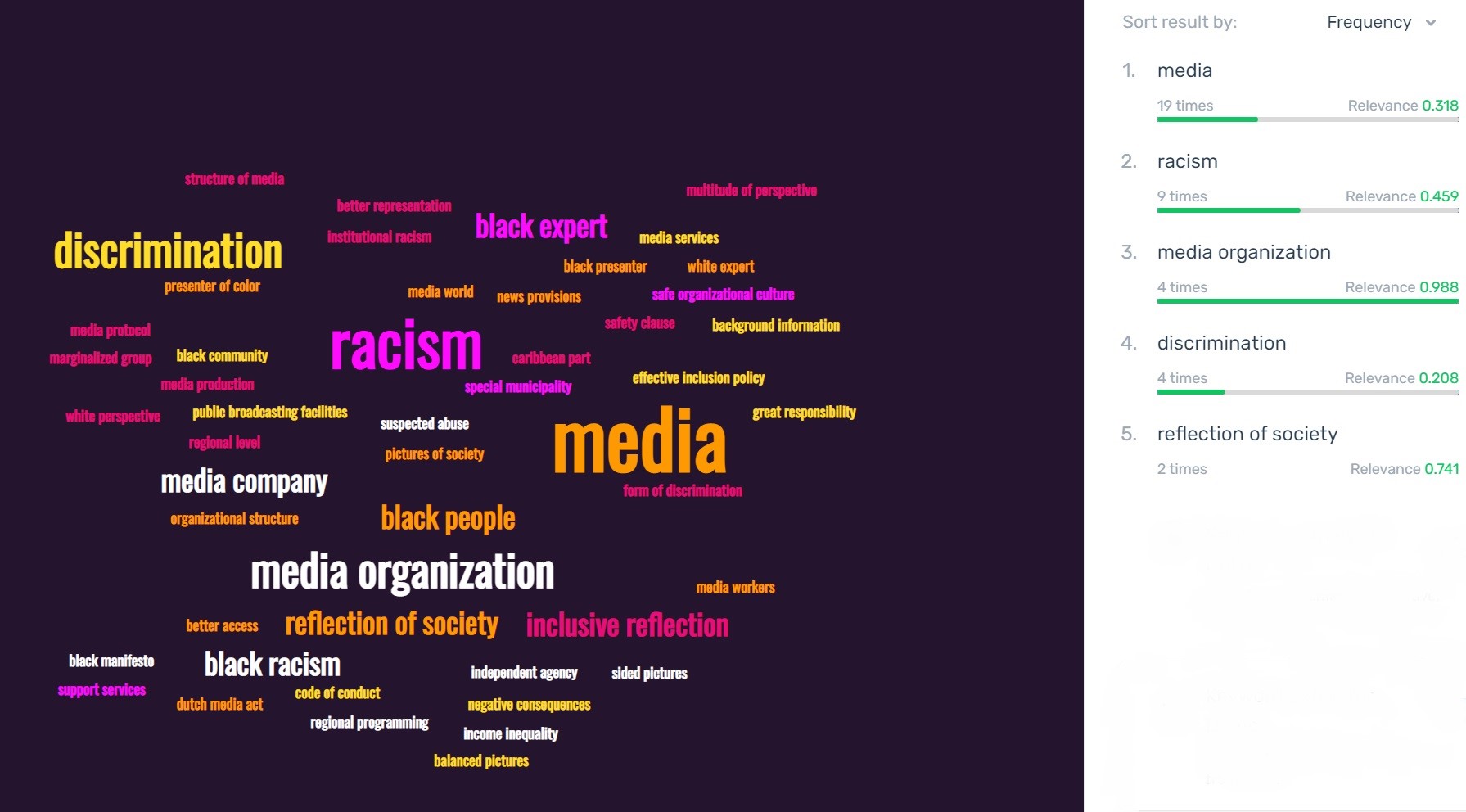

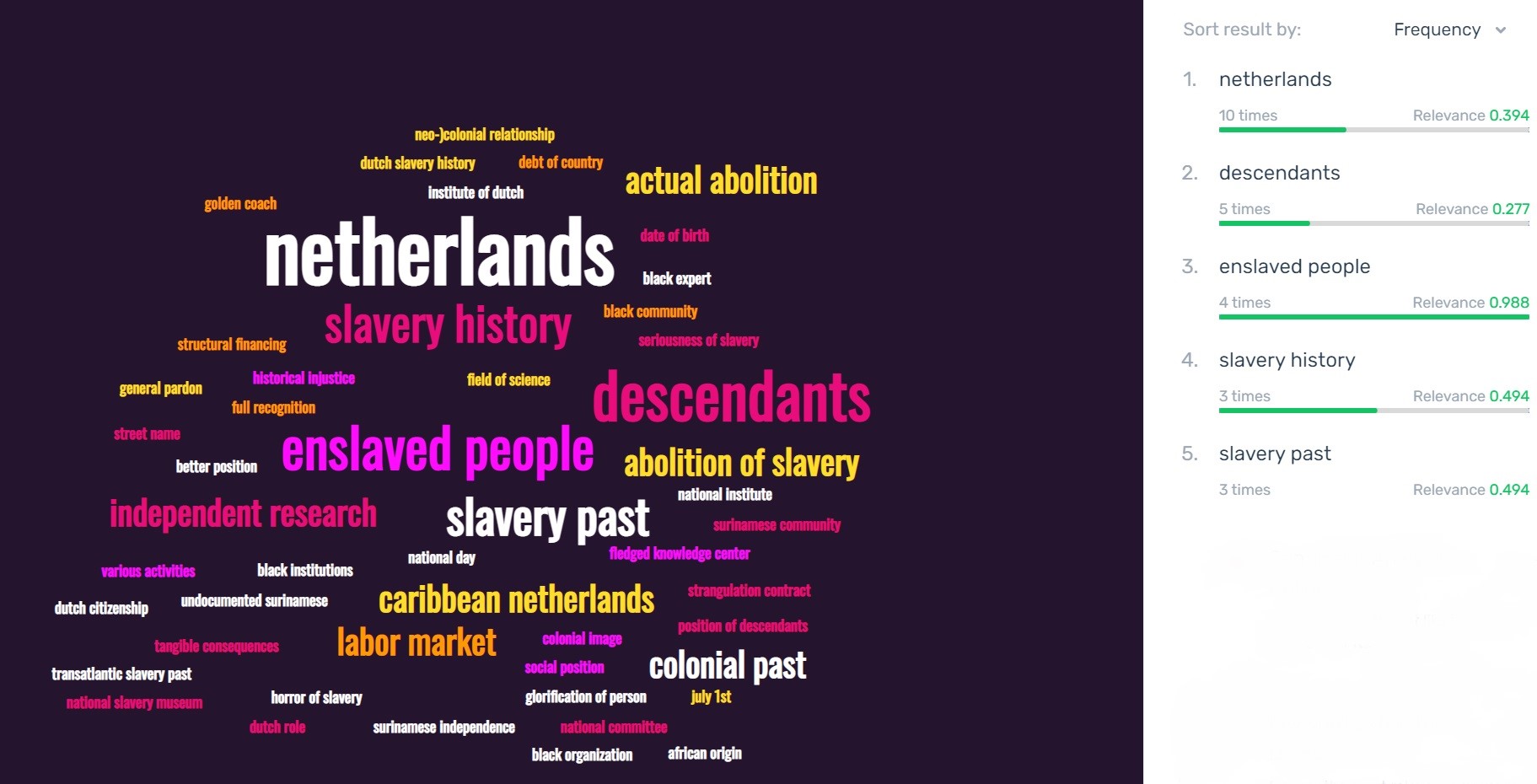

Apart from our written findings, underneath each domain you find the word cloud that we created per section, based on the text of the Black Manifesto. These word clouds allow you to see the frequency of certain words used throughout each domain, and therefore what words mostly stand out.

Domain 1: Education

The Manifesto opens this first domain with a strong affirmation: “The current education system promotes inequality and therefore needs to be thoroughly overhauled.” It is clear that according to the Manifesto, educational institutions are unequal, and that students from non-Western backgrounds and from socio-economically vulnerable environments are disadvantaged. By stating that “decolonization must take place throughout the Dutch education system” and that “Black (LHBTQIA+) history must be included in the curricula,” it is highlighted that the Dutch education system is not yet fully decolonized, and that black history is not included in the school curriculum. This can be seen as a source of exclusion. Indeed, the Manifesto also states that “Every educational institution should have an inclusive integrity policy with topics such as security and exclusion mechanisms,” highlighting how at the moment such inclusive integrity policy is not adopted by the Dutch educational institutions. Moreover, there are some practices that according to the Manifesto can lead to exclusion of vulnerable children. In particular, the manifesto states that the voluntary parental contribution that parents provide the school with is voluntary only in name and contributes to the exclusion of socio-economically vulnerable children from extra curricular activities. Children won’t be excluded if the voluntary contribution is abolished, and if there are consequences for excluding children. In addition, the Manifesto highlights that at the moment, there are no national allowances that schools can use to help students in socio-economically vulnerable situations and allow them to participate in those activities that require additional contribution. Hence, this further exacerbates exclusion of children.

The Manifesto also highlights that there is no mechanism in place that would facilitate the reporting of the use “of discriminatory, stereotyping or racist image and/or text use in the teaching material,” and that therefore an anti-racism committee must be set up, and “educational institutions that are guilty of racism and discrimination must face serious consequences.” For what concerns the teaching material, the Manifesto highlights that it is still very Eurocentric, and that the Dutch past is not properly faced. The Manifesto states:

“The slavery past and how it affects it, colonialism, the migration past, white privilege and the division of the Dutch Kingdom must be given a structural place in the curriculum. To combat racism and exclusion, students must have knowledge of, among other things, the different places, languages, flags, national symbols and cultures within the Kingdom. Students should familiarize themselves with the 'Statute for the Kingdom of the Netherlands' and learn how slavery and inequality permeate as structures within the Kingdom. Educational institutions organize excursions to museums and other cultural institutions with exhibitions and activities of Black and other 'non-Western' cultures, civilizations and traditions. Educational institutions also offer activities related to racism and discrimination in their program. The topics of racism and discrimination should be a mandatory part of the curriculum of educational institution”

This highlights that topics of racism and discrimination are not really and properly dealt with at the educational level. This means that indeed the educational system is not decolonized, in the sense that children do not learn about different places, languages, flags and cultures of those countries that constitute the Kingdom of the Netherlands. They do not learn how slavery and inequality permeate the Kingdom’s structures, therefore further increasing such inequalities. There is no mandatory class on racism and discrimination, which according to the Manifesto instead should be taught at school, starting from primary class, with the exact aim of fighting their spreading. Nevertheless, the Manifesto states that “the curriculum of pedagogical academies and teacher training colleges should include teaching material on inclusion, intersectionality, white privilege and anti-prejudice.” This means that teachers themselves are not equipped with tools that would allow them to properly talk about topics such as discrimination and inequality and racism. The Manifesto concludes stating that the problem is not only visible at the primary school level, but also at the academic level, as it states that “educational institutions should offer study programs that deal with Afro-Dutch history, the transatlantic slavery history and Dutch colonial history. These specializations should also be created for Bachelors, Masters and postgraduate students.”

In the education sector, the words most used are: “Educational institutions” (22 times), “Racism” (21 times), “Students” (19 times), and “Discrimination” (14 times). Educational institutions and students are the subject of these sections. However, the frequency of the words “racism” and “discrimination” highlights the two main problems that according to the Manifesto permeates the Dutch school system.

Domain 2: Health and welfare

When it comes to the second domain of the Manifesto, the harmful impact of racism and discrimination on the mental and physical wellbeing of Black people and people of color is mentioned, as well as the daily stress, threats and violence these people face. Yet, the evidence on which this argument is based stems from findings of a study conducted in the US, and does therefore not directly depict the Dutch health and welfare system. The Manifesto however does speak of a dominant Western diagnostic system that creates a situation in which white skin color is the norm, both for patients and for health care workers. This description implies that such a diagnostic system is also at place in the Netherlands.

Suggestions made for the health and welfare sector in the Netherlands mostly point to the need of doing research on the position of Black people in health care. Indeed, “(er moet) onderzoek komen naar” (translated into: “research (needs to be) conducted on”) is among the top five of the word frequency list (see below). Apart from the need for research, the other suggestions put forward by the Manifesto mainly highlight that in general, prejudices and stereotypes by health care professionals and institutions are still in place in the Dutch health care sector, and lead to wrong diagnoses and the underestimation or even ignorance of complaints. Besides, the sector is not accessible for Black, undocumented refugees, mainly due to the fact that the Dutch language currently functions as an instrument for exclusion within care and wellbeing. Because of policy and budget cuts, interpreters are no longer available. Furthermore, because of language problems, Black people are less informed about the Dutch health care system.

The policy measures that the Manifesto states to improve the current practices of the Dutch health care system highlight the need for intercultural management in every line of business, “to optimize intercultural awareness and better align practices to different persons with health care needs.” This implies that currently, the Dutch health care sector lacks such intercultural awareness. The Manifesto furthermore states that people should not be viewed in isolation from their cultural context, and that in all aspects, health care approaches should be intercultural and affordable to the marginalized group that many Black health care users and health care users of color are part of. Dutch insurance companies also play a role here, as they currently restrict the freedom of choosing health care by Black health care professionals and this care is not part of the standard health care package. Besides, currently patients are able to refuse the help of Black health care providers, which should also be prevented according to the Manifesto. The Dutch health care sector could further improve on its level of interculturality, through the suggested implementation of “obligated sensitivity trainings with respect to LHBTQIA+, anti-racism, anti-prejudices, anti-sexism, and anti-vandalism” by the Manifesto. The Manifesto furthermore states that within the organization of health care, diversity deserves more recognition, as Dutch health care employees are currently not sufficiently representing their patient population. As the Manifesto straightforwardly states: “The 1.42 million health care employees and managers should strive towards being inclusive, socially just, and anti-racist”. The fact that the Manifesto also calls for the abandonment of terms such as ‘negro race’ in guidelines implies the presence of racial theories and terminology in health care practices.

Thus, when it comes to the health and welfare domain in the Netherlands, several characteristics can be attributed to the Dutch system based on the text of the Manifesto. What mainly stands out is the emphasis placed upon interculturality and intercultural awareness. The Manifesto highlights several aspects of the health care system that are all part of the ‘dominant Western diagnostic system’ that Dutch society is placed in, and in which white skin color remains the norm. The Dutch health care sector lacks intercultural awareness in a variety of domains according to the Manifesto, and black people and people of color face exclusion due to prejudices and stereotypes by both patients, professionals and institutions, a lack of interpreters available, practices by insurance companies such as the covering of diseases that are mostly appearing among black people or people of color, and uneven support for black informal care takers. The manifesto argues for a quota system that allows for a socially just representation of employees, and for the implementation of an inclusive and representative curriculum for students. This implies that both measurements are currently not in place in Dutch society.

Domain 3: Housing

When it comes to housing, the third domain of the Manifesto, the text opens with a strong sentence: “Housing is a basic right for everyone in the Netherlands. At least it should be.” This immediately highlights that some people are excluded from the right to have a house. The Manifesto then continues stating what a “just” Dutch society would look like, implying therefore that there are some injustices according to it:

“A just society provides sufficient affordable housing, shelter for refugees (without documents) and housing for people who, due to whatever circumstances, do not have a safe home. A just Kingdom does not accept racism and discrimination in the housing market. A just Netherlands ensures that all its residents have a roof over their heads. A just Netherlands recognizes that asylum seekers, illegalized refugees and other undocumented migrants who have exhausted all legal remedies are also entitled to shelter.”

Moreover, the Manifesto states that at the moment racism and other forms of discrimination in the housing market are not sufficiently (or at all) punished. In addition, those who do not speak Dutch are not assisted by the government to find a house or shelter, and that there is no system in place to protect them from exclusion because of the language.

For what concerns people of colour, the Manifesto states:

-

Access to (homeless) shelters should be full and equal for LGBTQIA+ people, especially Black transgender women and women who are victims of domestic violence or intimate partner violence.

-

Safe asylum seekers centers must be established for Black LGBTQIA+ migrants

-

Black youth should have an equal opportunity for youth and student housing.

The use of the verb “should be” or “must be” underlies that those conditions are not met at the moment, calling for the necessity to close these gaps to ensure that these people are properly protected and can enjoy the same rights that are ensured for other categories.

Domain 4: The labour market

When it comes to the fourth domain, the labour market, the Manifesto states that discrimination forms a structural problem that has consequences for Black people, as it hits both their social-economic position, and their wellbeing. The Manifesto also points to the multiple dimensions of the problem: Black people (and mainly black women) earn less than their white colleagues, there is discrimination within job application procedures, and many employment agencies are willing to discriminate if employers request them to do so. Besides, black people more often face racist jokes from colleagues and other microaggressions that create an unsafe working environment, and their chances for career opportunities are limited.

According to the Manifesto, the Dutch government has a responsibility in setting the right example for countering labour discrimination. Among others, “The government should enable equal chances at the labour market to counter labour discimination”, which means that currently, such measurements are not at place in the Netherlands. What furthermore stems from the Manifesto is that there are currently no consequences based on criminal or administrative law after racism and discrimination by employers and employment agencies in the Netherlands. This creates an environment of the Dutch labour market that is depicted as not safe, not inclusive, and not reachable to everyone.

When it comes to representation, the Manifesto again points to the government, stating that: “Government instances should enable career opportunities for Black people and people of color. These groups are currently underrepresented when it comes to key positions within the government”. Using quota is suggested as a way of tackling the uneven representation in the public and private sector, as well as embedding inclusivity in hiring- and application procedures and enabling equal opportunities for career perspectives.

All in all, from the way the Manifesto describes the current situation of the Dutch labour market, it becomes clear that this domain in the Netherlands creates an uneven environment for Black people and people of color. This group often faces racism and discrimination at the work place and is limited in pursuing career opportunities. Besides, Black people and people of color have flex contracts or contracts for specific periods, and inclusivity is lacking in current hiring- and application procedures by employers and employment agencies.

Domain 5: Economic equality

The title of the fifth domain, “economic equality”, already tells us that actions still need to be taken to reach equality in the economic sector, which is not currently present. This section is particularly interesting because the Black Manifesto does not advocate only for people from the Black community, but it talks in the name of everyone who has a low socio-economic status. Indeed, the Manifesto is advocating important changes in society as a whole, for economic equality for everyone. For example, the Manifesto states that: “Childcare should be free for single working educators and households with an income below the average. Childcare must become part of the employment contract.” This means on the one hand that there is not a policy that helps single working educators with an income below the average to face the costs of childcare. On the other hand, the Manifesto does not say that such policy should be applied only to certain categories, hence it is advocating in the name of all those people whose income is below the average.

However, the Manifesto highlights that “people with a low SES more often have problematic debts, experience poverty and health problems more often and live on average six years shorter and fifteen years in poorer health.” And because of “structural inequality, the impact of the colonial past and institutional racism in society, Black people are overrepresented in these figures.” Hence, the colonial past and institutional racism deny some people the possibility to be fully included in the society. Moreover, the Manifesto underlines that the problem is rooted also in politics, as the government itself sometimes brands “Black people and people of color as fraudsters.” In addition, the government does not provide “adequate” help for “people who have a lower command of Dutch,” resulting in a dichotomy in Dutch society, in which “certain groups systematically experience unequal treatment.”

The Manifesto also states that there are no administrative or criminal consequences when racist or discriminatory acts are carried out, for example when people don’t provide a rental home, mortgages or loans.

Overall, what the Manifesto in this section highlights is that economic equality should be improved in society as a whole. The Manifesto is working to improve Black economic equality, but this provision would also benefit those who are not Black, rendering society indeed more equal.

Domain 6: Politics and governance

When it comes to the sixth domain of politics and governance, the Manifesto starts with the general statement that governments, companies, instances and NGOs need to act according to human rights declarations and guidelines at all sectors of their (inter)national relations and in their political and economic policy approach. The criminalization and deportation of Black migrants and other migrants from communities of color should end, as well as the noncommittalness of measurements against anti-Black racism, islamophobia, anti-semitism, LHBTQIA+ hate, and other forms of discrimination. In the Manifesto, Dutch politics are depicted as not explicitly mentioning and fighting anti-Black racism. Since the government represents the entire Dutch population, the government should set the right example by reflecting the broad diversity in society in its councils, the parliament, and at all other levels. This statement implies that currently, the Dutch government lacks the diversity and representativeness necessary according to the Manifesto. This also means that the government should not cooperate with parties that are guilty of punishable facts such as racism and discrimination.

The Manifesto comes up with several action points for the politics and governance sector, that mainly highlight the need for a national approach to fighting institutional racism and discrimination, under direction of the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. The Ministry would be responsible for setting up a national office for discrimination and racism, which also requires a special States Committee for discrimination and racism. According to the Manifesto, this would foster the national awareness that is needed to fight and prevent institutional racism in the Netherlands, but that is currently not at place in Dutch society. An important aspect of this suggestion is the hiring of black societal organizations and black experts, to account for the diversity and representation mentioned above. Such black experts should, among others, assist in independent research on institutional racism at the national, regional and local government.

The Manifesto furthermore pleads for an anti-discrimination behavioural code that encompasses plans for prevention and education of racism and discrimination, as well as for the implementation of an anti-discrimination contract for the Dutch government. In case of violation, measurements applicable to the situation should be taken, including criminal prosecution.

The Manifesto also devotes a section to stereotyping, hereby mainly focusing on the illustration of Black Pete in children’s books and the abandonment of such books, as they are currently still available. The Manifesto wants the Dutch parliament to explicitly recognize that Black Pete is racist, and that mayors should not be present if the arrival of Sinterklaas is accompanied by Black Pete’s or other forms of stereotypes. Otherwise, this is a legitimization of racism.

Finally, with regards to international relations, the Manifesto states that foreign policy between the Dutch government and its partners should be evaluated on institutional racism and discrimination. NGOs and foundations are also mentioned here, as they do not always seem to be anti-racist in their expressions or in the material they use for recruitment and sponsoring. Besides, the fact that the Manifesto demands that: “Expertise and experience of local organizations should be respected by NGOs and foundations operating in non-Western countries” indicates that this respect is currently not at place.

All in all, when it comes to politics and governance, the Manifesto mentions a variety of sectors that need restructuring, ranging from the Dutch parliament to NGOs. Institutional racism is mentioned several times in this domain. According to the Manifesto, this institutional racism is still deeply structured in Dutch governance, both for domestic and foreign political policies. With specific anti-discrimination behavioural codes the Manifesto wants to tackle this.

Domain 7: Justice and security

In the seventh domain of justice and security, the Manifesto underlines that justice is considered to be blind, but that “this is not the case in practice.” Indeed, according to the Black Manifesto some characteristics of a person can contribute to worsen his situation independently from the crime he committed. For example, nationality and ethnicity are used in the (automated) risk profile, meaning that some people with a certain nationality and/or ethnicity are disadvantaged, and that ethnic profiling is carried out. The Manifesto stresses that “ethnic profiling is a form of institutional racism, because it is part of government policy and instructions and leads to inequality between Dutch people with and Dutch people without a migration background.”

The Manifesto also underlines that there is a problem of police brutality in the Netherlands. Police have tools at their disposal which are used violently, such as the teaser, or they shoot to arrest. Moreover, according to the Manifesto little is done when police officers use violence or commit acts of racism, which therefore contributes to fueling police brutality as they know that there won’t be important consequences for their actions. At the moment, racism and discrimination are not considered as aggravating circumstances, which, according to the Manifesto, should instead be.

Moreover, the language is again a barrier. The Manifesto argues that “Papiamento, like Frisian, is one of the official languages within the Kingdom. It must therefore be possible to speak in Papiamento in court, as it also applies to Frisian.” In addition, the Manifesto states that “the government must provide free and voluntary language courses, without an integration obligation.” Indeed, there is a “compulsory integration course” that migrants and non-Dutch people are obliged to undertake when they plan to stay in the Netherlands for a long time, which however, according to the Manifesto, “deprives Black people and persons of color of the chance of an honest and sincere acquaintance with the Netherlands.” What is interesting is also that the Manifesto then says: “in neighborhoods with Black communities and communities of color, law enforcement officers must complete community training (integration) before they start working there, in order to get to know the environment and culture of the neighborhood in question.” Hence, the Manifesto advocates for the end of forced integration that migrants and non-Dutch people have to undertake once they move to the Netherlands and plan to stay there for a long time. At the same time, it advocates for an integration of policemen into certain neighbours in order to avoid unpleasant situations. This could mean that so far the culture integration has been unidirectional, meaning that people had to conform to the Dutch society culture, but that little has been done by the police and justice system to include the other cultures present.

From the word cloud, it can be noticed that “racism” and “discrimination” are the most used words after “police,” which is the main subject of this section. This means that according to the Manifesto, “racism” and “discrimination” are hugely present in the justice and security sector, and indeed it proposes some actions and policies that can be undertaken to avoid racism and discrimination.

Domain 8: Anti-discrimination provisions

When it comes to eighth domain of anti-discrimination provisions (or ‘antidiscriminatievoorzieningen’ (ADV’s) in Dutch), the Manifesto states that these provisions are currently not independent, and that they lack a diverse composition and therefore do not represent their target group. There is no affinity with the target group, and also knowledge on the problems this group faces is missing. Besides, the ADV’s seem to evaluate themselves, which hinders effectiveness and transparency. As a consequence, victims of racism and discrimination often do not report themselves at the ADV’s, meaning that the current numbers of discrimination do not accurately represent daily reality. Thus, according to the Manifesto the ADV’s need to be urgently and thoroughly reformed. A single national office with branches spread throughout the country needs to replace the different ADV’s. This increases efficiency and savings that benefit prevention, education, visibility campaigns, and research. General action points that the Manifesto suggests mostly refer to the lack of attention that is currently given to committers of racism and discrimination, and to the fact that victims are not sufficiently being motivated to make a declaration themselves. The Manifesto also envisions a role for advertising agencies with affinity with the topic here, as they should launch a multiannual media campaign with experiences of victims and information from contact points, to indicate to their wider audience that racism is punishable.

Then, with regard to the organization of the ADV’s, the Manifesto stresses the need for the independent functioning of the ADV’s, for anti-discrimination measurements based upon law and international treaties that protect minorities against racism and other forms of discrimination, and for direct and structural financing by the central government, with a fixed budget for anti-discrimination measurements and a separate budget for salaries. This implies that currently, all these measures are currently not at place in the Netherlands.

What could therefore be concluded with regard to Dutch society is that even though anti-discrimination measures are already at place, in practice these measures function poorly and are not according to the needs of those individuals they try to protect. Again, the issue of intercultural representation stands out in the Manifesto, as currently, people working for contact points for racism and discrimination do not represent their target group. This makes victims of discrimination and racism hesitant in reporting their experiences, leading to a misrepresentation of such acts in daily reality.

Domain 9: Media

In the ninth domain of media, the Black Manifesto opens with the statement that:

“Media inform society and therefore have a great responsibility. What we see, hear and read influences our worldview. Without a diverse and inclusive reflection of society, a one-sided picture is presented. It is anchored in the Dutch Media Act (2008) that media services provide a balanced picture of society and reflect pluralism. A code of conduct has also been included, with attention to procedures for reporting and suspected abuses. But in reality, media companies are mainly white and there is no safe organizational culture in which people dare to speak out against racism or other forms of discrimination in the workplace. The Black Manifesto argues in favor of combating anti-black racism in the media world, both in what is published and broadcasted, and in the organizational structure of media companies.”

This depicts the Dutch media as mainly white dominant, without the possibility to speak out against racism and discrimination. Moreover, the Manifesto highlights that the media organizations are not diverse and inclusive, and that there is a problem of income inequality “between white and black people in the media.” In addition, it is stated that “there must be a media protocol for tackling and combating racism and discrimination in the workplace and in productions, including a safety clause for employees so that they can speak out against racism and discrimination without negative consequences.” This underlines first of all that there is no such protocol at the moment, and secondly why people do not speak out against racism and discrimination: they will face negative consequences.

The Black Manifesto also calls for an effective inclusion policy, underlying how inclusion is not taken into consideration in the media organizations. It also stresses that the media should “represent a multitude of perspectives, making it clear that a white perspective does not equate to neutrality.” Moreover, stereotyping is something that happens in the media, as the Manifesto says that it “must be combated.” Finally, a lack of representation in the media is also a problem of the Dutch society, in particular there is no time dedicated to “news and background information about and from the Caribbean part of the Kingdom,” highlighting once again that the media are not inclusive.

Domain 10: Arts and culture

When it comes to the tenth domain of arts and culture in the Netherlands, the Manifesto states that for decades, museums and cultural institutes contributed to the (re)production of colonial imaging and the negative narrative of Black people and people of color. Black artists and professionals in the cultural sector are strongly underrepresented in arts collections, workforces, and receivers of subsidies. The arts and culture sector in the Netherlands insufficiently reaches Black communities and communities of color. For that reason, the Manifesto pleads for cultural facilities closely available to black communities, and for a different norm than the current white or eurocentric perspectives dominant in arts and culture. More knowledge should be invested in Black history, arts, and cultural heritage, to allow for a more complete view of Dutch history. This indicates that currently, a one-sided view on Dutch history remains dominant in arts and culture.

The Manifesto comes up with action points aimed at restoration, organization and education. With regard to restoration, the Manifesto mainly focuses on looted arts and cultural heritage, and depicts the Netherlands as not taking enough measurements to enable the safe return of arts work and give management back to those entitled to ownership. Besides, the Manifesto is critical towards the way historical figures that committed crimes against humanity or have been guilty of colonial crimes, are being praised as “heros for Dutch society” in public spaces and street scenes. According to the Manifesto, these figures should be placed in the right historical setting or even entirely removed.

When it comes to the organization of arts and culture, the Manifesto states that: “Museums and cultural institutes should hire black professionals at all organizational levels, and institutes should create a safe and inclusive work environment”. Thus, such a safe and inclusive work environment is lacking in Dutch museums and cultural institutes according to the Manifesto. The Manifesto also sees a shortage in room provided for black cultural institutes and artists in the arts and culture sector.

With regard to education within the arts and culture sector, the little room provided for black cultural institutes and artists comes back, in the sense that: “There should be more investments in centres for the emancipation of Black youths, to enable them to develop their talents”. This mainly refers to disadvantaged districts, where physical spaces should be provided for black residents to meet and engage in common (cultural) activities.

What follows from the way the Manifesto analyses the arts and culture sector in the Netherlands is that black arts and artists are still underrepresented in Dutch museums and cultural institutes. More attention should be paid to the colonial past and the lootings of arts and cultural heritage in this era, which also means hiring more Black professionals and artists to create an inclusive work environment. The Manifesto furthermore states that employees of cultural institutes should be trained in awareness about the colonial past and its heritage, white privilege, and antiracism, which implies that such awareness is currently still too low.

Domain 11: Sports

When it comes to the eleventh domain of sports, the Manifesto states that: “It is said that sport brings people together, but in the Netherlands sport is increasingly becoming a hotbed for discrimination.” It underlines that sport has been a breeding ground for racism and discrimination. Anti-black racist statements have been happening at both amateur and professional levels, and have been made by players, supporters, associations and coaches. The Manifesto sustains that they are not properly punished, and suggests some actions that should be taken, such as:

-

Matches must be terminated when racist expressions/chants occur and the offending supporters' club automatically loses the match.

-

The sports federations, in collaboration with experts and experts from the black community, should provide information and training on anti-black racism to referees, officials, players and employees of the sports world.

-

Sports associations, sports federations and sports clubs suspend cooperation with radio and TV programs that express themselves as racist and discriminatory.

Moreover, the Manifesto underlines that “sports federations should set quotas for greater diversity in key positions within the boards, boards and committees of sports such as football, basketball, baseball and boxing, where athletes from non-Western backgrounds participate.” This means that at the moment such quotas do not exist, making the sport organizations less inclusive and more discriminatory.

Domain 12: Aftercare

The final domain of the Manifesto concerns the delivery of an aftercare package for descendants of enslaved people, or the Afro-Dutchmen (‘Afro-Nederlanders’ in Dutch) as the Manifesto calls them. This group still deals with the consequences of the slavery past, and to do justice to these people, effective aftercare is needed. According to the Manifesto, an aftercare package would correct some of the deprivations that black people face. In general, the package would consist of the following points:

-

The Netherlands needs to remit all debts to countries that were involved in (neo)colonial relationships

-

Statues, street names and other praises of persons that have committed crimes during slavery and the colonial past should be removed from the street scene

-

The Netherlands should recognize that the true abolition of slavery took place only in 1873

-

Now that 150 years have passed since the true abolition of slavery, and on the eve of the memorial of July 1, 2023, the Netherlands should formally apologize for the Dutch contributions in slavery

-

The first of July should become a national holiday

-

Undocumented Surinamese people that are born before the 25th of November, 1975, should be entitled to Dutch citizenship, as they are born before the Surinamese independence. The historical injustice against Suriname and the Surinamese community obligates the Netherlands to stand up for the descendants of enslaved people, who are living in the Netherlands and/or strive for a better position at the labour market, for following education, and for the reunification of family

When it comes to the financing of the aftercare package, the Manifesto points to the government that should allow for a structural financing of the National Institute for Dutch slavery past and heritage (‘NiNsee’ in Dutch), similar to what happens with the National Committee for the 4th and 5th of May. According to the Manifesto, the Dutch government should also allow descendants of enslaved to change their surname without any costs attached, as well as to undertake a DNA-study on their African origin. This statement implies that such possibilities are currently not present.

Then, the Manifesto also highlights the role of research when it comes to aftercare, stating that: “There should be an independent study to the consequences of the slavery past, colonialism and institutional racism, under the direction of black experts and black institutes”, as well as “an independent study to the role of the government and the monarchy in the slavery past of the Netherlands”.

The Manifesto also points to the role that education plays in providing aftercare, and calls for a National Slavery museum that would foster a fully recognition of the slavery past of the Netherlands. The Golden Carriage with its colonial images that belongs to the Dutch royal house should go to this museum. Furthermore, an education trajectory should improve the inclusion and position of descendants of enslaved people at the labour market, which implies that this position is still subordinated.

All in all, from the aftercare package suggested by the Manifesto, it becomes clear that the Netherlands so far seems to fall short of providing sufficient care and support for descendants of enslaved people. More effort is needed to work towards recognition and support for those hit by the effects of the colonial past.

Want to learn more?

Further reading recommendations

Dutch

Zo ontleed je de uitspraken van een racisme-ontkenner

Hoe word ik een goede bondgenoot?

Institutioneel racisme in Nederland: wat het is, waar het zit, en wat jij eraan kunt doen

'Je moet de onderdrukking blootleggen' – De Groene Amsterdammer

'Racisme zit in kleine dingen'

English

Videos & Podcast

Dutch

Rasioneel

Wat Je Niet Leert - Beluister Special: onbewust racisme | Podcasts

Sources

- Anderson, M. (2016, August 15). The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter emerges: Social activism on Twitter. Pew Research Center. Retrieved on November 24, 2021, from History of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter: Social activism on Twitter | Pew Research Center

- Black Manifesto Official Website: https://zwartmanifest.nl/home/

- Chambers, M. (2020). American Studies in the Archive. The Americanist. Retrieved on November 24, 2021, from PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

- Cottingham, M. D., & Andringa, L. (2020). “My Color Doesn’t Lie”: Race, Gender, and Nativism among Nurses in the Netherlands. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 7, 1-11. doi:10.1177/2333393620972958

- De Witte, M. (2019). Black citizenship, Afropolitan critiques: vernacular heritage-making and the negotiation of race in the Netherlands. Social Anthropology, 27(4), 609-625. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.12680

- Hart, C. (2008). Critical discourse analysis and metaphor: toward a theoretical framework. Critical Discourse Studies, 5(2), 91-106. doi:10.1080/17405900801990058

- Hoorntje, D. (2021, July 4). Wie zijn Black Lives Matter (en wat hebben ze bereikt)? One World. Retrieved on November 23, 2021, from Wie zijn Black Lives Matter (en wat hebben ze bereikt)? - OneWorld

- Kazarjan, N. (2021, May 27). Hoe is de situatie in Nederland een jaar na de Black Lives Matter-protesten? BNNVARA. Retrieved on November 25, 2021, from Hoe is de situatie in Nederland een jaar na de Black Lives Matter-protesten? - BNNVARA

- NL Times. (2021, March 12). Black community launches manifesto against institutionalized racism. Retrieved on November 24, 2021, from Black community launches manifesto against institutionalized racism

- NL Times. (2020, June 24). "We really need to stamp out racism": Rutte after discriminationtalk. Retrieved on November 28, 2021, from "We really need to stamp out racism": Rutte after discrimination talk

- NOS. (2020, June 7). Black Lives Matter-demonstraties in Zwolle en Maastricht. Retrieved on November 26, 2021, from Black Lives Matter-demonstraties in Zwolle en Maastricht | NOS

- Spijkers, C. (2020, November 30). Halfjaar na het Damprotest: wat heeft het teweeggebracht? NOS. Retrieved on November 24, 2021, from Halfjaar na het Damprotest: wat heeft het teweeggebracht? | NOS

- Stewart, L. G., Arif, A., Nied, A. C., Spiro, E. S., & Starbird, K. (2017). Drawing the Lines of Contention: Networked Frame Contests Within #BlackLivesMatter Discourse. PACMHCI, 1(122), 1-23, doi:10.1145/3134920.

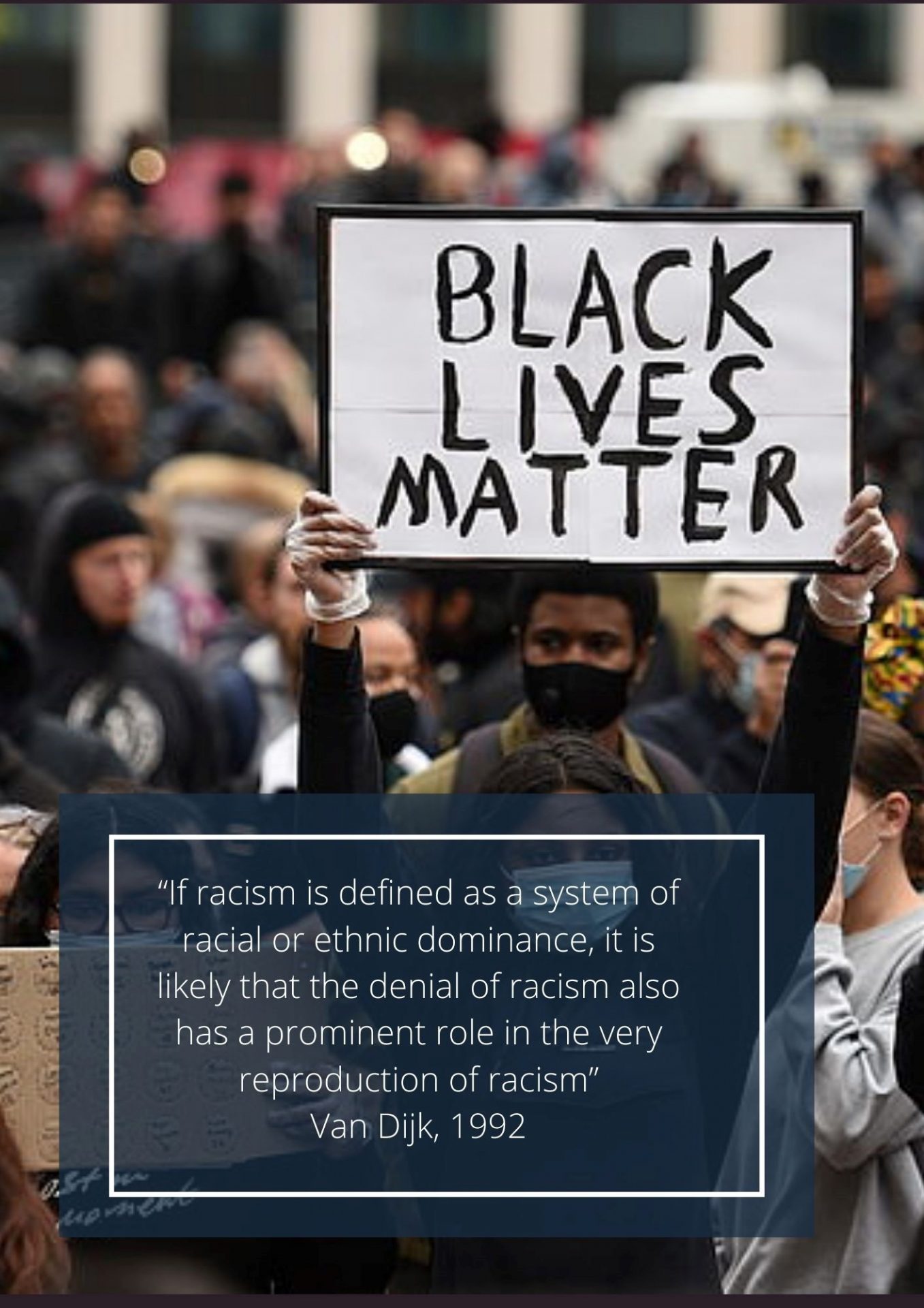

- Van Dijk, Teun A. (1992). Discourse and the denial of racism. Discourse and Society 3(1), 87118. Excerpt as Chapter 32 in The Discourse Reader.

- Wekker, G. (2016). White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Durham: Duke University Press.