By Chiara Cozzatella and Salomé Hindrinks

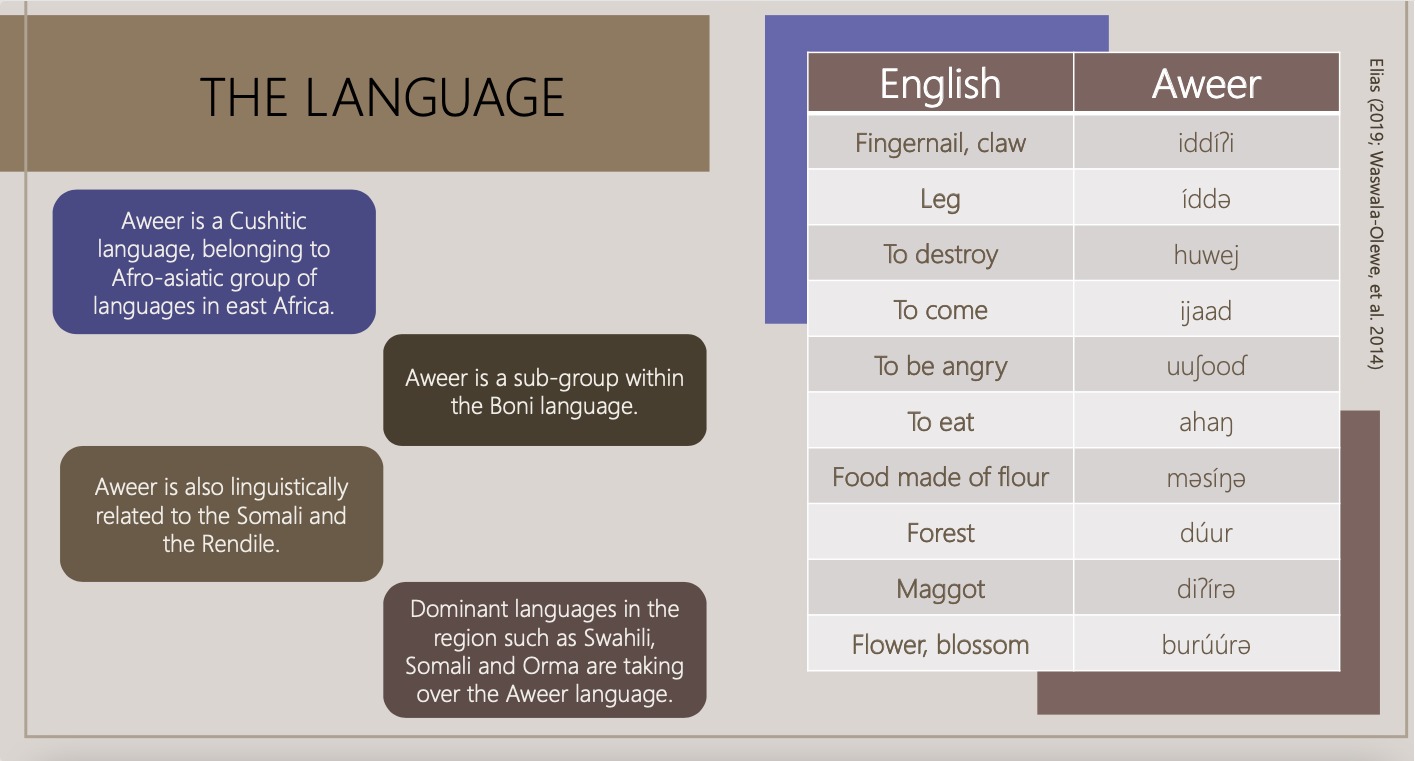

In our search for an endangered language, we had to opt for one which had documentation to be able to have some information to share. This highlights the importance of archiving languages especially those (severely) endangered since without archived information they are not represented and are in greater risk of being forgotten. We then settled on the Aweer language, spoken by the Aweer people in Kenya.

The Aweer People

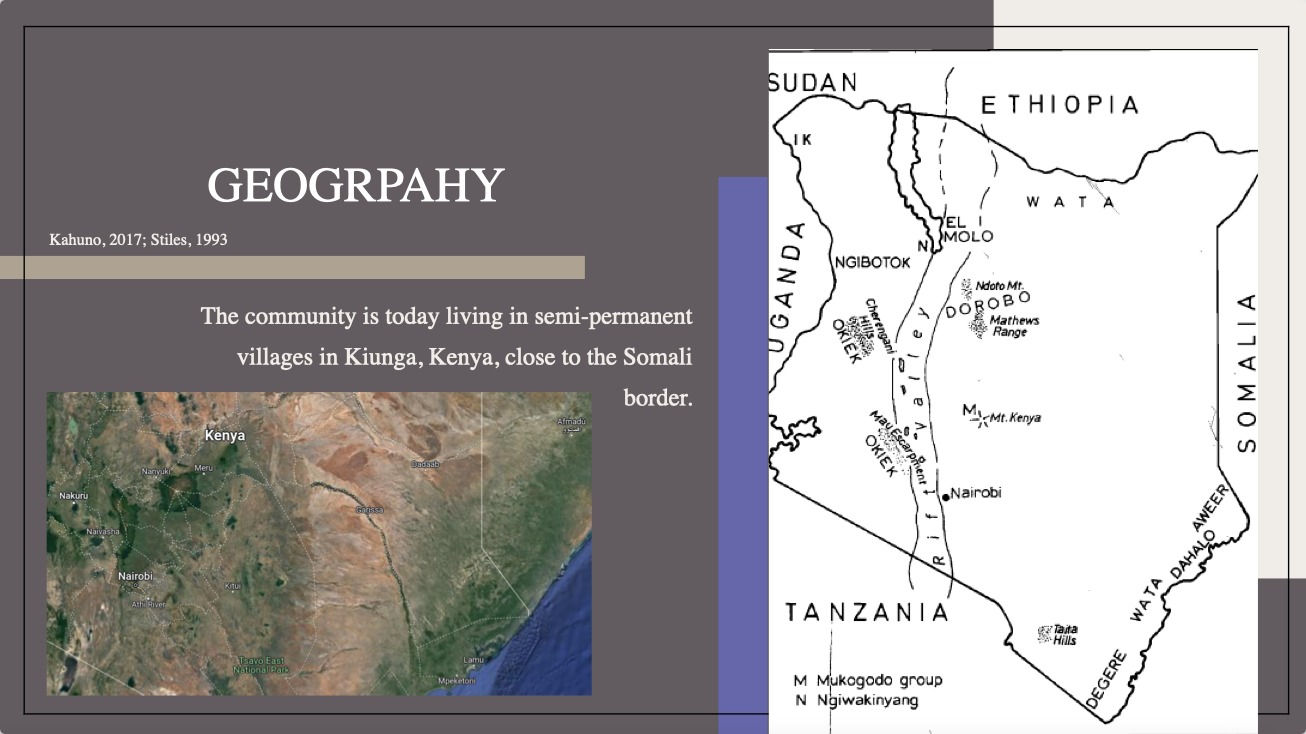

The Aweer people consist of approximately 5000 people. However, the language is currently only spoken by less than 200 people, making it endangered (Endangered Language Project). The Aweer are historically hunter-gatherers, who partially turned to agriculture in 1977, following the Kenyan ban on hunting. The area in which they are established though is of low agricultural value (Stiles, 1993). The denomination “Aweer” itself refers to the practice of hunting. The Aweer people, also pejoratively named ‘Boni’, are considered a “vulnerable group”. Their area is indeed the battlefield in the conflict between Kenya and Somalia, which started in 1963 and is still ongoing (Kahuno 2017). The name ‘Boni’ is pejorative, as it is the Somali appellation for various lower class groups who were constituted by liberated slaves in the area, who were hunters. This is the reason why we choose to refer to them just using the name Aweer.

Additionally, The Aweer community lived on customarily-held land for over a thousand years, however they continue to be regarded legally as “squatters” with no right to further their social and economic objectives. Despite the fact that these rights are outlined in the law, they have not been granted them in this designated region. For instance, locals who reside in Dodori National Reserve and pick honey and fruit are harassed by wildlife management officers, who frequently arrest and prosecute them. (Nunow, 2012).

The Aweer have historically practiced their traditional religion and values. They believed in a supreme being that was worshiped together with the ancestors, traditionally represented by the trees of the forests. In the Aweer community, there was a traditional distinction in roles between women and men: while men were hunting, women generally built houses and took care of those. As of today, while men keep hunting and usually sell part of the chase, women collect water and take care of water collection and carry out various manufacturing activities. Endogamy was practiced, together with polygamy. Marriages were well celebrated, with rituals, body paintings, clothing and music. Women’s chaste was a fundamental value. Infibulation was the common procedure and still is, not only on girls but also on women after delivery. In the 1950s the community converted massively to Islam. The traditional religion with its rituals is still practiced, in a syncretic form that is adapted to fit Islam (Kahuno, 2017).

"Ngoma"

Dance, “ngoma”, is an important component of the community’s life. The dancing performance is a symbolic moment to sustain tradition and cultural identity. Indeed, ngoma is a representation of rivalry between indigenous communities in the past. Belonging and cohesion are generated in the dance. Men traditionally perform the “ngomela”: in a semi-circle, they clap to the rhythm of drums (from which the name of the dance). (Kahuno, 2017).

Below is an audio recording for evangelism and Bible teaching in the Aweer language. Language is especially important to the ear, so we found it necessary to provide a sample of the language to the ear.

Reflection on endangered languages

Languages carry the cultures and histories of communities. With the languages come different knowledge. If languages go extinct the knowledge linked to them disappears as well. This can be seen with Aweer as their community gets chased from their land and the language is becoming less used as it is overtaken by dominant regional languages. The unsustainable use of their land by others endangers the loss of natural resources, land degradation and forest cover change. This is a direct consequence of loss of traditional indigenous knowledge. Thus, it is important to try to save endangered languages not only for the culture through artifacts and stories but also because of the historical knowledge the communities have on the land.

Bibliography:

Elias, A. (2019). Visualizing the Boni dialects with Historical Glottometry. Journal of Historical Linguistics, 9(1), 70-91.

Global Recording Network. Aweer Language: Aweer - Acts of the Holy Spirit. Retrieved from: https://globalrecordings.net/en/language/bob

Kahuno, M. N. (2017). Constructing Identity Through Festivals: The Case of Lamu Cultural Festival in Kenya. (Master Dissertation). University of Pretoria. Retrieved from: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/62642/Kahuno_Constructing_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Kiunga Youth Bunge. (2020, March 30th). The Aweer Community. Youtube. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PbgUWjOGkcg

Nunow, A. A. (2012). The Displacement and Dispossession of the Aweer (Boni) Community: The Kenya Government dilemma on the new Port of Lamu. Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing II (Cornell University). Retrieved from: https://cornell-landproject.org/download/landgrab2012papers/nunow.pdf

Stiles, D. (1993). Kenya Past and Present. Sabinet African Journals, 25(1), 39-45. Doi: 10.10520/AJA02578301_122

Waswala-Olewe, B. M., Andaje, S. A., Nyangito, M. M., Njoka, J. T., Mutahi, S., Abae, R., & Amin, R. (2014). Natural resources utilization by the Aweer in Boni-lungi and Dodori national reserves, Kenya. Tanzania Journal of Forestry and Nature Conservation, 83(2), 27-43.