The research was conducted in 2018 by Tamaryn L. Crankshaw, Micheal Strauss and Bongiwe Gumede in Gauteng, South Africa. It was published in 2020 on Reproductive Health.

“The right to dignity and the right to education cannot be compromised by the circumstance of being born young, female and poor”

-

The study

South Africa is the most unequal country in the world. Menstrual Health Management (MHM) is a relevant matter to consider when looking at female education: data from some African countries suggest that female learners, especially the youngest ones, may miss school due to their menses. The scientific community has long called for a more holistic approach to MHM. The topic implies important elements, such as the issue of dignity and social justice as well as the possible linkages between MHM and school absenteeism of young girls. These matters should be addressed by national governments and international organizations. Challenges faced by girls in managing their menses can be massive, mostly if access to modern sanitary products and good facilities is not guaranteed in schools. The researchers wanted to explore these linkages and understand the main needs that should be addressed.

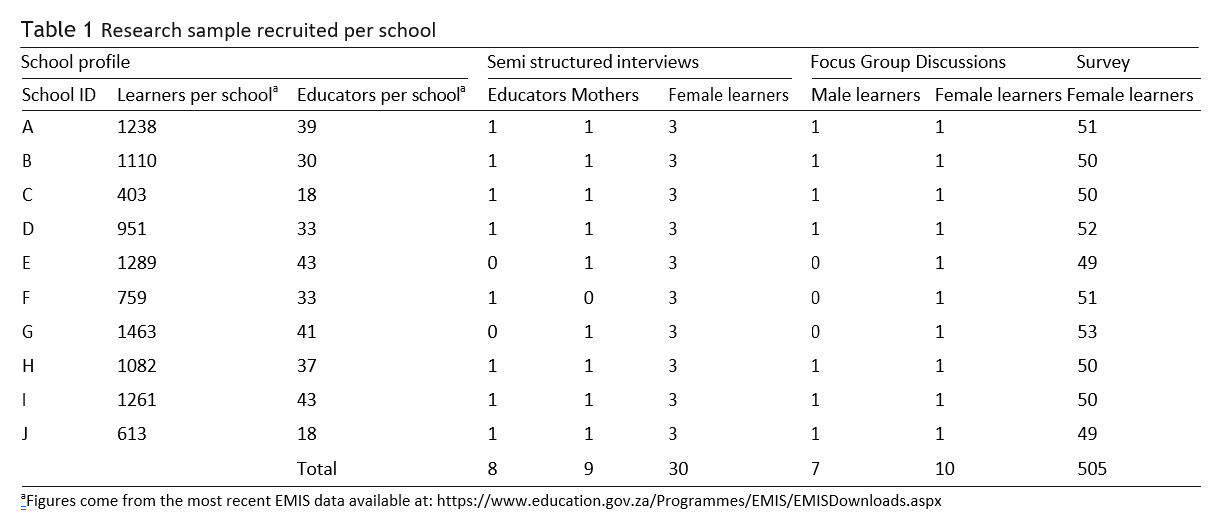

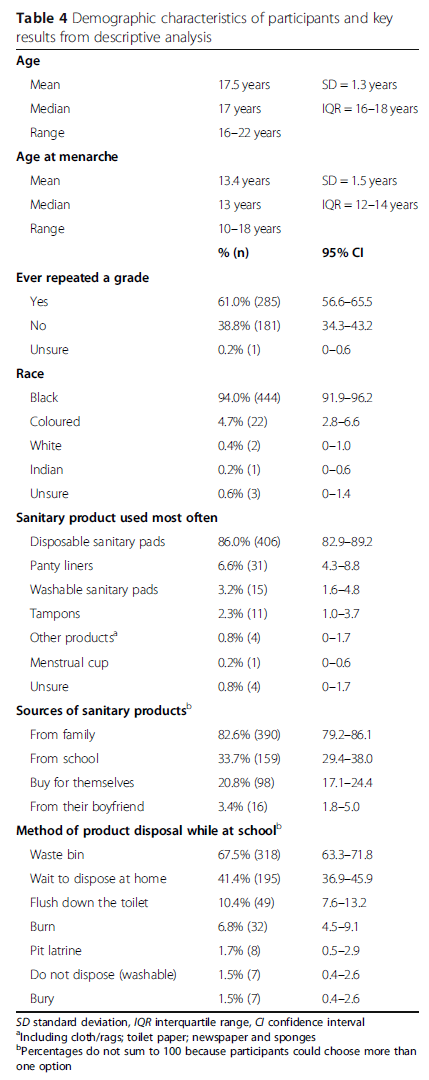

The study took a sample of 500 girls in 10 public schools in the Sedibeng district, the second largest in the Gauteng Province in South Africa. Even though the district is highly urbanized, it is the least densely populated in the province, nevertheless poverty levels are high, with an estimated rate of 21% in 2014. Two of the schools where the study was conducted were classified as ‘rural’, while eight were ‘urban’. Participants, who were selected through convenience sampling and with the help of the educators, were 16 years or above, with an average age of 17. They were mostly students as well as educators and mothers who had a daughter enrolled in a study school. Interviews and focus groups were conducted in Sesotho and translated into English. Emergent themes were identified in each domain through an iterative process.

A mixed method, transdisciplinary study with an interdisciplinary team

The study team itself was interdisciplinary, consisting of two health economics researchers and a human rights and labor history researcher. Therefore, the study was transdisciplinary and conducted with the insights of all the authors. Concentrating on health and economics, as well as human rights and policy, the research was carried out with various approaches, focusing on social science, women’s health, and reproductive rights.

The study was realized with mixed methods, analyzing both quantitative and qualitative materials. The methodology has shaped the research and the results obtained: the quantitative data can be better understood with the help of qualitative data, which gives us a background. Indeed, while the data presented show a screening of the participants in the study, the qualitative data brings the reader to comprehend more deeply the challenges faced by the participants with their period management.

The quantitative method was employed in the study through a self-administrated survey with the purpose of determining access to products and the dynamics of girls’ absenteeism from school related to MHM. The demographic profile of the students was also analyzed in this way, to contextualize the social stratification in connection with access to sanitary products. The method used to analyze the results were descriptive statistics.

The qualitative method was implemented through focus group discussions (7), both with female and male learners, and individual interviews with female learners (30), some of their mothers (9), and a few educators (8). The method used to analyze the results was thematic analysis through the identification of main domains. A confrontation with existing literature was also carried out, and findings were broadly confirmed.

[When they are menstruating] they are not as involved as other days especially in the lower grades; the seniors are just fine from grades 10 until 12, but in grades 9 and 8, you see elements of them being embarrassed. I think it is because they are experiencing a process that is fairly new to them. (Educator, School C)

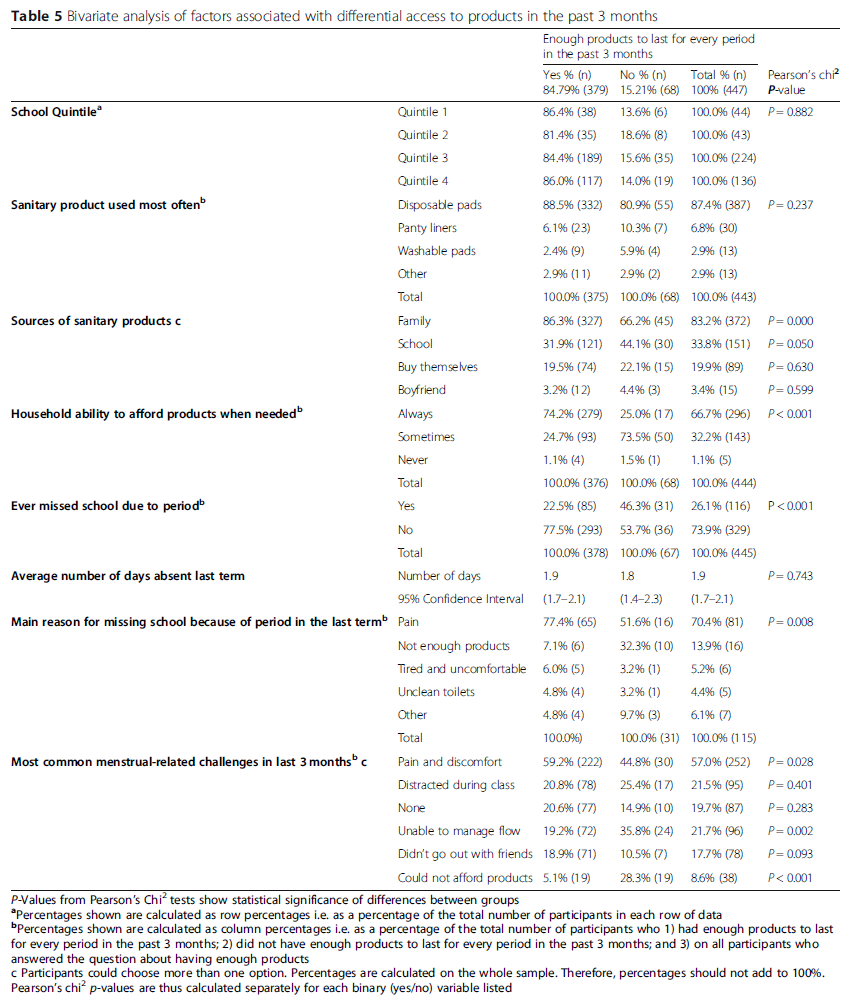

A combination of methods was realized through triangulation of both kinds of data. The key findings, reported below, were analyzed through a bivariate statistical analysis of the outcomes from the different data obtained.

The unequal access and distribution of sanitary products is an issue for girls in Gauteng: it has relative consequences on their absenteeism from school. These were observed in relation to the participation and outcomes of female learners in class as well as on their physical and mental wellness (physical discomfort, dysmenorrhea, anxiety). The lack of hygienic facilities in schools has also a massive impact on the elements listed above.

I cannot use the toilets because there is no water which makes me not to focus because all I am thinking about is the clean toilet at home that I can use to change my pads. You have to wear this big night pad so that it can last you until after school and then next thing you are smelling … I cannot focus. (Female Learner, School D, Interview PID 11)

Deficiencies and issues were also reported regarding the distribution of pads in the schools.

You see Mam these teachers don’t give us pads, you see this teacher who is passing by? She is the one who locks the office and only give pads to her favourites. Some of us cannot afford pads but she says I can afford just because am wearing Chino pants (good quality trousers) to school. What if my uncle bought them for me? How does she know? (Female Learner, School H, PID 23)

Cultural bias seemed to have a relevant significance, for what the authors called “Unmet Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Needs of Learners” referring to the understanding of the period and lack of sexual education. Taboos were also broadly encountered, for matters such as the use of tampons or menstrual cups as well as for the management of teasing in class.

No, I don’t know [why girls and women menstruate]. I just know that dirty blood must come out and you must count 28 days before it comes out again but I do not know what happens inside. (Female learner, School D, PID 12)

Mam we need education, these teachers don’t teach us about everything you have been talking about. We need a person who can come to our school at least once a week to educate us and give us support because these teachers sometimes swear at us and say we are using contraceptives. We also need a school nurse, if you go to the clinic for help. Yooh they will swear at you until you leave. (Female Learner, School G, PID 21)

Conclusion

The methodology used to conduct the study has proven to be beneficial to the research. While there was, according to the authors, a “high level of convergence between the qualitative and quantitative findings”, the mixed methods were, in this case, a valuable combination to present the study. Indeed, this made the research more complete and clearer and, hence, approachable also by non-specialists. The purpose of giving evidence to enable policy interventions on the topic seems to be fulfilled. In this way, the study was concluded with a call for action on the provision of sanitary products together with better management of MHM and sexual and reproductive health.

References:

Crankshaw, T. L., Strauss, M., Gumede, B., 2020, Menstrual health management and schooling experience amongst female learners in Gauteng, South Africa: a mixed method study, Reproductive Health, 17:48, 1-15