Fela’s voice comes blaring out of the radio of a danfo bus filled with commuters; the MP3-player of the Uber driver has his music on it; a university professor’s ringtone is one of his songs and many Lagosians can sing along with most of his lyrics. Nigerian artist Fela Kuti may have died in 1997, but in today’s Lagos his music is just as popular as it was a couple of decades ago. To many Lagosians, his songs have lost nothing of their relevance and his call for liberation is as topical now as it was then. Let’s take a closer look at some of his lyrics.

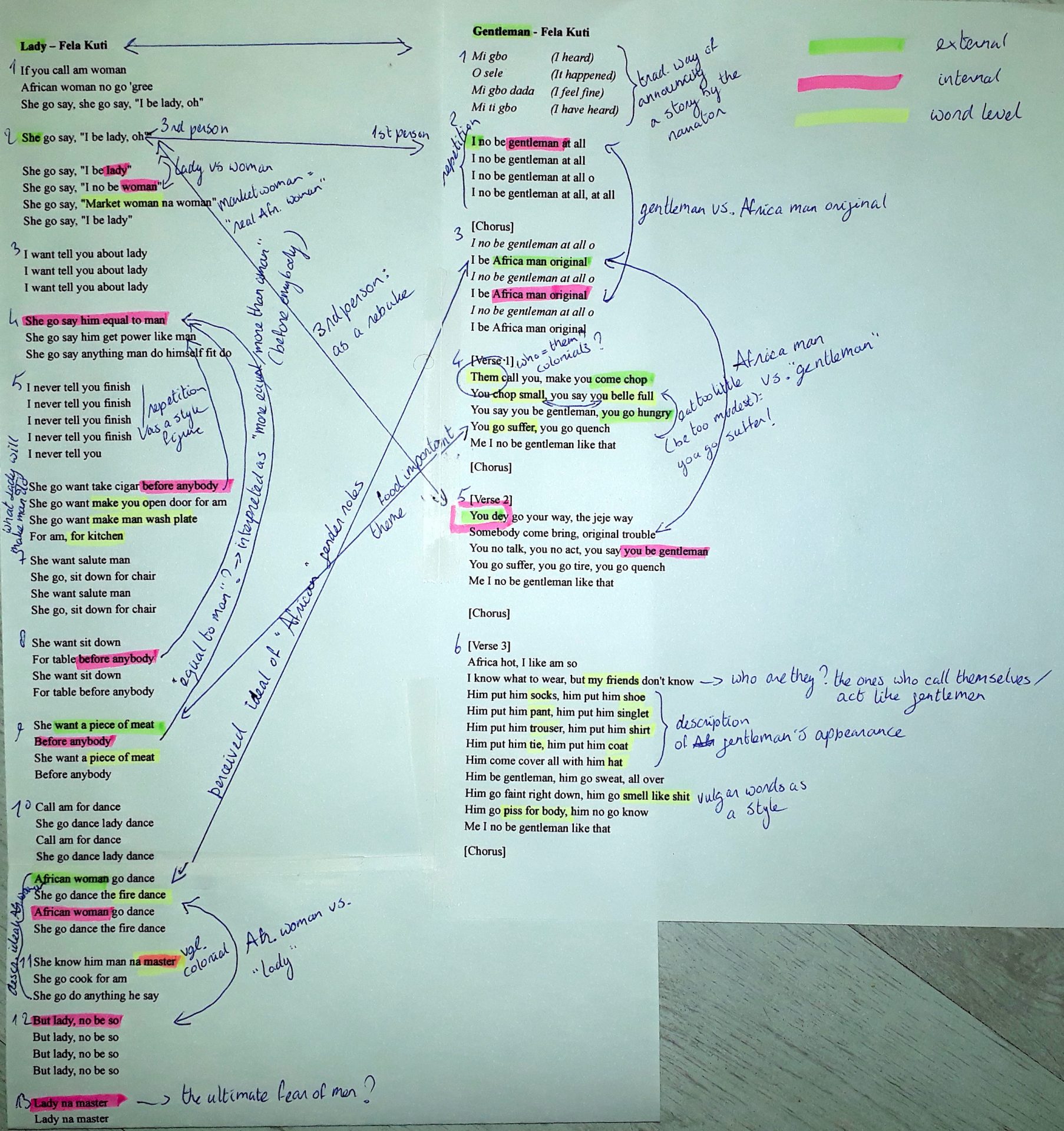

For this Critical Discourse Analysis, I chose to close-read and compare two of Fela Kuti’s songs: Lady and Gentleman. For the superficial listener/reader, these two songs might seem to represent two sides of the same coin: both are an indictment of the adoption of the colonial perception of gender by his fellow Africans. The narrator is advocating a return to African values of gender and gender roles. The words lady and gentleman are being used as representing the British idea of gender, and they are placed in a dichotomy with African woman and African man. As such, the songs represent the anti-colonial discourse that Fela Kuti became famous for, fighting for the liberation of his people from the yoke of the British colonial empire. But what is he really saying?

First I will analyse the two songs separately on a word, sentence and internal textual level. Then I will make an intertextual analysis of the two song texts, after which I try to draw a conclusion about the true meaning behind these seemingly similar narratives. The lyrics of both songs are to be found underneath this analysis. I have numbered the paragraphs for an easier means of reference.

About the language

Before I start looking at the individual texts, I should address Fela’s language itself, which is one of the keys to his popularity and also has its hidden meaning. Although he came from an Yoruba elite family in Abeokuta where Yoruba and English was spoken, Fela always sang in Nigerian Pidgin, the lingua franca on the streets of Lagos – and of the Nigerian south.

Pidgin is much more than a simplified English: it borrows from other languages like Yoruba, Urhobo an Igbo and to a lesser extent from Portuguese. The grammar of Pidgin is adjusted to the needs of its users and as such has travelled far from the English language, in fact, an English speaker hearing Pidgin for the very first time will miss a lot of its meaning.

Fela sang in a language hard to comprehend by the coloniser, but very well understood by the Nigerian masses. The sheer use of Pidgin by Fela as a way to communicate was an act of defiance.

Lady

Let’s first turn the attention to Lady. In this song, the narrator mostly speaks of a third person (she) and only uses the first person narrative when he wants to captivate the audience’s attention or assert his authority. Speaking about a third person creates distance: he is not talking to people (women), but about people (women). The third person female in this song is the lady the narrator is criticising, the African woman who no longer wants to be called woman: I no be woman, I be lady.

With the word lady comes a whole set of values which the narrator then starts describing. She go say him equal to man, is the first bone of contention. Verse 4 narrates how ladies claim the same rights as men (power like man, anything man do himself fit do – anything a man can do a woman also can do). Basically it describes how these women are claiming equality.

But then the narrator tells the audience to keep listening (Verse 5: I never tell you finish – I haven’t finished the story), because it gets worse: not only does the lady claim equality, she claims more than that. From verse 6 to 9 the narrator describes how the lady wants everything to herself, including cigars (the smoking of which at that time is a very British male prerogative by the way), and she wants it first (She want a piece of meat before anybody). Herein lies the fear of the narrator, it seems, the man who is afraid not only to be equal to women, but to be oppressed by them.

Verse 10 is the first one that contrasts the (Western) lady to the African woman, as it speaks of the way these types of women dance. The lady who modelled herself according to a Western image dances the lady dance (verse 10 – referring perhaps to the stylised steps of ball room), while the African woman dances the fire dance, the narrator states, in a hard to escape sexual connotation from the male gaze. In both cases – as through the entire text – the woman is an object, rather than a subject.

What follows is the male narrator’s description of the ideal African woman’s behaviour, making it clear that this is the definition of womanhood as he sees it. All this is defined by her behaviour towards the man. Verse 12: She cook for am / She go do anything he say and most poignantly: She know him man na master- She will know that the man is her boss. Tthe narrator not just describes how an African woman ought to behave, he also places her clearly below the man in the hierarchy of society: the African male is the boss.

The very last phrase paints the picture of the way the world would be if the westernised ladies got their say: Lady na master – the woman is boss. Note that in Nigeria and in other British colonies, the word master is also used in reference to the colonial power – exactly what Fela fought against. I will address this issue further in my conclusion.

Gentleman

In the second song, the narrator uses the first person perspective a lot: he is speaking of himself, as a man. Verse 2 reads as a declaration of independence. I no be gentleman at all, the narrator sings I be Africa man original, which can be interpreted as ‘I am not the kind of man the British coloniser want me to be, I am an original African’. When he changes narrative perspective in verse 4, he turns to the second person. By addressing the (male) audience as you the narrator is talking to them, not about them. Thus the narrative comes across as an inclusive talk amongst men.

The text then goes on to describe the behaviour of these gentlemen. Interestingly it doesn’t do so in relationship to women, but in relationship to the colonial power. In the first line of verse 4 (Them call you, make you come chop) the ones inviting the man for dinner are the British, and the narrator ridicules how the invited gentleman out of modesty does not eat enough and ends up hungry. Here food can be seen as a metaphor for much more : if you are too modest and don’t take what you need, you’ll end up impoverished and weak.

Verse 4 ends returning to the first person narrative: I no be gentleman like that. The next verse has the same structure as the preceding one, starting with a description ridiculing the behaviour of gentlemen and ending with the assurance that the narrator is not like that.

The narrator turns to his friends who have changed into gentlemen in the last verse. The use of the word friend creates an intimate atmosphere in which the following statements do not come across as harsh as they could have. It starts innocent enough with a detailed description of what a gentleman dresses like. But then the narrator becomes vulgar, stating that because of the overdressing gentlemen smell like shit and piss themselves. Even phrased so brashly – or maybe beacuse of it – the conversation comes across as a talk amongst mates, equals.

It cannot be surprising that the narrator concludes the song by reassuring that he is not such a gentleman. Note that nowhere the text describes what an African man is, only what he is not. Also note that women are not mentioned at any point.

Comparison and conclusion

The most striking difference in the two texts is the narrator’s use of perspective. The ubiquitous third person in Lady makes it a song about women, objectifying rather than addressing them. The result is a patriarchal discourse: here is a man telling women how to behave. The abundant use of the first person perspective in Gentleman however places the narrator on the same level as the men he is addressing, making the message a much more empowering one. Here is a man liberating himself, speaking to his fellow men and urging them to do the same.

Once you start looking at these two song texts in this way, the conclusion becomes almost inescapable: whereas the second one is about (men’s) emancipation, the first is about (women’s) opression. That women are not even mentioned in the second text, is revealing: it is not them that African men need to worry about, but it is the coloniser. Also, it is not a coincidence that Lady meticulously describes how an African woman should behave, where Gentleman leaves out such a description for men all together – it only states what African manhood is not. Interconnecting both narratives, you could conclude that the African man is free to define his gender (role) as long as the African woman accepts him as her master.

Fela does not want to be ruled by a master, but at the same time in he does not hesitate to impose a master on women. Zooming out from these two texts to Fela Kuti’s life and politics, in my view this is exactly where his activism is flawed. A lot of times, his narrative of liberation seems to be lopsided towards the male perspective.

His chauvinism is all the more surprising because in his personal life, Fela experienced empowered women from up close. His own mother was the first Nigerian woman to drive a car and a women’s rights activist. His Yoruba background would also have confronted him with women in roles of power. The second verse of Lady mentions market women, which is striking. In the Yoruba context, market women are a force to be reckoned with, and the Iya Loja – mother of the market – is the most powerful person in the most important public space of society.

The precolonial role and status of women in Yoruba society was much less submissive and marginalised than the part Fela would want them to play now. In that sense, Fela’s activism might be more tainted by the colonial experience than he’d like to admit. It is fascinating to experience to what kind of reflections close-reading two song texts can lead.

|

Lady – Fela Kuti [verse 1] [verse 2] [verse 3] [verse 4] [verse 5] [verse 6] [verse 7] [verse 8] [verse 9] [verse 10] [verse 11] [verse 12] [verse 13] [verse 14] |

Gentleman – Fela Kuti [verse 1] [verse 3] [verse 4] [verse 5] [verse 5] |

Mirjam de Bruijn

October 7, 2020 (20:38)

Thanks for showing your notes; that is what it is reading and re-reading and giving it meaning. The comparison works very well. it opens an interesting perspective indeed on the position of Fela Kuti with respect to gender. Probably he was himself not aware of it.