Portfolio - Klara de Groot

Klara and Maya discuss the role of historical information in constructing shared national identities, the history of the Ugandan education system, and the extent to which it has (or has not!) been decolonised today.

Studying History, Identity, and Education: Thematic Considerations

The act of history writing is an immensely powerful one. By constructing a narrative, perhaps by drawing from different elements of various local cultures, or even creating an entire myth from scratch, historians have the power to create the backbone of, to use Benedict Anderson’s terms, a national ‘imagined community’. The history of the Ugandan school curriculum, and the way in which it has developed with (and sometimes against) the decolonization process, shows just how powerful a role historical education plays in the formation, consolidation and evolution of personal, national and regional identities. On paper, Uganda’s school curriculum was ‘decolonized’, that is to say, reevaluated and restructured by the Ugandan ministry of education after independence in 1962. But the question remains: how is curricular decolonization even possible when the entire concept of a curriculum was itself a colonial imposition?

As over a century of scholarship has demonstrated, history teaching in schools (and in the public) contributes to identity-building. By constructing narratives of past events in a teleological framework, and imbuing the images and characterisations contrived from them with historical, political and cultural gravitas, history teaching allows for the creation of a shared identity. Most significantly in recent years, we have seen how, as Hobsbawm puts it, schooling is the “most powerful weapon for forming […] nations”.

With this in mind, one can only assume the power that a history curriculum holds over young minds, which is why it is so important to keep on revising those curricula, to rid them of ideology and alternate motives. In the case of Uganda, especially regarding what we have learned about its history, and the fact that the curriculum itself started out as an ideological instrument, this is a particularly challenging topic. Second, people’s ethnic, national, regional, and global identities influence their political behavior, as well as their behavior towards others. As Mino aptly puts it in History Education and Identity Formation, ‘beyond simply teaching the past, History education builds the foundation for an individual’s national identity by transmitting the myths and values of the nation.’

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

Colonial Origins of Modern Ugandan Education

In 1877, when Christian European missionaries arrived in what is now Uganda with the aim of introducing European-style schooling and evangelism, some indigenous leaders, who had the expansion of their tribe’s political power in mind, welcomed them. In the Buganda kingdom (one of the biggest ethnic groups after which Uganda is named), chiefs and servants were instructed on Christianity, literacy, arithmetic, agriculture and history – all of which were taught through a religious and Eurocentric lens. Though additional influences by Catholic missionaries and Arab traders led to conflicts and tensions, British Protestants maintained the upper hand in the kingdom and maintained control over educational materials.

In 1894, British control over the region was formally established through the Uganda Protectorate. Since then, Ugandan education has existed in two forms: ‘traditional’ education (in which children are educated at home via proverbs, storytelling, oral histories and the moral teachings of elders), and ‘official’ education (in which children follow a centralized curriculum at school, and are assessed via formal examinations based on Western models). By imposing the second form in an attempt to ‘civilize’ Ugandans, British hegemony pushed traditional education, and consequently native Ugandan knowledge and culture, into a position of perceived irrelevance. The dissonance between these pedagogical forms is especially pronounced given Uganda’s ethnic and cultural diversity. Uganda’s current national borders are still based on colonial ones, which the British imposed without regard for existing sociopolitical systems by which fifty-or-so native tribes organized and governed themselves. The latent consequence of this negligence is that, rather than allowing for an organic sense of unified ‘Ugandanness’ to flourish, bottom-up traditional education in Uganda remains fragmented according to ethnic and tribal lines. As we shall see, the successful construction of a unified sense of national identity tends to be contingent upon a shared sense of history, but neither the top-down Eurocentric perspectives of the British curriculum, nor the heavily fragmented bottom-up teachings of diverse tribal teachings could facilitate this.

This was far from accidental.

Though state control over education increased via the establishment of a ministry of education, and Christianization was heavily encouraged, British colonial policy in Uganda remained guided by ‘divide and rule’ principles. In actively facilitating ethnic and tribal conflicts, and preventing Ugandans from relating positively to each other though, for instance, identifying with each other historically, this policy aimed at preventing the potential dangers posed by the native majority collaborating against the British minority. While this period saw a marked rise in European nationalisms, colonial influence prevented Uganda from relating to the newly established ‘nation’ at all. Indeed, though its borders coincide with that of modern Uganda, diffused Ugandan identity today can be traced to the fact that the Protectorate of Uganda was never intended to be a national unit for the benefit of its native people – it was instead designed as a source of British wealth and geopolitical power.

Consequently, though most Ugandans did not attend formal education, those who did were actively instructed to consider themselves developmentally, historically, technologically and spiritually subordinate to their British ‘masters’. Besides religious education, one of the most powerful tools by which to justify British colonial rule was through history. Education was thus used and abused in several ways, also to help justify the subordination of the local people to British colonial rule. For example, British commissioners controlled the curriculum, mitigating any information that was identified as knowledge that would potentially undermine colonial authority in what Greene calls ‘carefully chosen silences’ (Greene, Creating a Nation Without a Past, 106). In short: British history was taught, African history was not. Given that these were the foundations of the modern curriculum, it is safe to say that from the start, historical education was a strong instrument in weakening native confidence in Uganda’s political ability, cultural relevance, or national power.

Let us also give an example to demonstrate how Eurocentric the curriculum was in these times. The overall message of the syllabus was: Africa owed its development, indeed its very place on the world map, to European initiative. In a History school book, a section called ‘The Dark Continent – Filling the Map of Africa’ taught students about the ‘exploration’ of Africa; The teachers were instructed to begin the section with a large sheet of paper on which they drew a map of the Mediterranean and West Europe, representing the then known world. Africa was to be left blank and then filled in little by little. To contrast this with a later development, an official from the Ministry of Education said that, “Instead of saying Speke ‘discovered’ the source of the Nile we are now saying he was the first white man to say it” (quoted after Greene, Creating a Nation Without a Past, 116).

Before Ugandan independence in 1962, there was a process of preparation, where Ugandans were educated in order to obtain the necessary skills and knowledge to govern their nation. Some would argue that this was also a chance for the British to place those who would remain loyal to them into positions of power. Buganda Kabaka Muteesa II became the first President of Uganda, Milton Obote became its first Prime Minister. Instead of reintroducing traditional education, the British system was ‘revamped.’ The school curriculum, especially History, was Africanized and nationalized to promote a Ugandan and an African identity. During Muteesa’s, and later Obote’s rule, efforts were being made to centralize education, and thus to rid it of religious and ethnic influences. Still, hangovers from the colonial period meant that ethnic and trival divisions remained severe.

During Idi Amin’s rule, education was not a priority, and his rule also led to the institutionalization of unequal treatment of the different ethnic groups, as he favored some more than others. After several interim leaders and power struggles, the National Resistance Army declared their leader, Yoweri Museveni, the new president in 1986 (a position he maintains today). In the guerilla war that they had waged, many schools were destroyed, and the continuation of education was hindered.

Education has since become more nationalized and, overall, top-down efforts to strengthen Ugandan national identity have increased in success. Some of Museveni’s supporters formed the National Resistance Movement, which has advocated the inclusion of all Ugandans, regardless of their ethnicity, ideology, or previous political affiliation. The education program of the NRA (chacka-mchaka) has been incorporated in today’s Social Studies curriculum for the primary schools.

The idea behind nationalized History education was that it would change people’s perspectives towards others on a national level, and fostered relatively more peaceful interethnic relations. At the same time, however, the emphasis on schooling has also led to a deepened decline of traditional culture and education – a tension we explore in our podcast.

Ugandan Education Today

There are, of course, also practical challenges to consider when it comes to studying the Ugandan education system, though we did not believe they were within the scope of our theory-based podcast. For instance, school enrolment rates in Uganda have heightened rapidly and mass education is expanding more and more. However, still one of the big problems in Uganda is that many students drop out of primary school after a few years and only a small portion of the population completes secondary school, and as little as 4% attend tertiary institutions like universities. The Ugandan school curriculum is now revised every 5 to 7 years by the government, and the National Curriculum Development Centre of the Ministry of Education and Sports is endeavored to make the curriculum-building process more inclusive. Still, the quality of education has not improved as rapidly as the increase in access to schooling. For instance, the teachers are not always trained according to the newest curriculums, and educational infrastructure (safe schools, desks, sanitation, books, etc.) remain scarcer than is ideal.

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

Ugandan Demographics - Rich and Diverse or Complex and Convulted?

In our podcast, we talk a lot about Uganda’s ethnic and tribal diversity. But what do these categories even mean? Let’s see if we can break it down somewhat:

categories even mean? Let’s see if we can break it down somewhat:

Ethnic Group

People belonging to one ethnic group share the same religious, linguistic, and cultural identity, as well as a common ancestry or historical background. They are not bound to one area of living.

Tribal Group

A tribe consists of a set of related families with similar tastes, ideology, religious and dialectic identity. They live together in one place.

*

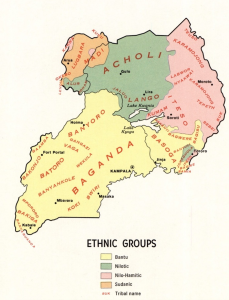

Uganda’s inhabitants are composed of three to four different ethnic groups. They are believed to have migrated from different places and then settled in different locations around the country, as well as across the borders to the neighboring countries (though keep in mind that modern borders were drawn by colonial forces)

The largest ethnic group in Uganda, the Bantu, are spread throughout Central, Southern, Eastern Africa, and Southeast Africa. Consisting of about 400 distinct tribal groups native to 24 countries, within this category several hundred Bantu (appr. 400-700, depending on the definition of ‘dialect’ and ‘language’) languages are spoken. The Bantu are divided into several tribal groups, the largest being the Baganda, whose population consists of over 10 million people (as of 2019). Other tribal groups are the Basoga, Bagwere, Banyoro, Bayankole, Bakiga, Batooro, Bamasaba, Basamia, Bakonjo, Baamba, Baruuli, Banyole, Bafumbira, and the Bagungu, all of whom have their unique languages and dialects. The languages with the largest amount of speakers within the Bantu peoples of Uganda are Luganda, Runyankore, Lusoga, Rukiga, Masaba, Runyoro, Konjo, Rutooro, Lugwere, Kinyarwanda, Samia, Ruuli, Talinga Bwisi, Gungu, Amba, and Singa. The lingua franca between the Bantu peoples of Africa is Swahili.

The Nilotic peoples (also: Luo) originate from the Nile area and are spread mainly throughout Eastern African countries. Inside Uganda, they have mainly settled in the North. Tribes within the ethnic group include the Langi, Acholi, Alur, Padhola, Lulya, and the Jonam. The Nilotic languages are linguistically divided into Eastern, Southern, and Western Nilotic languages, each of which are spoken by Nilotic populations in Uganda. One of the larger tribal groups within the Nilotic peoples are the Acholi, which make up about 2 million of Uganda’s population (as of 2014). Their dialect is a Western Nilotic language, named Luo (Lwo). The Nilo Hamites (also: Central Sudanic peoples) are mainly located in the Eastern part of Uganda. Their tribes include the Karimojong, Iteso, Langi, Kumam, and the Kakwa.

The Sudanic peoples inhabit the northwest of Uganda.

Within Ugandan tribes, there are quite some cultural differences, including certain ceremonies, dances, staple foods, economic activities, dress, art, religions, and – what’s most important regarding the content of our podcast – languages. As we discus in the podcast, the fact that many languages are spoken throughout Uganda – and finding a common language is not always possible – creates challenges regarding the connection between the Ugandan peoples, as well as creating a common sense of identity. There have been attempts to instate Swahili as the lingua franca in Uganda and surroundings, and although it has not been enforced yet, it might be a good solution to promote better communication among the peoples of East Africa and to elevate the status of Swahili as an international language.

Regional Identity

A regional identity presumes the common characteristics and shared identity of numerous nations and ethnicities in a specific region.

The formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) led to a strengthened identification between African leaders towards each other. It also supported the rise of a Pan-African identity that transcended the boundaries of the borders made by colonists. People mainly identified through their common oppression by Europeans through the implements of slavery, racism, and colonization. A shared identity often holds a shared history, and common obstacles that can be overcome together.

The OAU maintained a strong commitment to respecting state sovereignty and the sanctity of the existing borders. The successor of the OAU is the African Union (AU), which focused more on the African people than on the states. The AU declared its right to intervene in ‘grave circumstances’ with the Assembly’s approval, which shows a movement towards collective governance.

In East Africa, serious proposals have been considered for joining together as a single sovereign state. In 1967, the East African Community (EAC) was established by Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. It fell apart in 1977 due to ideological differences and conflicting economic interests among the state leaders but was revived in 1999. In 2007, Burundi and Rwanda, and in 2016, the Republic of South Sudan became full members of the EAC. This year, the Democratic Republic of Congo also became a member. The main goal of the EAC is to expand and deepen economic, political, social, and cultural cooperation. In the long term, a federal state is to be created through the creation of a customs union, a common market, and a common currency. There’s a common court, the East African Court of Justice and a parliamentary assembly, the East African Legislative Assembly. Since 2010, the EAC also has a shared anthem.

Image source: https://rosebellkagumire.com/2009/09/10/my-tribe-is-my-pain/

Image source: https://i.pinimg.com/originals/b5/79/d7/b579d7249f09be3ab5810d641d9b9be2.jpg

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................

Suggested Further Reading

Non-academic

Pamooja Movement Instagram account: https://www.instagram.com/eapamooja/

Pamooja Movement Website: https://parliamentwatch.ug/blogs/ugandas-new-curriculum-for-lower-secondary-will-it-meet-learners-skill-needs/

Ugandan Proverbs: https://www.motivation.africa/30-ugandan-proverbs-and-their-meanings.html

Academic

Greene, L., Creating a Nation Without a Past. Secondary-School Curricula and the Teaching of National History in Uganda, in: M. J. Bellino & J.H. Williams (Eds.), (Re)Constructing Memory: Education, Identity, and Conflict.

Anderson, Imagined Communities, (London, 1983).

D.Van Hulle, and J. Leerssen (eds), Editing the Nation’s Memory: Textual Scholarship and Nation- building in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Amsterdam, 2008).

E Charles, “Decolonizing the curriculum,” Insights, Vol. 32:24, (2019) pp. 1–7.

Hobsbawm and T. O. Ranger (eds), The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge, 1983).

Nyoni, “Decolonising the higher education curriculum: An analysis of African intellectual readiness to break the chains of a colonial caged mentality”, Transformation in Higher Education, Vol. 4, (2014), p.69.

Gervits, ‘Historicism, Nationalism, and Museum Architecture in Russia from the Nineteenth to the Turn of the Twentieth Century’, Visual Resources, Vol. 27, (2011), pp. 32–47.

Takako, “History Education and Identity Formation: A Case Study of Uganda” (2011), CMC Senior Theses. Paper

Muyanda-Mutebi, “An Analysis of the Primary Curriculum in Uganda including a Framework for a Primary Education Curriculum Renewal“, UNESCO.

R. Porter, and M. Teich (eds), Romanticism in National Context (Cambridge, 1988).

********

Text and Podcast by Klara de Groot & Maya Thomas