The Hadza people in Tanzania are one of the last hunter-gatherer populations left in the world. They live by foraging for wild foods, therefore they take no part in agriculture or animal husbandry. They are therefore also part of the few populations that still engage in the lifestyle of our ancestors prior to the introduction of agriculture and industrialisation. Records of the Hadza take us back to before the 1930s (Marlowe, 2010).

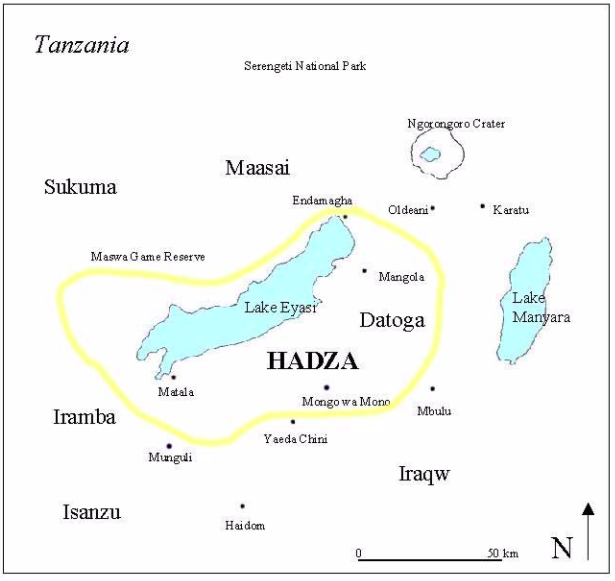

It is roughly estimated that there are 1,000 Hadza left. They are situated near Lake Eyasi (or Balangida in their language), in northern Tanzania, near the Karatu district or Arusha region. They occupy about 4,000 km2. They are spread around the west and east of the lake, but both groups move around freely.

Frank Marlowe, (2002)

The Hadza language is known as Hadzane, and is known as a click language. It is a small language and due to the low amount of speakers, it is considered extremely vulnerable.

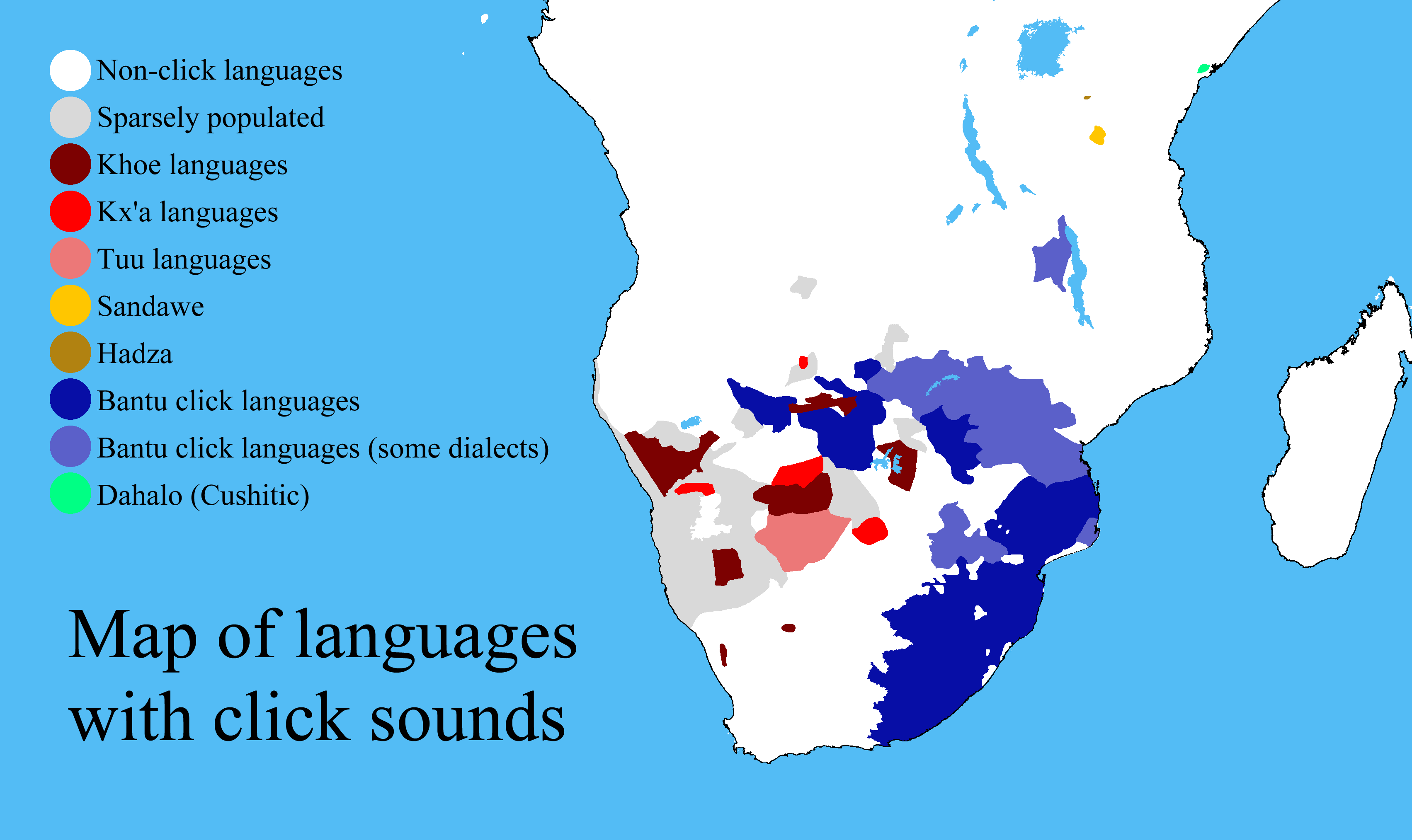

Recent research indicates the Hadza language is a linguistic isolate, meaning it has no relation to any immediate neighbours and that the Hadza have been able to maintain a good deal of autonomy (Marlowe, 2002). The map to your right indicates where the click languages are mostly spoken in Africa. This map also shows how the Hadza are a bit further away from similar languages. It is 1/3 East African click languages - the only three languages outside of southern Africa to have clicks (Sands, Maddieson and Ladefoged, 1996).

Recently, almost all Hadza speak fluent Swahili as their second language. Hadzane has also borrowed some words from Swahili and other nearby languages, but the growing knowledge of Swahili amongst the Hadza people is fairly recent (Marlowe, 2002).

Researchers think that the Hadza speech community will remain stable as long as they are able to continue living their traditional life (Legere, 2006).

What does the language look like?

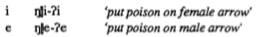

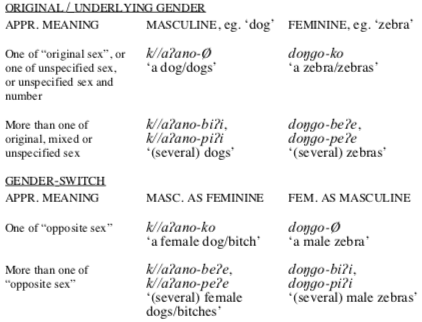

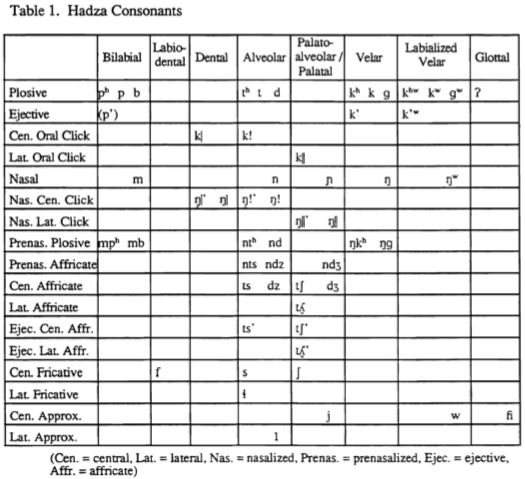

To the right you can see some examples of what the language looks like. As you can see, we are not even able to write Hadzane as our keyboards and our own language structure does not recognize it. The click aspect is of course also a very unique addition to the language that is hard to describe.

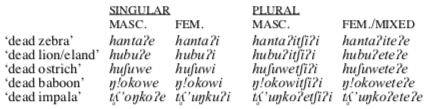

In addition, as mentioned above the Hadza language is formed around their lifestyle, and they have very specific words in their language that relate to their lifestyle and what is important to their lifestyle - such as specific dead animals, or putting poison on an arrow.

Hunters and Gatherers

The latest linguistic work points to clicks as having deep roots, originating at the limits of linguistic analysis more than 10,000 years ago. Genetic data even suggests that click-speaking populations go back to common human ancestors perhaps more than 50,000 years ago (Knight et al, 2003). The deep genetic divergence among the click-speaking peoples of Africa might indicate that a lot of these languages developed separately from each other. A possible explanation would be that click constituted an advantage during hunting in certain environments. The Hadza have about a dozen specific words for dead animals, which are used to announce a kill. This is an exemplifying case of how language can relate to ways of living.

Tourism: Threat or Blessing?

The Hadza hunter-gatherers have been engaging with tourism since the 1990s. Tourists visit the camps to witness their life, to go hunting, shooting arrows, enjoying Hadza dance, and finally buy hand-made souvenirs. This provides the Hadza with a means of income, which is argued to be important for their survival as land for hunting gets more scarce. Their nomadic lifestyle means that they have agency in joining or escaping from tourism at their own initiative. However, tourism also brings along with it risks for the continuation of the Hadza language. For example, they are more directly exposed to other languages. Furthermore, the necessary tourism infrastructure can lead to spatial divides in the Hadza territory.

In the last several decades, the Hadza have lost 90% of their ancestral lands. Their homeland which 30 years ago had enough wildlife to rival any National Park, now holds only fragments of past herds. And when the wildlife is gone, so too will be the Hadza culture and language.

References:

Knight, A. et al., 2003. African y chromosome and mtdna divergence provides insight into the history of click languages. Current Biology, 13(6), pp.464–473.

Legère, K., 2006. Language endangerment in Tanzania: Identifying and maintaining endangered languages. South African Journal of African Languages, 26(3), pp.99–112.

Frank Marlowe, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University

2002. In Ethnicity, Hunter-Gatherers, and the “Other”: Association or Assimilation in Africa, Sue Kent (Ed.) Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp 247-275.

Marlowe, F., 2010. The Hadza: Hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sands, B., Maddieson, I. and Ladefoged, P., 1996. The phonetic structures of Hadza. Studies in African Linguistics, 25(2), pp.171-204.

Yatsuka, H., 2017. Attitude of the Hadza hunter-gatherers toward tourism in Tanzania: Journal of African Studies, 2017(92), pp.27–41.