Africa is shaped like a gun, and the Congo is its trigger. If that explosive trigger bursts, the whole of Africa will explode.

Frantz Fanon

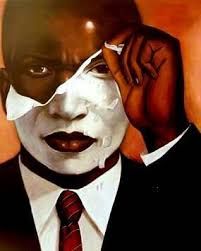

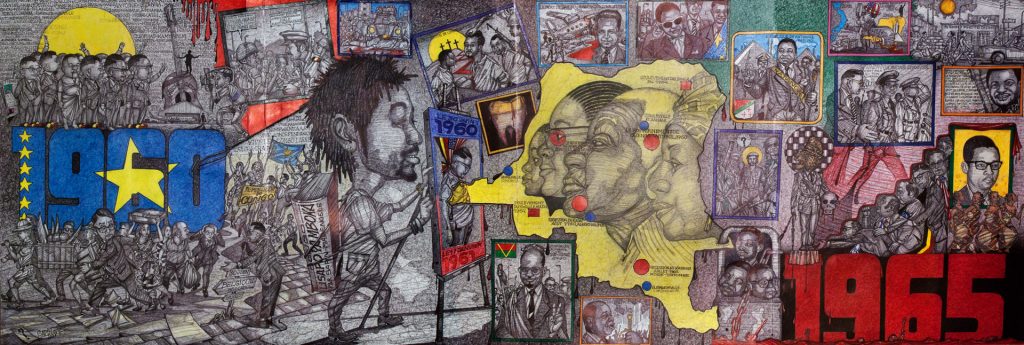

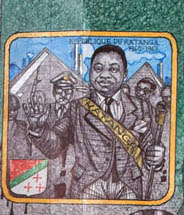

The quote above, made by Frantz Fanon at the start of the Congo Crisis, encaptures the importance of Congo and its crisis in the wider context of the decolonisation process that spread across the African continent during the 1960s. Through analysing Sapin Makengele’s Congo Crisis painting, as found above, this project seeks to understand the Congo Crisis through conceptualising Fanon’s ideas on the psychology of colonisation amongst and how this mental stranglehold significantly affected the relationship between the colonised and their coloniser, even after the so called “decolonisation” process has finished which in the case of this essay will focus on the Congo following its independence in 1960. This project will attempt to do this by decrypting Sapin’s description of Katanga’s attempted succession under the leadership of Moïse Tshombe, not only a prominent figure in the Congo Crisis but also understood to be one of the key perpetrators behind the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first Prime Minister following independence from Belgium in 1960, and great friend of Fanon.

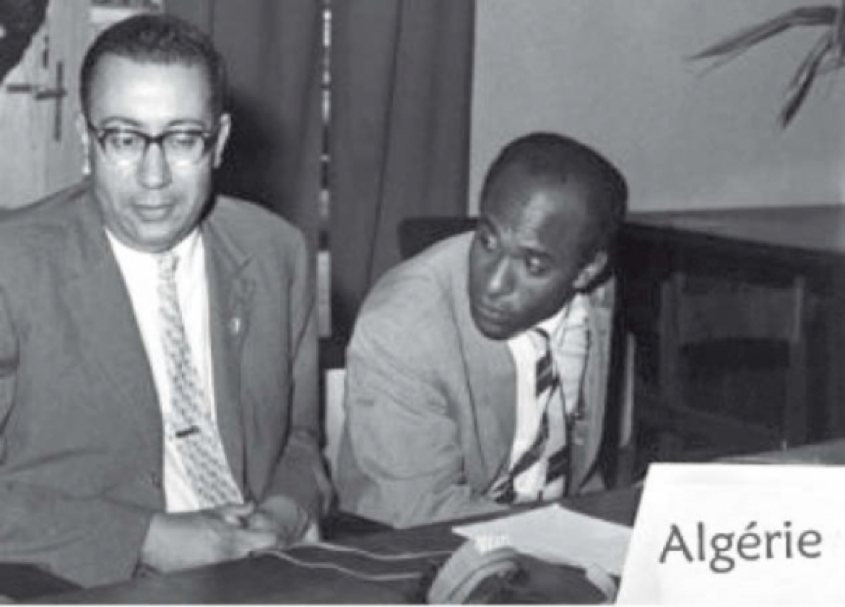

Fanon plays a peculiar role in the Congo Crisis and his somewhat unique circumstance makes him a great outlook when viewing the Congo Crisis, in addition to Sapin’s painting, given that Fanon’s philosophical and critical theory produced on the effects of colonisation and the need to decolonise in a particular manner presents a different viewpoint on the events that took place in Congo following its independence in 1960. Moreover, his affiliation and relationship to both Patrice Lumumba and Algeria provided me with a great vantage point to view the crisis from a specific lens which shall be shown throughout the project in my analysis and historiography of both the Katanga succession attempt and Algeria’s involvement in the Congo Crisis and the reasonings behind why this decision was taken, with the aid of archived primary sources in the guise of multimedia footage from the 60s.

Moïse Tshombe also plays a central figure in this project, as the second major aim of this project is to explore and highlight Algeria’s involvement in the Congo Crisis as an external force battling on the side of the newly independent Congo, as opposed to other external forces such as Belgium and the USA, who acted as chief instigators in the formation of the crisis, as depicted by Sapin himself in his painting. The role of Algeria is an important one for various reasons, given that the important relationship held between these two African states was actually forged before the Congo Crisis began in 1960, with Fanon himself acting as a revolutionary and intellectual broker between the two countries as seen in the archived video footage found within this project. This forged allegiance would not disband following the removal of Lumumba and the death of Fanon, but rather through the continual promotion of both Third-Worldism and Pan-Africanism, Algeria declared it an abomination to “betray” its wounded brother in its hour of need and rather brought it upon themselves to hold Tshombe accountable for his “crime against humanity and Africa” regarding his involvement in the assassination of Lumumba by arresting and then further refusing to hand over Tshombe to those Congolese officials sent by Mobutu, where Tshombe would spend his final days in prison in Algiers where he would later die in 1969.

Below one can find the various pieces that make up this project, each highlighting the critical junctures in the historiography of the Congo Crisis, whilst also presenting the strong case for art being used as an alternative means for critical historiography to take place in an effort to revolutionise the way we see and study history across the globe, whilst also attempting to make it more accessible to all.

Hyperlinked articles below (click in image)