The Fourth Estate is under attack, or so says conventional wisdom in the era of populist backlash across the Western world. The cries of ‘fake news’ come from all parts of society – from the ‘leader of the free world’ to the average citizen grumbling about the ‘mainstream media’. On the African continent, after the liberalisation of press freedom in the 1990s it seems as if that freedom is on the retreat – and that the curtailing of said freedom is being welcomed by Africans.

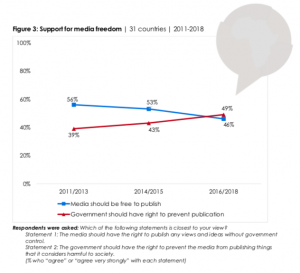

In their frequent surveys Afrobarometer gathers the opinions of those on the continent on a whole range of issues from LGBT rights to Governance. One of their common surveys seeks to analyse African citizens’ attitudes towards freedom of the press. The Afrobarometer findings can be perceived as concerning. “Popular support for media freedom continues to decline, dropping to below half (47%) of respondents across 34 countries. More Africans (49%) now say that government’s should have the right to prevent publications they consider harmful.” It would be helpful if Afrobarometer went further at this point to seek out what citizens considered to be ‘harmful’ – where people decide to draw the line on acceptable and harmful would be a helpful slice of extra information on attitudes towards press freedom on the continent.

Nevertheless, some of the numbers for individual countries are alarming – in Senegal only 18% of people surveyed agreed with the statement that “the media should have the right to publish any views and ideas without government control”, a trend that was reflected across the rest of Western Africa where as a whole only 40% agreed with this statement. Across the countries surveyed as well, there has been a swing towards wanting greater limits on press freedom – between 2011 and 2018 there has been on average a decrease of 10% in supporting press freedom. The biggest negative swings coming in Tanzania (-33%), Cabo Verde (-27%) and Uganda (-21%).

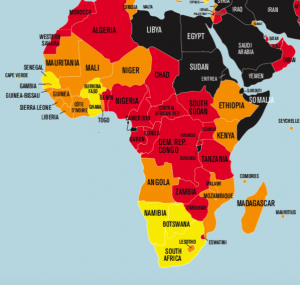

The Afrobarometer survey paints a picture then, of a continent where citizens are worried about the excesses of the freedom of press and seeking to curtail those freedoms, which in turn suggests that press freedom on the African continent is wildly out of control and the excesses need to be reined in. When looking at the Press Freedom Index created by Reporters Sans Frontieres however, that impression of a wildly liberalised press sector quickly vanishes, and prompts questions. The RSF carries out a questionnaire, that is appropriately translated, that seeks to analyse press freedom according to pluralism, media independence, environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency and infrastructure. The final indicator is ‘abuses’ in which a dedicated team in the country will tally up the number of ‘abuses’ that journalists and media organisations face – including violent abuse. The RSF’s index is comprehensive and quantitative and lists the wide number of abuses journalists have faced in differing African countries, from Mauritania where RSF-backed bloggers are jailed to Mozambique where coverage of violence is banned. Overall the RSF’s picture of press-freedom in Africa is “problematic” (Orange) to a “very bad situation” (red).

How then do we square these seemingly contradictory phenomena – the attitudes towards press freedom and the seeming reality of press freedom? Certainly one aspect we can look at is the dynamics of class in its relation to press-freedom. The RSF’s questionnaire is comprehensive and well-done but it only targets a narrow slice of society; “media professionals, lawyers and sociologists” are asked to complete it – these are not ordinary members of society but those who are near the apex of it. Indeed, the aforementioned Afrobarometer survey found that across the continent the biggest signifier of whether a citizen wanted greater government control of press freedom was “no secondary education”.

The picture is muddled and confusing, and we will have to wait until the next Afrobarometer survey on this issue to see whether the trend towards curtailing press freedom is permanent or a temporary blip. What we do know for certain however, is that just as in other parts of the world citizens in society are asking how much freedom is desirable, especially when it comes to The Fourth Estate.

References:

J. Conroy-Krutz and J. Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny, “How Free is Too Free? Across Africa, media freedom is on the defensive”, Afrobarometer Policy Paper, no. 56, May 2019 https://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Policy%20papers/ab_r7_policypaperno56_support_for_media_freedom_declines_across_africa_1.pdf

Reporters Sans Frontieres, “The World Press Freedom Index”, 2020, https://rsf.org/en/world-press-freedom-index

Mirjam de Bruijn

October 14, 2020 (16:51)

I like this analysis in which you confront data sets, that are both gathered in a different way. The two indicate tendencies that are both worrying and indeed somehow contradictory. As such you show that confronting data sets can lead to the formulation of interesting research questions that might help you formulate and develop more qualitatively oriented research to go behind the statistics.