This summer, the overturning of Roe v Wade, the landmark decision which safeguarded the right to abortion in many US states, displayed a devastating blow to the women’s liberation struggle. It is in such moments that we need to remember that the sexual and reproductive rights of women are in a constant state of contestation globally. I, therefore, want to bring attention to Senegal.

Senegal harbours one of the most restrictive anti-abortion regimes in Africa, prohibiting abortion even in the most extreme cases, like rape and incest, and harshly criminalizing both the women seeking abortions as well as the healthcare workers providing them. One-third of the female prison population in Senegal is made up of women convicted for abortions or – infanticide (Moseson et. al. 2019: 2015). Infanticide is what I want to focus on here. Newborns, willfully neglected, abandoned in dumps or railways, or intentionally killed. It is too frequent of an occurrence in Senegal, as anywhere else in the world, but one study sought to link the cases of Senegalese infanticide, to the restrictive anti-abortion policy of the country.

As the 2019 study by Moseson et.al. points out, the phenomenon of infanticide exists everywhere, it is not bound to a specific culture, or point in history. And it occurs for various reasons. The first part of the study explores motivations for infanticide across different social contexts, most of which boil down to the inability to feed a(nother) child or cultural stigma. Stigma, for example in the case of children born out of wedlock, should not be underestimated as a driving force. It can come with material consequences for the mother, in the form of ostracization from her family or community.

By its very nature, this inquiry is interdisciplinary. It links policy and the judiciary, to a socio-cultural analysis, all centred around what is essentially a public health issue. While it cannot necessarily be said that the study operates through a feminist theoretical lens, it is concerned with reproductive rights which is a common objective of feminist movements. In addition to that, it touches upon the impact of gender norms, specifically the stigma about female sexuality and the exclusion of women from the political arena. This merging of fields is furthermore reflected in the study’s multidisciplinary authors. Amongst them, we find, an epidemiologist specialising in reproductive health, an anthropologist, a jurist and the coordinator of a Senegalese abortion rights NGO.

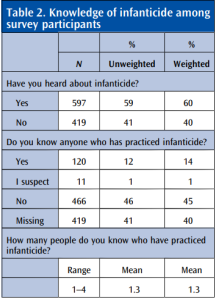

Due to a lack of available data on frequencies and means of infanticides, their research includes a quantitative survey, which seeks to m occurrences and means of the practice. As the table below depicts, 40% of the participants were familiar with the concept and around 14% personally know a person who has committed it themselves. But the survey questions expand beyond infanticide. Participants were also asked about their awareness of the Senegalese anti-abortion law, and if they personally had to seek an abortion in the past. For this survey, a target population comprised of four different regions in Senegal has been sampled, to portray the diversity of social settings in the country.

From the subsample of interview participants, the researchers selected people who have indicated experience, or knowledge of infanticides in their environments. As in the survey, the researchers did not only ask about infanticides in the interviews but also about community norms, pregnancy and abortion. The participants described how they encountered cases of infanticide, through the discovery of a deceased infant, through rumours, or by deducting it from the apparent absence of a baby after a woman had been noticeably pregnant.

The interviewees described the different situations the women who had practised infanticide had found themselves in and they named as their possible motivations, economic hardships, social stigma, if it was an unmarried woman, and most importantly the inaccessibility of abortion. In some cases, infanticide was committed by a woman who underwent repeated unsuccessful abortion attempts, only having access to unsafe, ineffective and illegal pathways. As the interviewees reported many women sought out abortion care, at the risk of their own health, failing nonetheless. As one participant stated:

‘“The laws are strict, especially in case of rape and incest; if abortion was allowed, there would be no more infanticide” (age 36, Dakar Gueule Tapée) (ibid: 210)’

The data proves the study’s original hypothesis: That the problem of infanticides in Senegal is a direct consequence of the strict abortion regime. This knowledge is relevant beyond the scope of academic study. The report goes on to explain that the findings will be used by the Senegalese Taskforce on Safe Abortion to demonstrate to legislators how urgent the need for safe abortions is. The authors explain how difficult it is to even bring the issue to the table of those conference rooms in which legislators ponder over the fate of Senegalese women. Not only because of those who oppose it for religious reasons, or because they hold beliefs about modesty, family values, or a woman’s place. Also because of those who simply don’t care. Who think this is just a woman’s issue. A non-priority demand.

The authors of this study used transdisciplinary research, expanding beyond the merely academic, to gather knowledge that has the potential to change something in the lives of Senegalese women who need and deserve reproductive autonomy.