Criteria for African film selection at Dutch film festivals

With the background knowledge that you as a reader have acquired in the first two blogs of African Cinema and LIFF and IFFR, what do the curators of these two festivals have to say about their selection?; An analysis of interviews with Nick, Peter, Elvire and Annachiara.

The first question we asked our interviewees is what they think ‘African film’ is. According to Peter, African film is film made by an African. Location does not matter, since people from the diaspora are also African. Furthermore, Peter does make a distinction between North-Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. Annachiara argues that the origin of the film does not necessarily say something about the authenticity of the film. Themes are more important than the place of origin. Nick and Elvire (see audio below) had similar thoughts; there is no such thing as one African film, and it is not viable to speak about one African film. Hence, you cannot define African film as one genre.

However, there might be something that unites them, but Nick cannot really put his finger on it.

Peter thinks that African filmmakers often want to say something about Africa, about their reality. This includes socio-political critique. Elvira has a similar vision, where she thinks African filmmakers want to tackle a specific aspect of what they see as a problem. Nick says that all films have a certain element of socio-political critique, but that this is more overt in African films. These films, the ones that contain socio-political critique, are often the films that travel abroad, and are shown at international film festivals.

What is important in film selections is that a film fits the theme of the particular festival (that year), it is appealing to the broad audience, fit in the budget, it has to be a relatively new film and has to be a certain relevancy. However, most importantly, film selection is dependent on the availability of film.

African cinema is underrepresented outside of Africa. Without film festivals, a lot of films would remain unknown. Film festivals give a stage to independent films and underrepresented films. According to Nick and Peter, without international film festivals, African movies would not be shown abroad. Peter states that because there is societal critique present in these African films, it can get censored in the film maker’s country. African independent movies are dependent on international film festivals.

The IFFR specifically shows films from parts of the world of which they think are underrepresented in cinema. Peter states that he wants to give a stage to those countries and film makers that rarely come to light. Showing African films in their film selection gives African film makers and their country a ‘voice’. Nick states that the LIFF is not focused on showing ‘movies that matter’. They do however help film makers get audiences. They show independent cinema from all around.

“The filmfestival has a long tradition to give special attention to areas that are underrepresented in our opinion. The filmfestival has formerly also supported African filmmakers in realizing their work.”

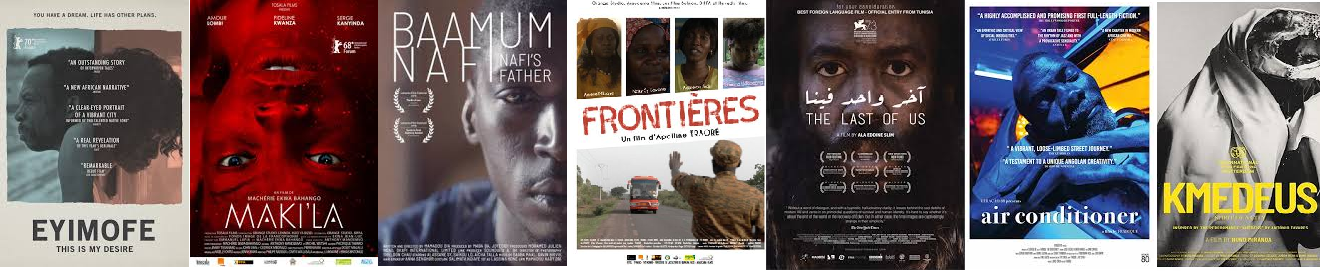

In order to get African films, Peter says that he would often go to the African continent to buy films, or to have film collectives make films for the festival. He argues that the infrastructure to get films abroad is weak, and thus this is a solution. Nick states that he experienced some difficulty in obtaining the films for the Africa2020 film festival program, specifically regarding communication with the African filmmakers and transport of film. When selecting movies, the two film festivals create a shortlist that contain films that fit in the theme of the year and with the identity of the film festival, and from there they choose the films that meet the other criteria the best.

We asked them what they value most in African films; if it was academic or ideological value, artistic value or entertainment value. Elvire wants to show films that reflect current developments within Africa that are relevant, but in the end she selects what she thinks is interesting to show. For both Elvire and Nick the artistic value is the most important. Nick states that they do not avoid socio-political films, but also do not actively seek them out. If a film has entertainment value, academic value, but lacks the artistic value, it is likely it will be rejected. Peter argues that for the IFFR the academic value is predominant. Socio-political critique is important to show, since he thinks that it will not be shown elsewhere. Entertainment is important too, but not the most important in his film selection.

Elvire states that one’s background has an influence in film selection. You cannot erase your own personal interest .In the end you select the films you like. Nick has a background in film, and hence looks more at the aesthetics of the film, and the artistic value. As was mentioned in the literature, the curators background will inevitably affect film selection.

Does film selection of film festivals give an accurate image of Africa and African cinema then? When it comes to African cinema, Nick argues that the films that get here, might not be an accurate representation of African cinema. African cinema in the Netherlands is (not yet) mainstream, and there is a lack of availability, and, as mentioned before, the films that do travel here are mostly the ones with the socio-political critique. Entertainment films are generally made for African audiences, and hence difficult to show here. Thus, African cinema outside of Africa is underrepresented. It would be a more accurate representation if more local ‘entertainment’ films would be included. Nick also states that the transport of films and communication are however improving, and hence African films are already getting more traction.

When it comes to an accurate representation of Africa through film selection, Peter argues that they seek out the socio-political films, because they want to show films that represent Africa. He also mentions that it is also possible that African filmmakers who make a movie for an international film festival, could create what they think the audience of the film festival wants to see, and this thus can result in stereotypical movies. Furthermore, he states that audiences generally like to see stereotypically ‘exotic’ films. Film festivals can feed into this exoticism by showing an exotic African film. The only way to give an accurate image is to be aware and reflexive of that and to create balance for a more accurate image. Elvire says that to create a more accurate image of Africa through film selection, one should include more popular culture films, as it will give a more holistic view of a country’s cultural scene.

“It is one of the most important jobs you have as film festival, that with the choices you make you create an image of a community to the outside world. People are curious about the rest of the world, which often creates a romanticised image. As film festival you can ‘feed’ this exoticism by selecting films that confirm that image. It is exciting to show a film on withcraft, which is depicted in a small village. Next to this, it is important to show a film that has the big city as location.”

It differs per film festival if they actively seek out the socio-political critical films, but in the end it is mostly the these African films that reach international film festivals. Films that are made for local African audiences tend to have less critique, but again, these are difficult to obtain. This, and the fact that film selection is also a personal choice, could perpetuate a certain image of African cinema and the African continent, but not always on purpose. It is however important to be aware of this. However, as Elvira states, there is a trend of a rising demand for more ‘entertainment’ films, which is why Nollywood films are increasingly shown abroad. African cinema and African representation through cinema is, and has been a changing field since the 19th century.

It differs per film festival if they actively seek out the socio-political critical films, but in the end it is mostly the these African films that reach international film festivals. Films that are made for local African audiences tend to have less critique, but again, these are difficult to obtain. This, and the fact that film selection is also a personal choice, could perpetuate a certain image of African cinema and the African continent, but not always on purpose. It is however important to be aware of this. However, as Elvira states, there is a trend of a rising demand for more ‘entertainment’ films, which is why Nollywood films are increasingly shown abroad. African cinema and African representation through cinema is, and has been a changing field since the 19th century.

Let’s see what the future holds.