Aminata Estelle Diouf (University of Cologne)

Introduction

In the scope of the Decentering Epistemologies project and my affiliation to the “heritage” subgroup, I decided to revisit Cologne’s ethnological museum, the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum – Cultures of the World (“RJM”). In order to tie together the topic of decentering epistemologies and wellbeing with the heritage of museums and situate my research within a German context, I decided to focus my article on the critical examination of the colonial continuities and legacies of European ethnological museums, the RJM being at the center of this case study. I am quite familiar with the museum, as I have visited the permanent exhibition several times recreationally and I worked for the museum during the RESIST! exhibition (Spring 2021 – January 2022) as a live-speaker, a new arts education and museum’s pedagogy concept introduced by the museum to create a dialog with the public. In recent years, the museum has shifted its thematic focus, emphasizing postcolonial, decolonial and intersectional perspectives and introducing new formats that engage with critical issues such as colonial history, the colonial legacies of museums as well as restitution. This is a novum in the German museal landscape, especially for ethnological museums, which have played a crucial role in forming and fortifying racialized and racist notions of otherness and exoticism of non-European cultures.

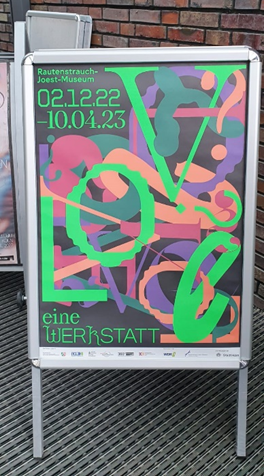

I went to visit the RJM’s most recent temporary exhibition LOVE?, which focused on modern ideations of love and how it is tied to asymmetries of power in relation to capitalism and colonialism. The exhibition ran from 2. December 2022 until April 10th 2023.

Background of the Museum

The Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum was first established in 1901, moving into a compound in the Southern district of the city in 1906. It was founded by Wilhelm Joest, the son of the sugar manufacturer, who is depicted as a so-called “world traveller” or “explorer” on the museum website [1]. Joest bequeathed his private collection consisting of 33,500 objects to his sister Adele Rautenstrauch-Joest, who initiated the construction of the museum. My first thought, when looking into how the museum self-represents its own history was that the depiction felt rather romanticized. Much of the cultural artefacts and wealth accumulated in the context of colonialism was based on the violent European expansion and global colonization processes, powered by the capital of European empires and industrialists and the forced labor of peoples from Africa, the Americas and Asia. Through strategies of dispossession and the conduction of punitive expeditions against colonized populations, many looted artefacts began to circulate the European art market and found their way into ethnological collections.

In its online self-presentation, the museum only alludes to its colonial past in a short paragraph emphasizing that Cologne was considered a “stronghold of the German colonial movement” [2] at the time of European colonization and that considerable parts of the collection were acquired before the First World War. There is no word, however, about how the objects of the collection were acquired or how those statements relate to the RJM’s founders.

The collection consists of approx. 65,000 exhibits from Oceania, Africa, Asia and America, a photo archive with over 100,000 photographs and a library. After a fifteen-year planning phase, the RJM opened at a new location near Neumarkt in 2010, displaying a so-called “comparative cultural exhibition.” Through cultural universalisms, the so-called “theme parcours,” the permanent exhibition highlights similarities and differences across different world cultures, using narratives such as “fashion,” “death,” and “beliefs”.

Many objects behind display cases are provided with minimal description or information on their cultural context and are clustered with similar-looking objects from other geographical regions. I have seen similar approaches in other German and European ethnological museums and feel, that this approach creates an image of an exotic other that insufficiently portrays the cultural realities and historical developments of the cultures that are referenced.

Discourse

While activists, researchers, political actors of formerly colonized nations as well as grassroots organizations have long been calling for the decolonization of ethnological museums and the return of looted artifacts and art treasures, only in recent years, have these efforts and discourses on the legacy of ethnological museums in Europe reached broader public spaces and media visibility, with topics such as restitution as well as the colonial entanglements of institutions such as the Humboldt Forum in Germany, the British Museum in the UK and Africa Museum in Brussels now being openly criticized. Much of the looted art in the depots and archives of these museums have not seen the light of day in decades or even ever. How can this be? Many of these institutions were established during the colonial period as instruments to display colonial wealth, spread ideologies of the supremacy of Western civilization and legitimize Euro-American rule.

With its last directorial shift, the RJM has been in a process of structural change and has made an effort to critically examine and decolonize the institution and initiate a process of restitution. So far, these efforts have materialized in the subtle changes of the museum’s permanent exhibition, which has begun to incorporate anti-racist and anti-colonial perspectives into the museum’s permanent exhibition, such as artist Nando Nkrumah’s installation on structural racism or the restitution of the so-called Benin Bronzes, artefacts looted by British forces during a punitive expedition in Benin in 1897 and acquired by the collection’s founder.

Resist

This perspectival shift has also been implemented in the recent temporary exhibitions: the first being RESIST! – the Art of Resistance (2021-2022), which addressed 500 years of violent European colonial oppression, anti- and decolonial resistance, and self-empowerment in diverse local and global, historical and contemporary contexts and was conceived to highlight the voices and perspectives of the colonized and their descendants. “Resistance” served conceptually as the superstructure of the participatory, multimedia and experimental exhibition. In addition to the physical exhibition, which linked multimedia installations with photography, film, visual and auditory art to artifacts from the museum’s collection, there were various workshop and event formats such as the Cinema RESIST! and projects with local youth and cultural associations and activist groups. This involvement of local actors from civil society was an important focus of the implementation.

LOVE?

The exhibition LOVE? could be seen as a follow-up or conceptual continuation of RESIST!, again making space for marginalized cultural actors that do not typically take up space in these types of institutions and aiming at critically examining and decentering the hegemony of Western epistemology by displaying positions and perspectives that are often invisible. Thematically the exhibition deconstructs modern conceptions of love and looks at how they are tied to colonialism and how they connect to or create normative notions of gender, sexuality and race. LOVE? deviated from the typical exhibition format and was less of a frontal display of art and exhibits, but was rather intended as a collective, participatory open space, that tries to tackle the topic in a dialog with the public and different local activists, researchers and artists. The exhibition had two areas within the building: The first room, “the kitchen” functioned as a transformative and open space used by different cultural actors and activist groups for interventions, workshops, and performances.

The main exhibition space featured artworks and exhibits in different formats ranging from photography, installations and carpets, to sculptures, and objects from the museum’s depot. Another connector to RESIST! was the exhibition’s growing library, extended with a reading and listening corner, where one could retreat to read or listen to podcasts dealing with love through different intersectional and critical lenses such as the Asian diaspora-centered series Rice & Shine or the German-Tamil podcast Acca Pillai. Other works featured were i.e. the video installation by artist Barbara Stephenson, who thematizes how the weight of social expectations affects women, a photo book on the life of Audre Lorde and photo series by Haitian Jean-Ulrick Désert, which reads as a critique of Robert Mapplethorpe’s exoticizing gaze of the Black male body.

Visitors pass two questions on the wall of the main exhibition space when walking through the room: “What could love mean?” and “What do love and colonialism have to do with each other?” I visited the exhibition twice, each time engaging with these two questions and trying to keep in mind the multitude of ways in which knowledge and well-being relate to each other and influence one another depending on the different positionalities and locationalities within or outside of hegemony. The co-existence of knowledge and well-being in a space with such a violent legacy felt like an impossibility.

During my first visit, I was able to participate in a guided tour and group discussion with a group of activists and artists of color, who had collaborated with the museum for the exhibition. During our talk, we discussed the power asymmetries within these types of cultural institutions, the topic of love, the politics of restitution and aspects of empowerment, retraumatization within these spaces for marginalized collaborators as well as visitors of color, which in many ways reflected my own relationship with the institution and experiences of working there. One line from a song by musician Rihanna sums up our realization during the discussion quite well: “we found love in a hopeless place.” But maybe not in the way that we had individually expected, or the museum expected with this new approach to the practice of exhibiting and curating: while, for cultural actors of color, such as myself, collaborating with these types of spaces is an attempt to give our own perspectives and social causes more visibility, it also means that we are subjecting ourselves to different forms of violence, be it structural violence, historical violence, racialized/sexualized violence, or the violence of spectacle. It is love that brings us into these spaces, the love that we have for the people that share our struggles, the hope that we can make an impact by taking up space. As one of the artists pointed out during the discussion, this is a tedious and exhausting process. On the one hand, it feels like a positive change that those typically excluded from these spaces are invited in, on the other hand, they are constantly exposed to structural hurdles, rejection, and resistance from within, to discrimination and marginalization by visitors, by opponents of this new process. This experience is characterized by other ambivalences: they feel empowered by self-representing and occupying space, by exposing privilege and asymmetries of power, while feeling uncomfortable because, fundamentally, many of these processes are being initiated for white, heteronormative recipients, who are already in positions of power, who are positioned at the epistemological center. We had no answer to the question if it was worth it to bring our activism from the outside into these places. And yet, although this space felt like a hopeless place, the diverse group of the discussion realized that they found love in our dialog and communion. And this is the greatest thing I have drawn from my own experience of working for the previous exhibition RESIST!. As bell hooks write: “We can begin the process of making community wherever we are. We can begin by sharing a smile, a warm greeting, a bit of conversation; by doing a kind deed or by acknowledging kindness offered to us. Doing this we engage in love practice […] we lay foundation for the building of community with strangers. The love we make in community stays with us wherever we go. With this knowledge as our guide, we make any place we go, a place where we return to love.”[3]

[1] http://www.rautenstrauch-joest-museum.de/Geschichte (accessed 28.04.2023)

[2] https://www.rautenstrauch-joest-museum.de/History (accessed 28.04.2023)

[3] hooks, bell. (2000) All about love: New Visions. HarperCollins, New York. pp. 141-143.

This blog is part of the Museum group.

In the course of the Decentering Epistemologies for Global Well-Being program, we (Clare Okidi based in Nairobi, Kenya, and Aminata Estelle Diouf based in Cologne, Germany) participated in the theme “Knowledge and Well-being” and formed the subgroup on the theme “museum.” We had many fruitful one-on-one discussions, where we discussed the role, that cultural museums played in our respective locations and cultural landscapes. For our fieldwork we both decided to visit museums that deal with cultural heritage, albeit each institution deals with the topic from a very different angle and with a very different perspectivity.

Clare went to the Nairobi National Museum, which was established in 1910 and is focused on the common history of the many different ethnic groups and cultural communities in Kenya reconnecting with the precolonial history and themes of national identity. Aminata visited the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum Cultures of the World, an ethnological museum in Cologne focused on non-European cultures. In recent years, the museum has been undergoing a critical transformative process in an effort to break with the way in which ethnological museums in Europe have been traditionally depicting world cultures and decentering Western epistemologies by enabling artistic/activist interventions within the museum space and by inviting marginalized cultural actors that do not typically take up space in these types of institutions.

What was interesting in our joint conversations was the realization that each of the museums was part of a larger opposing societal discourse. While the Nairobi National Museum was focused on fortifying the national identity and bringing together the different ethnic groups, the RJM museum, like many ethnological museums in Europe, has been at the forefront of discourses on marginalization, invisibility and exclusion of certain minoritarian groups within the dominant cultural landscapes of European countries. In our mutual reflection we realized that the museums should be playing similar roles to our societies but were in very different stages of that process: while the effort of the museum in Nairobi was to bring cohesion and inclusion to the communal divide that was once caused by colonialism, the museum in Cologne has become an important stage were minoritarian cultural actors were trying to have their own realities and perspectives acknowledged and self-representative perspectives included into the public spheres, breaking with the colonial narratives on their cultures and histories. In a way both institutions were places that gave space to processes of heritage and healing, which could contribute to well-being.

Embracing Diversity and Reclaiming Narratives: Nairobi National Museum, Kenya

About the author

Aminata Estelle Diouf is a PhD candidate at the University of Cologne, Germany