The Nairobi National Museum of Kenya

The Nairobi National Museum of Kenya is located on Museum Hill, Kipande Road, and it is 20 minutes from the Central Business District in Nairobi. It was founded in 1910. It is highly recognized for its rich resources for discovering, contemplating, and learning about Kenya’s pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial histories. The museum is visited by tourists, researchers, and members of the student community.

There are five attraction points within the museum, namely;

- Cradle of Human Kind Gallery

- Story of Mammals Gallery

- The History of Kenya Gallery

- Cycles of Life Gallery

- Numismatic Exhibition

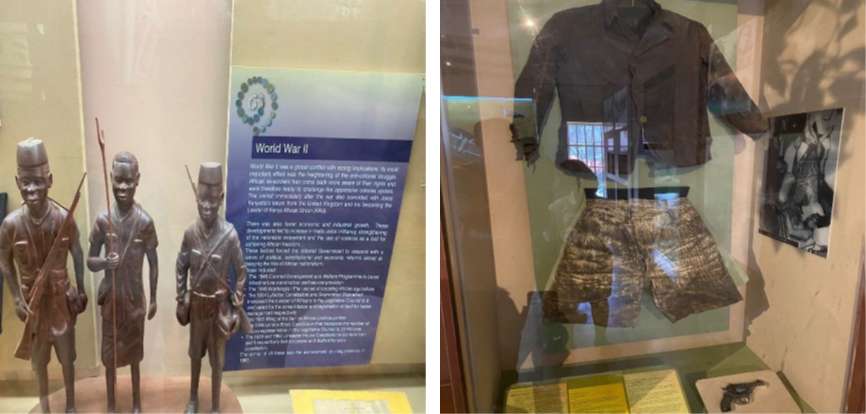

Our study covered the visitation of the ‘History of Kenya’ gallery’, where we were able to discover some interesting facts about the Mau-Mau fighters.

The Rebellion

The Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960), also known as the Mau Mau uprising, Mau Mau revolt, or Kenya Emergency, was a war in the British Kenya Colony (1920–1963) between the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), also known as the Mau Mau, and the British authorities. The Mau Mau movement of Kenya was a nationalist armed peasant revolt against the British colonial state, its policies, and its local supporters. The overwhelming majority of Mau Mau fighters and their supporters, who formed the “passive wing,” came from the Kikuyu ethnic group in Central Province. The movement also had representation from the Embu, Kamba, and Meru ethnic groups who fought against the white European colonist-settlers in Kenya, as well as the British Army and the local Kenya Regiment (comprised of British colonists, local auxiliary militia, and pro-British Kikuyu people). Dedan Kimathi was the leader of Mau Mau, Kenya’s armed independence movement. He is regarded as a revolutionary leader who fought against

British colonialists until his execution.

The armed rebellion of the Mau Mau was the culminating response to colonial rule in Kenya. Although there had been previous instances of violent resistance to colonialism, the Mau Mau revolt was the most prolonged and violent anti-colonial warfare in the history of the British Kenya colony. It was the Mau Mau movement that set the pace for Kenya’s independence from British rule or at least secured the prospect of black-majority rule once the British left.

Members of the Mau Mau are currently recognized by the Kenyan government as freedom and independence heroes and heroines who sacrificed their lives to free Kenyans from colonial rule. Since 2010, Mashujaa Day (Heroes’ Day) has been marked annually on 20 October. According to the Kenyan government, Mashujaa Day is a time for Kenyans to remember and honor the Mau Mau and other Kenyans who participated in the independence struggle. In 2001, the Kenyan government announced that

important Mau Mau sites were to be turned into national monuments. The memory of the Mau Mau brings out Kenya’s dark past, but it is also seen as a symbol of reconciliation to many Kenyans.

The Muringa Tree – A symbol of Resilience and Resistance of the Kenyan People

The Muringa Tree was originally located in the Aberdare Forest in Nyeri County, which is situated in the former Central Province of Kenya, about 153km north of Nairobi. The area is home to many Kikuyu people, who were predominantly Mau Mau fighters.

The Muringa Tree became a popular communication point from 1952 at the height of the Mau Mau uprising against British colonial rule. The Mau Mau Uprising was a rebellion against British colonial rule in Kenya that occurred between 1952 and 1960. The Mau Mau fighters used a symbolic oath-taking

ceremony under a sacred fig tree, known as the Muringa Tree, which they believed would give them supernatural powers and protection against their enemies.

The tree, known as the Muringa tree or the Mau Mau tree, became a potent symbol of the rebellion and was destroyed by the British authorities in an attempt to break the spirit of the Mau Mau fighters. However, this attempt proved futile as the resistance only grew stronger. The tree was located near

the town of Nyeri in central Kenya and was a meeting place for Mau Mau leaders who used it to plan their attacks on the British colonial government. It was also a primary medium of communication for the fighters, who would drop leaflets written in their language that only they could understand, using them to plan their attacks against the Europeans.

Although the original Mau Mau tree was destroyed, a new tree has been planted in its place as a symbol of resistance and resilience. The Mau Mau fighters are remembered as heroes in Kenya’s struggle for independence, and the Mau Mau tree has become a powerful symbol of their legacy.

To memorialize the legacy of the Mau Mau, an artificial tree has been placed in the Nairobi National Museum as a symbol of pride and freedom, paying homage to the fighters’ legacy. The leaves on the tree in the museum are symbolic representations of the number of leaflets or communications dropped off by the Mau Mau fighters. This is a famous historical heritage site visited by many tourists and academicians who delve deep to understand the past, present, and future relationships with many of these memorials.

This blog is part of the Memorials in Context group

Within our subgroup, « memorials », it was all about memories…memories of terrorist attacks in Germany, memories of armed resistance in Kenya, memories of African and Caribbean soldiers in London. We’ve been diving with ghosts in an ocean of memories, in public places, in a museum, in a health center… And we’ve been thinking: What would be linking those memorials together? Which history stays in people’s memories and which events get appropriated by institutions? How do memories get shaped?

Memory is a concept that allows one to create and hold a narrative of a moment or an event in the past. Each day we are presented with memory and tasked with how we want to carry it forward, in our history books, in the news, in our streets and within our personal lives. On an institutional level, those memories can often be determined and shaped for us by government or specific groups. But are they ever an accurate representation for those affected who have lost and cannot speak for themselves? We are faced with the question of who gets to tell one’s story and how, or who’s story is told and what conflict does it create? We find ourselves In an ocean of memories, where our future decisions are shaped by the lessons we learn from past events that have become memories, challenging us to understand how institutions shape our view and perspective of the past.

Memorials are found in various places, whether the physical locations of events, on houses or buildings, central spaces of cities or in remote places on the margins of social life. Monuments come in different forms and are sometimes more, sometimes less visible or recognisable as such. Their common feature is that they refer to a past that is worth remembering – or is or has been deemed to do so. Memorials are in some cases meant to remind us of our past while deepening our knowledge of how we relate with the future. Memorials, similar to other forms of institutionalized cultural memory, are intended to exist in perpetuity and thus point towards the future. However, social valuations are not constant at all, which is why memorials (from their emergence to their end of life) are always places of social and public debate, which also offer potential for conflict.

As part of our Global Classroom, we, Joseph, Meriam, and Fabian engaged with various memorials in Nairobi (Kenya), Rabat (Morocco), and Cologne (Germany). Here we describe our impressions and the process of our individual and collective engagement in separate articles.

The memorials we deal with have a wide thematic, aesthetic, pedagogical and historical range and could not be more different. The purpose of their existence also varies in the different contexts and cities we live in. In the course of our joint research and learning, we exchanged views on similarities and differences and thought about how we can nevertheless relate the different monuments, their local settings and meaning as well as our individual approach. The comparison and joint reflection during our exchange were of vital importance in order to get a sharper view of the site-specific context, implicit and explicit meanings as well as controversies developing around or emerging from the monuments.

In this process we encountered memory sites which deal with an artificial tree in the National Museum of Kenya remembering the Mau-Mau resistance (Joseph), the renaming of a healthcare facility in memory of a doctor from the French colonial epoch (Meriam), and non-existent memorials for the victims of right extremist violence in Germany/Cologne (Fabian). A common thread of the three topics and the local issues that emerge around them is a matter of memory upon the table of social negotiation. Public memory in terms of representation, participation and being recognised and making oneself recognised as a full part of society is linked to the question of social Well-Being, a concept we have to take up and at the same time deconstruct in our prismic perspective on the making of public memory.

When the Door of Memory Opens Up

About the author

Joseph Johnson is a Master’s student in Development Studies at the University of Nairobi, Kenya