The art of political satire in many African countries is not made for them who are not up for the challenge: journalists and satirists are often harassed and intimidated. One of the main goals for the harassment and threatening behaviour is to avoid critical review of the politicians involved. In Zambia, the freedom of the press and of expression are guaranteed by law, but other laws are rather restricting this ‘in the interest of the public order’. Then we have not yet mentioned that foreign nationals and journalist are lawfully deported at the moment they become a ‘threat to peace and good order’[1]. Isn’t that lovely subjective and handy for cranky MP’s (Members of Parliament or Metaphorical Parasites if you like).

Let us look at one great piece of the political satirist Roy Clarke, or Kalaki, published on the first day of 2004. Roy Clarke is a British expat, living in Zambia for over 40 years, writing since 1997 in The Post columns under ‘The Spectator’. Roy Clarke has many ideas as to why and how to hold leaders to account[2]. One of them is writing ‘in essence a textual version of cartoons’: accessible comparisons and metaphors to address political, cultural and legal hullabaloos. Below I would like to show you how he daringly ‘became a threat to peace and good order’, basically by showing that the ideas on ‘good order’ differ between politicians and citizens. On the same day, Clarke’s name was written on a signed Deportation Order.

In front of him sat all the assembled animals of Mfuwe, waiting for the Great Elephant Muwelewele to begin his Christmas Message[3].

Mfuwe is one of the three national game parks in Zambia and a touristic hotspot. It is metaphorically used: the allocation of power and funds is directed by and to the elites. In ‘the assembled animals of Mfuwe’ we can read National Assembly of Zambia.

Levy Mwanawasa was Zambia’s third president. Even though he got famous by his strong anti-corruption stance and taking to trial his predecessor Frederick Chiluba, Clarke shows here that with a mocking column, he became an enemy of the president[4]. Great Elephant Muwelewele is clearly based on President Mwanawasa.

‘When I was elected,’ continued Muwelewele, ‘I promised that only those constituencies that voted for me would see development. (…) ‘All the humans in the rest of this country refused to vote for me, so they have had no share in our marvellous development!’

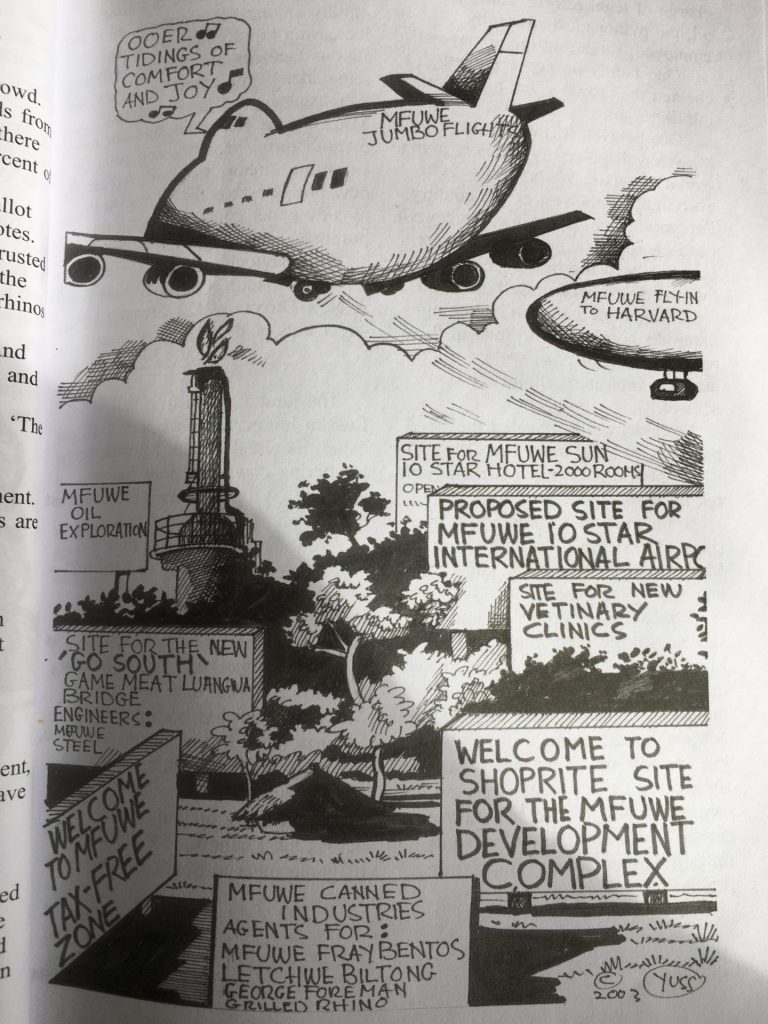

The rest of the country did not vote for Muwelewele: the victory of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy in 2001 was quite unexpected, because the opposition was in most of the polls on the winning hand. However, MMD won, because of the split in the opposition. Promising that only the ones who voted for the MMD would see development is based on finding voters in the ethnic and kinship spheres (something that is to be found in many African and non-African countries…). Marvellous development: a lot of money is pumped in the tourist sector, while other sectors of the economy are in a higher need for those funds.

‘So now the MMD is the Movement for Mfuwe Development. All my development programmes are located in Mfuwe and all my appointments are among you. The previous government would not put you in government, saying you were just monkeys and crocodiles, who shouldn’t be given the vote’. ‘Chamanyazi!’

MMD: Movement for Mfuwe Development instead of the ‘official’ Movement for Multi-Party Democracy. These type of corruptions of abbreviations are very common in Zambian satire. ‘they are studying for MBAs, degrees in Manipulating Budget Allocations’.

We also see a switch from English to Chinyanja, the third in the story. ‘Chamanyazi’ translated into English is ‘Disgraceful’. Clarke uses Chinyanja when he voices short reactions of the crowd of ‘assembled animals’ in front of the Elephant, he also uses ‘wehwehweh’ Zambian form of ululation, at a celebratory gathering.

I have nominated hippos to parliament, and made them my ministers. I have appointed jackals as my district administrators, and put the long-fingered baboons in charge of the treasury. I have put the knock-kneed giraffe in charge of agriculture, the hungry crocodile in charge of child welfare, and the red-lipped snake in charge of legal reform.

This part is particularly an attack on political and government leadership, and according to the politicians ‘including the people of Zambia’. The article was deemed culturally insensitive and racist, and the humorous side was completely ignored while issuing the deportation order.

Clarke, R. and Ford, T. (2004). The Worst of Kalaki and the Best of Yuss. Lusaka: Bookworld Publishers.

Eventually the deportation order was dropped after several court cases. It was discriminatory: it was aimed solely to Roy Clarke, and not to The Post or the editor of The Post who was responsible for the publication. It was flawed in several ways. Even though this case was threatening to the author, to the general public and journalism this case was opening up the democratic space and the culture of public criticism and shaming (Chama, 2012).

What is the nature of the insult in Zambia? Comparing (black) politicians to monkeys and baboons can be experienced as racist and provoking in many countries, in The Netherlands for example it would also not be acceptable. Yet the court case was dropped and Kalaki did not need to leave the country. Is he seen as the (national) jester? How important is a jester in an African country? And what does it mean that Kalaki is white? Quite the spectacle.

[1] For more information on this: Chama, B. (2012). Satirical Censorship in Press Practice in Zambia: The Case of Newspaper Journalist Roy Clarke. Africa Today, 81-90.

[2] See for example his Ted Talk at TedxLusaka: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8F4Z-t9PhI

[3] All the italics are quotes from the column are from: Clarke, R. (2004) 1.1 Mfuwe. The Worst of Kalaki and the Best of Yuss, 2-4)

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/media/2004/jan/07/pressandpublishing.g2