By Layla Farah and Marieke van der Heijden

Many countries in Africa struggle with finding enough doctors to work in the health sector. This leads to big problems in the healthcare system (The New Humanitarian 2009). In Nigeria, there is only one physician per 2674 people (Haseeb 2018). Problems tend to arise such as high work pressure for physicians and longer waiting lists for those who are unwell. This leads to many nationally trained doctors choosing to migrate to Western countries and practice medicine abroad. 28% of the sub-Saharan healthcare workers work in another country than the country that they are from (Haseeb, 2018). A reason often given for this is that the pay is much higher than in their country of origin. However, this is not the full picture. The article by Eddy Awire and Mamodesan T Okumagba (2020) shows that another part of the problem is the quality of medical education in Nigeria. There are issues in the lack of coherent admission policy, inadequate funding, poor planning and erosion of values. Awire and Okumagba state that Nigerian institutions are operating at a higher capacity than what they were initially designed for, which leads to a negative perception of the quality of education.

Awire and Okumagba conducted a two-phased mixed-methods study that consisted of a cross-sectional survey of final year medical students in four medical schools, and also semi-structured interviews. This led to some interesting insights into why many doctors tend to leave Nigeria.

In obtaining the quantitative data, students in their last year of studies were presented with a questionnaire. This questionnaire contained questions about their overall experience studying, but also about their experience with more specific services like support and facilities.

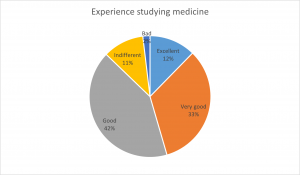

Most students have had a good overall experience studying medicine at a Nigerian university. As shown in the following graph, only 13% had an indifferent or bad experience. That means that 87% had a good, very good or excellent experience (Figure 1).

(Figure 1, experience studying medicine)

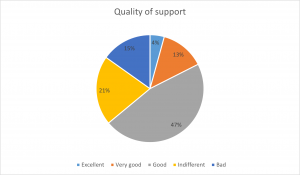

This is different when asked about the services support and facilities. 36% of students say that the quality of support was not good (Figure 2). 37% of students were not content with the quality of training facilities (Figure 3)

(Figure 2, quality of support)

(Figure 3, quality of training facilities)

When students were asked about their career plans, a distinction was made for a future in Nigeria or abroad. The numbers showed that 33% of students wanted to go abroad to get specialized training. Furthermore, only 9% of the students plan on practicing in the Nigerian health sector (Figure

4).

(Figure 4, post-graduation career plans)

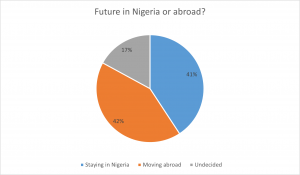

Further, the data showed that only 41% of the students have decided to stay in Nigeria. 42% have decided to move abroad, and 17% haven’t decided yet (Figure 5).

(Figure 5, future in Nigeria or abroad?)

If more students are planning on moving abroad than staying in Nigeria, there is a big consequence for the national health care system.

The qualitative data were obtained through semi-structured interviews with final year medical students, parents of the final year medical students, house interviews, resident doctors and faculty staff. The participant recruitment was conducted by contacting the school secretary’s office. Consequently, the study was introduced and those interested were given a letter detailing the study aims, and then snowball sampling was utilized. The data was managed by transcribing the interviews and then sorted into themes, categories and coding of the data.

The results of the interviews were categorized into different themes. Namely the quality of instruction, quality of medical training facilities, quality of support, experience studying medicine, frequent industrial action, and the desire to be the best and to be relevant. The interview provided a different life to the quantitative data and allowed the research to demonstrate more the perception of the study participant. For example, in terms of quality of instruction, the numerical data illustrate that 28% were critical of the quality of instruction in the Nigerian medical schools. However, the qualitative data showed that the reason for this is due to the fact that there seems to be a culture of just aiming to pass the exams, rather than acquiring the knowledge needed for professional practice. Moreover, a system of hierarchy takes place in Nigeria where students feel uncomfortable getting into discussions with their teachers. One student stated that “If they don’t like you, you are done” (Awire and Okumagba, 2020, p. 15). The interviews also illustrate that there is a lack of facilities that are either unavailable or nonfunctional, which means that the teachers and staff feel significant pressure delivering a medical curriculum with the lack of facilities. Moreover, many Nigerian medical students take a lot longer to finish their studies, even though they have never failed an exam, as this is due to the strikes that occur which is an obstacle to the students’ education. All of these hindering factors play a role in why students wish to migrate to another country, as they aspire to be the best in their field and wish to demonstrate that they are capable of more than there is to offer in Nigeria.

The mixed-methods study design of the two-phased methods gives the research more depth as it allows comparison between the quantitative and qualitative data, Furthermore, it reflects the participants’ point of view and gives the research more rich data. In this study, we can see that the survey data display satisfaction of the medical schools. However, if the data were to merely be quantitative, we would not know that there is deep dissatisfaction in what the schools have to offer and what the specific reasons for migration might be. Thus, mixed methods can give contradicting data, which is important because it goes into more depth and allows the research to reflect the true opinion of the topic at hand.

Bibliography

The New Humanitarian. “When there is no village doctor.” (2009)

https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/feature/2009/02/04/when-there-no-village-doctor

Haseeb, Saud. “The Critical Shortage of Healthcare Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comprehensive Review.” (2018)

Awire, Eddy, and Mamodesan T. Okumagba. “Medical education in Nigeria and migration: a mixed-methods study of how the perception of quality influences migration decision making.” MedEdPublish 9 (2020).