Given that Algeria had not yet gained independence against their French colonisers when Lumumba made his famous independence speech in front of King Baudouin in 1960, one would not naturally associate Algeria as being an influential actor in the Congo Crisis. However, as this project attempts to exhibit, Algeria not only played an influential role in the Congo Crisis, particularly in relation to the conviction and death of Moïse Tshombe, but also in the establishment of support and continual prolongation of the ideas espoused by Patrice Lumumba. In order to fully comprehend the nature of this relationship, one must first look to where this relationship first originated, at the Asian-African Conference at Bandung in 1955.

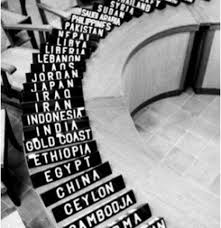

Whilst neither nation state had won their independence in 1955, the conference at Bandung would not only signal the first major meeting of its kind in the so called “Global South”, but it would also sow the seeds for cooperation between members of this “Global South” grouping under one united banner in the fight against European colonialism. One such figure to be heavily inspired by the events at Bandung was Patrice Lumumba, who would go on propagate the ideas fought for at Bandung in the form of the movement towards independence. Lumumba’s bond with Algeria, or rather Algeria’s relationship with Lumumba came through the esteemed revolutionary Frantz Fanon, honorary Algerian and close friend of Lumumba. Fanon had worked with the Algerian GPRA (Provisional Government) during its struggle in the Algerian War from 1954 – 1962 and key members of the GPRA were also invited to the Bandung Conference in a turn of events that would leave a lasting legacy in Algerian foreign policy, with the Congo Crisis emphasising this imprint. One of the major reasons for why this imprint lasted during the 60s was the almost unique scenario that Algeria found itself in. In the surge for independence, those who had fought and struggled as part of the FLN (National Liberation Front), and would also be members of the GPRA transformed into a single party that would go on to lead the country (Byrne, 2016). This point cannot and must not be neglected in the sheer scale of importance and influence that the FLN was able to garner following independence, with Algeria being one of the very few liberated African states whereby those who had fought and won independence would have a stronghold on power following the inception of independence.

Why is this important in the history of the Congo Crisis?

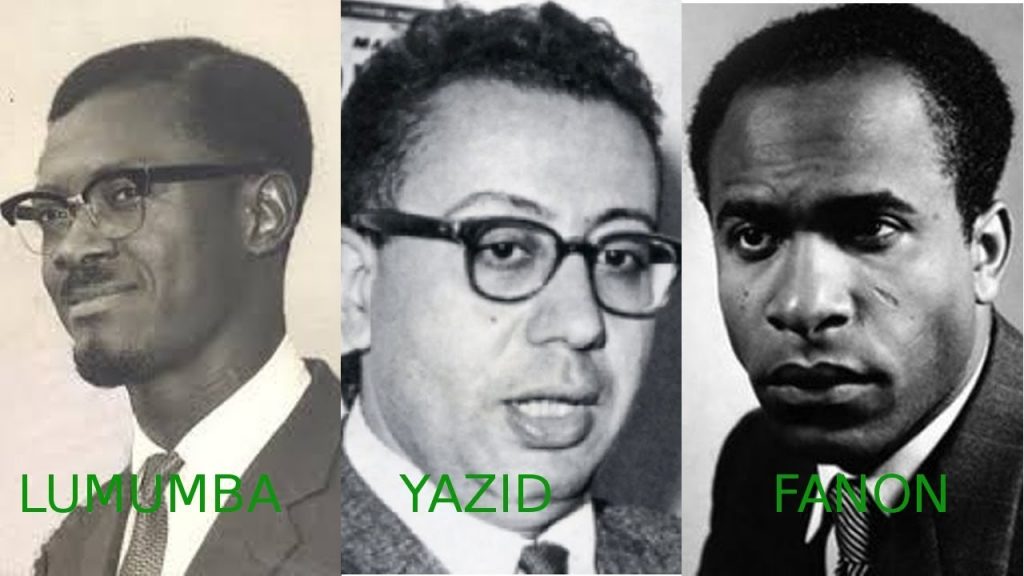

In Lumumba’s attempt to consolidate power following his accession to the post of Prime Minister as the Congo Crisis began to rear its ugly head, and having previously been in attendence at other All-African conferences which allowed for the type of networking that occurred in Bandung, Lumumba called upon his nationalistic friends across the continent in the search for support. Some of those present at the Inter-African Conference held at Leopoldville were the Algerian GPRA, led by M’hamed Yazid, an incredibly important figure in the Congo Crisis from an Algerian perspective and Frantz Fanon, himself, representing Algeria whilst supporting his close friend Lumumba in his hour of need in their attempts to fight off the forces they believed as being forms of neo-colonisation. In perhaps one of the only pieces of footage showing both Fanon and Lumumba together, this archived piece below highlights and emphasises the importance of African support from countries such as Algeria in supporting the increasingly powerless Lumumba in face of strong domestic opposition in the forms of separatism and foreign interference, as decrypted elegantly in Sapin’s painting (Pathe, 1960).

(Archives Pathé-Gaumont)

The obvious question then comes to mind, why were Algeria so invested in Lumumba’s project for the newly independent Congo and what were their own interests over their involvement in the subsequent Congo Crisis?

Again this brings us back to Bandung and the establishment of South-South cooperation in the newly developing world of independent African nation states. For Algeria, actively pursuing a “militant” foreign policy based on spreading ideals of “Third-Wordlism” and a “Bandung Spirit” became vital in both the development of nation building alongside the re-invention of what it meant to be an “Algerian” (Mortimer, 1984) . Following their struggle for independence, Algiers became synonymous as turning itself, with generous financial and military support from the Algerian government, into the “Mecca for revolutionaries”, whereby resistance groups across Africa such as Frelimo in Mozambique and the South African ANC would be hosted and aided in their own objectives of overthrowing colonial rule in their subsequent countries. This theme continues both across this project and the Congo Crisis, with involvement over the actions of Lumumba’s contemporaries acting as the perfect guise to spread Algeria’s version of “Third-Worldism” abroad, handily during times of internal disputes and growing pressure domestically. Actively seeking to support allies and fellow brethrens against the forces of occidental imperialism also served another purpose, those of Algeria’s, although not exclusively, plans for the restructuring of the global economic order which would better reflect the new found nature of the United Nations, with more and more decolonised states in the Global South bringing about a majority in the UN General Assembly, and with intelligent leaders such as Lumumba, these plans could forge themselves into reality. (Byrne, 2016). This is an important perspective which is sometimes neglected in the field of historiography regarding works on themes and movements such as Pan-Africanism and African Unity, in the age of decolonisation there was an intrinsic link between nation building and the continual promotion of these ideologies and often the two overlap, and this is evident in the case of Algeria and their actions regarding its involvement in the Congo Crisis.

It also becomes clear that the forces of Pan-Africanism played an important role in explaining Algeria’s actions in the Congo Crisis, with Fanon himself propagating the ideas espoused by Lumumba during his independence speech in June 1960. The need for both African unity and the total decolonisation in BOTH the political and economic spheres of Congo’s society would be the only way to guarantee Lumumba’s ambition turning into a reality, yet of course, the attempt to do this, given the power of foreign interference, meant that high risks were to be taken, and nobody knew that more than Lumumba himself as Fanon mentions in his work (Fanon, 1964).

This all points to an area of the Congo Crisis which is often overlooked in its historiography, given that more often than not when it comes to decrypting foreign influence and interference it tends to only come from the Western involvement of the crisis, something that this project will also delve upon with the aid of Sapin’s painting but this story presents the other side. The Algerian story and its involvement in the Congo Crisis does not end here however, it rather only begins.