Employing a Mixed-Methods Approach in an African Research Setting

BACKGROUND

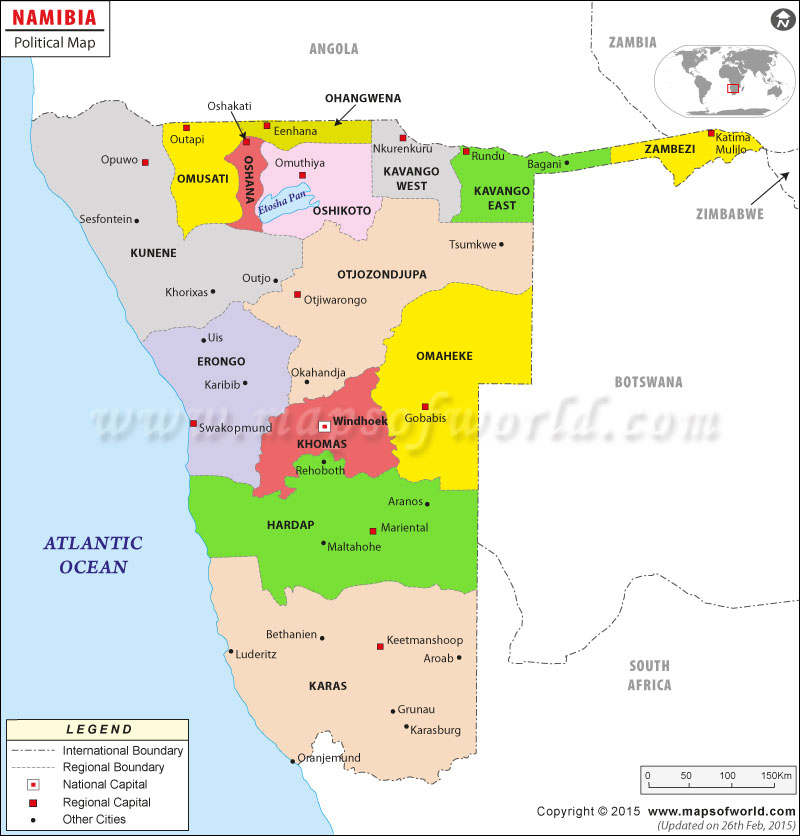

In Namibia, the terms “language” and “dialect” have been applied interchangeably and contradictorily in several linguistic and anthropological studies (Maho p.21 and following for this terminological challenge). Furthermore, Namibia’s language policy lists the following thirteen varieties as “languages” to be offered as language of instruction in schools: Afrikaans, English, German, Khoekhoegowab (Nama/Damara), Oshikwanyama, Oshindonga, Otjiherero, Rugciriku, Rukwangali, Setswana, SiLozi, Thimbukushu and Juǀ’hoan (MoEC 1993, 5-7).

Researchers Mashinja and Mwanza have focused their study on the SiLozi language. SiLozi is used

(SOURCE: Maps of World, 2021)

as a communication language in the Zambezi region in Namibia, yet it is not an indigenous Namibian language. Nonetheless, SiLozi is the instruction language in the junior primary in the Zambezi region. Its roots are of Zambian origin, and the majority of primary school students are taught in a language that is not their mother tongue.

Although SiLozi has a history of being taught back in mission schools and during the South African colonial regime, later, it did not become the native language for most people in the Zambezi region. The reasons to conduct primary education is SiLozi are purely political, and the language’s ‘main objective was to unite and harmonize the Namibian people of different linguistic backgrounds and avoid tribalism that will oppose national unity in education, economic, politics and social sectors’ (Mashinja & Mwanza 2020, 32).

MIXED METHODS

With this background in mind, let us go back to the article’s central question, ‘Is SiLozi appropriate in the Zambezi Region of Namibia?’. To analyze this, the authors have used a mixed methods approach, employing a convergent parallel design. This means that the researchers are incorporating both qualitative and quantitative research methods during the same phase of the research process, analyzing the results separately, but merging the findings in one conclusion.

The researchers used quantitative methods in the form of a familiar language test for pre-primary students. In contrast, the qualitative approach was carried out as a series of face-to-face interviews with six pre-primary teachers and six pre-primary students chosen from six schools across the Zambezi region. The data resulted was analyzed and discussed in relation to the effects on initial literacy development during the pre-primary school years, and how language exposure can influence the early stages of linguistic development.

"... since 1953, UNESCO has encouraged mother tongue instruction in early childhood and primary education. This implies that when a child is taught in a language that he/she is familiar with, learning is made easier because concepts will be easily understood."

FINDINGS

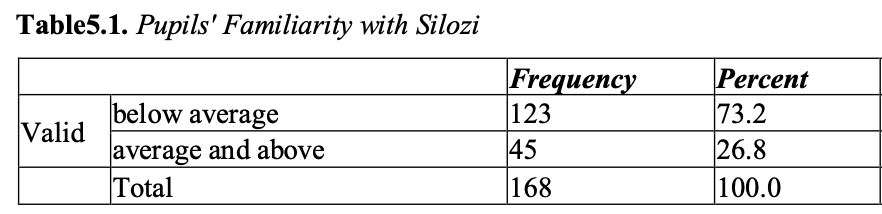

To test the students' familiarity with SiLozi, a language test was conducted in which each learner had to name a depicted image using the SiLozi language. They had to describe a total of twenty objects and based on their score, their familiarity would be decided (below 10/20 being unfamiliar). In table 5.1, the total outcome is depicted, showing 123 students scored below 10/20 (73.2%).

(SOURCE: Mashinja & Mwanza 2020, 36)

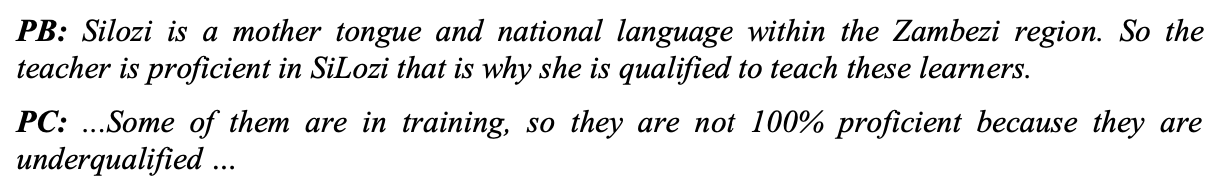

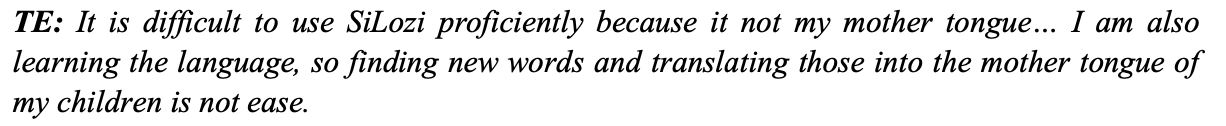

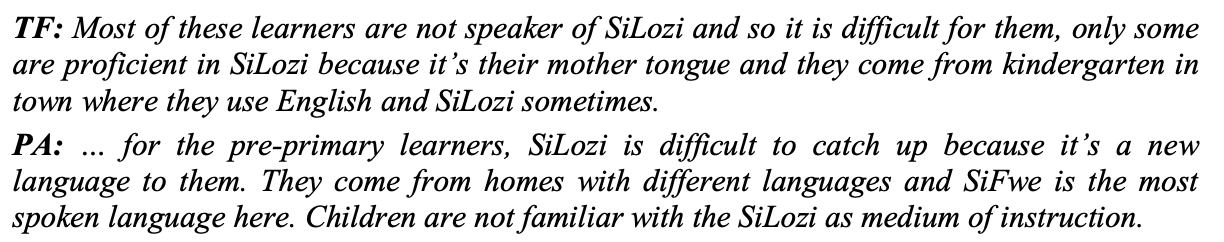

In the study, they tested both pupils' familiarity and teachers' familiarity. On the right, you can see some responses given by teachers and principals when asked about students' familiarity with SiLozi, during the interviews.

(SOURCE: Mashinja & Mwanza 2020, 37)

(SOURCE: Mashinja & Mwanza 2020, 35)

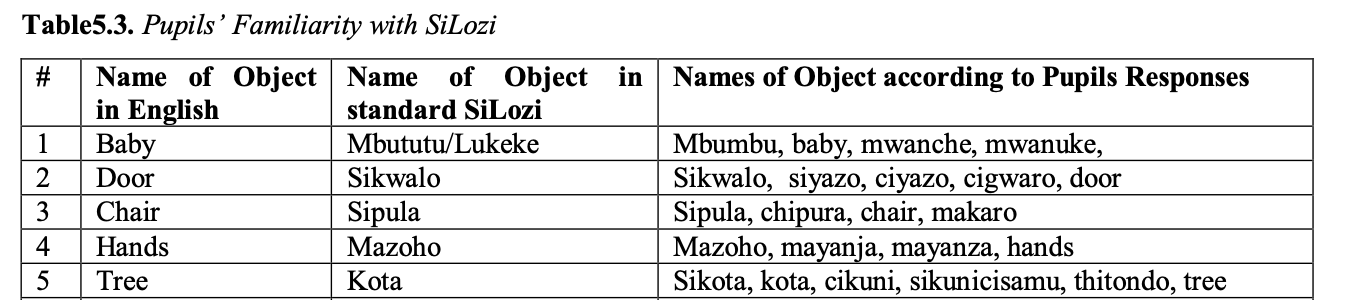

On the left (table 5.3) some examples are given of objects they had to name. Both the English and the SiLozi word are provided, and then finally the words used by the students to describe the object.

(SOURCE: Mashinja & Mwanza 2020, 36)

And finally, on the left you can first read to examples of answers given by principles, on the performance of teachers. Overall, it was not mentioned teachers were completely unqualified, but emphasis was put on the continuous training these teachers received to further improve. Secondly, teachers were also asked about their own performance, of which you can read an example on the left.

"They are not proficient. In fact, they don't understand SiLozi unless you translate in their mother tongue is when they can understand."

(SOURCE: Liseli 2020)

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSIONS

The main conclusions confirmed by the findings were that (1) pupils are not familiar with the SiLozi language and that (2) teachers are sometimes familiar with the SiLozi language.

First, the fact that most pupils are not familiar with the SiLozi language results in them not being able to develop literacy skills (in SiLozi) and poor achievements in education. Moreover, it causes a certain ‘voicelessness’ as their limited skills in SiLozi and limited literacy skills prevent them from thinking independently and involving in decision-making processes.

Second, most of the teachers were familiar with the SiLozi language, as they see it as a dominant language and use it in their (teacher) education and studies. However, they expressed that they experienced difficulties in teaching students who were not as familiar with the language. In addition, some teachers were not familiar with SiLozi which worsened the situation in the classroom.

The recommended approach to improving teaching in the classrooms, is to implement Translanguaging. Translanguaging “entails allowing students to draw from their home languages in the process of learning the target language and teachers accept it as legitimate pedagogical practice” (p.39). It thus utilises (multiple) local languages to support the teaching in SiLozi. The teachers should not discriminate pupils from the classroom interaction because they do not speak the SiLozi language of instruction. Instead, they should view local languages as legitimate modes of interaction which can support the teaching of literacy skills in/and SiLozi. This study as well as previous research demonstrate that this multilingual approach improves access to education, facilitates literacy development and aids pupils to acquire languages that are unfamiliar to them.

"Language as resource is considered inclusive in nature and integration as it accommodates and educates all children in the classroom, regardless of their linguistic and cultural background."

REFERENCES

- Liseli, Simon. "Zambezi learners back to school." The Caprivi. June 5, 2020. Link.

- Maho, Jouni Filip. Few people, many tongues: The languages of Namibia. Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan, 1998.

- Mashinja, Begani Ziambo, and David Sani Mwanza. "The Language of Literacy Teaching and Learning in a Multilingual Classroom: Is SiLozi Appropriate in the Zambezi Region of Namibia?" International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE), 7(2020): 31-42.

- Ministry of Education and Culture (MoEC). The language policy for schools: 1992-1996 and beyond. Windhoek: Longman Namibia. Link.

- Unknown. "Political Map of Namibia." Maps of World: Current, Credible, Consistent. Accessed on September 28, 2021. Link.