Podcast: Harrison Forman in Africa, 1961

Transcript:

Welcome listeners and interested parties to this podcast on the life and times of one of the greatest American photographers of the early and mid 20th century. Or, well, an African snapshot of his career, anyway. I am talking about Mr. Harrison Forman, born in 1904 and deceased in 1978, who those familiar with the history of Cold War journalism would know mostly from his well-documented exploits in China. Forman interviewed Mao Tse Tung in around 1945-1948 and published his Report from Red China and Changing China during that time. But, as I said, Mr. Forman’s most notable works in Asia are not the focus of today’s podcast. Instead, I want to take a closer look at the personal diaries he kept in 1961 on his travels through Angola and Congo. When he arrived in Angola it was on the cusp of the Portuguese Colonial War, which lasted from that year to 1974, a decisive ideological struggle in Lusophone Africa which involved all of its encompassing nations and mainland Portugal itself.

When Forman arrived in Luanda the Baixa de Cassanje revolt, which cost 400 indigenous Angolan plantation workers their lives, had already been suppressed. The subsequent influx of white Portuguese soldiers and settlers to bolster the colonial presence in the region gave Forman the impression that the western coast of Angola was predominantly European, that the 250.000 inhabitants of this region were predominantly whites; a transplantation of Portugal. The few Africans that he encountered as he mentions in his diary were mostly menial laborers. He goes on to express his surprise that whites in Angola work in all kinds of jobs, even those typically reserved for the lower classes. To quote Forman directly; “Room maids, waiters, even porters were whites. At Continental (the hotel chain) the porters average about 8 to 10 years old”. Forman finds this to be most unlike colonialism elsewhere in Africa such as in British, French or Belgian territories where Europeans came, quote; “to make money, as expatriates”. In Portuguese Africa however whites came explicitly to settle, with many lower class whites doing the same kind of work as they would on the continent.

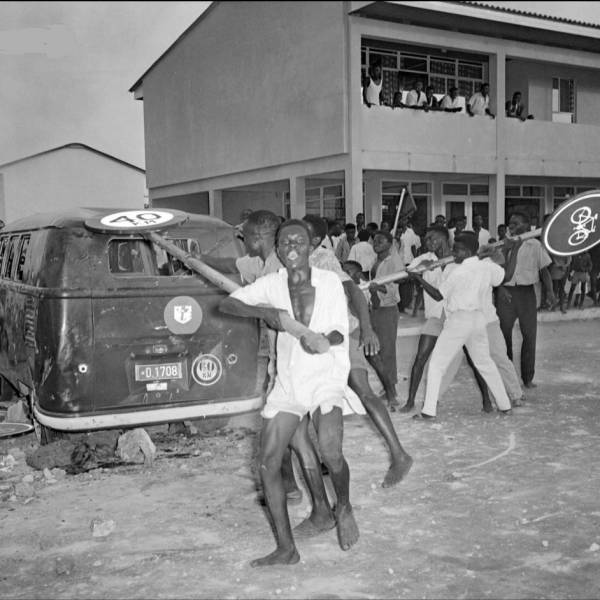

In an almost prophetic realization Forman remarks that the loss of Angola would be disastrous for Portugal, even more so then the loss of Congo was for Belgium. He says that Portugal would be nothing without Angola and that thus the Portuguese intend to hold on to it to the bitter end. The Portuguese reinforcements that came in from the mainland were greeted as heroes by the local European population and Forman had the opportunity to take many pictures of them. He describes the new arrivals as “fresh-faced youngsters” armed with state-of-the-art automatic weaponry and brand new fatigues. This is quite unlike the situation Forman found himself in when he had first arrived in Luanda, presumably during the immediate aftermath of the attack on Portuguese settlers by the FNLA leader Holden Roberto, which saw 1000 whites killed by around 5000 drunken and enchanted indigenous insurgents. Enchanted with tribal magic that convinced them that they were immune to bullets. The violence accompanying this insurgency received worldwide press attention and engendered sympathy for the Portuguese, while adversely affecting the international reputation of Roberto and his rebellion. While not explicitly mentioned in Forman’s diary, I presume this is why he journeyed to Angola in the first place.

This initially tense atmosphere in which the Portuguese, to quote Forman again, “shot first and asked questions later” subsided over the course of months. Rumours of violence against whites continued to spark reprisals from the Portuguese garrison against indigenous folk however, as Forman mentions a particularly gruesome case where an Angolan came into Luanda with the head of a settler on a pole. Naturally this angered the Portuguese greatly, but judging by Forman’s diary their retaliation was random and excessive rather than just and precise. Staking Angolans back, to put it crudely, was a common means of revenge practiced by the Portuguese garrison. Immediately after describing this serious violence Forman jumps to write about the abundant nightlife in Luanda, indicating that either some time must have passed in between or that the reality of war meant that dwelling overlong on the atrocious side of it is simply too depressing when you are in the thick of it.

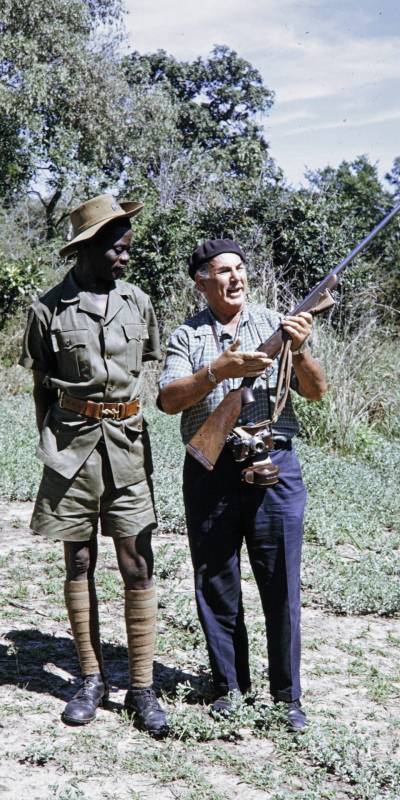

Be that as it may, the increased military presence in Angola is described by Forman as having a positive effect on commerce in Luanda. Soldiers shop at local stores, visit local nightclubs and engage in normal tourist activities, no doubt because many of them were born and raised in the homeland. Forman is told that the Portuguese economy as a whole is in recession, yet he describes Luanda as prosperous, with expensive Mercedes cars servicing as taxis in the streets. Shops are well stocked and new real estate construction is in full swing, but as Forman is told; “people are just not buying”. On the second to last page of his diary Forman describes the Angolan movie theaters, which are some of the best he’s seen on the African west coast. While going to the cinema he noticed that there were no black people attending, which he presumed to be because they could not afford a ticket. This is also where Forman’s diary ends. He continued taking dozens of pictures of the European locals and troops during his stay, all of which are available in the digital library of the University of Wisconsin, where Forman graduated with a degree in Oriental Philosophy.

Perhaps Forman’s reservations regarding indigenous self-determination stemmed from his experience in the newly independent republic of Congo. In the diary he kept while there in ‘61 Forman writes of the atmosphere after Congo gained independence from Belgium in 1960, one of widespread panic and increasing economic hardship. White Belgians, reportedly having fled the country after June 30th of 1960, left behind numerous belongings and valuables in a mad dash to get out of the former colony. The Congolese army later commandeered all these verhicles and seized all these belongings, only to resell them to local stores. Forman describes having heard about the violence that took place in this period, how it has now led to the mass closing of shops and companies all throughout Congo. Newly constructed high-rise buildings stand abandoned, save for the places captured by the UN personnel overseeing the transition to independence. The Congolese Franc has also inflated massively, making living very cheap, but hotels and other services have adjusted their prices to fixed rates in order to maintain a profit margin. Apparently an apocryphal story about Tunisia was doing the rounds in Congo, which at the time had just celebrated its first anniversary of independence. Congolese locals were joking that it must have been their third independence, as they “looked so white” and feared that Congo would go down a “white” path as well in the future. Forman actually comments on this idea himself when he describes the affairs going on at the immigration office, where business is slow because of the Congolese adopting the Belgian practices for their bureaucracy and thus, quote; “never being in a hurry”. He writes down an advice to Congo that if the country wants to catch up with an accelerated world, they had better forget what the Belgians taught them.

The contrast between the chaos in Congo after its independence and the continued sense of order in Angola, while the latter would definitely not last, signifies why Forman considered what he did in his diaries. As a well-traveled man who went to great lengths to be on the ground in Asia in the 1950’s and Africa in the 1960’s Harrison Forman experienced first-hand how Europeans engaged with their colonies in a period of decolonization. While it could certainly be said that all European control in Africa was living on borrowed time, Forman’s diaries illustrate the vision that I am sure many settlers and bureaucrats had at the time; maintaining an investment in Africa ensures a mutual benefit. Just how high a price one was willing to pay, that remained the eternal question.

Mirjam de Bruijn

September 30, 2020 (20:26)

Very informative and interesting pod cast; how to tell history. But the idea was as well that you would do some interview. Reading the diary is a form of interview of course. I really liked listening; but please think about how you want to become (a little bit) multi or interdisciplinary in your research.

The story you tell here is amazing though. The written text and the photo’s are also great.

An idea that came to my mind is that you could have read passages from the diary to have the voice of Forman in the podcast.