Introduction

As soon as the Congo became independent on the 30th of June 1960, the young nation became a battleground for Cold War superpowers, and colonial and white-minority regimes. They quickly took an interest in the newly established state. Congo was extremely rich in natural resources, particular in the provinces of Katanga and South Kasai. Belgium in particular, Congo’s former colonial overlord, tried to keep control over the Congolese economy. Belgian companies and affiliates controlled the Katanga mines and approximately seventy percent of the economy. The prelude to the independence of Congo began in 1959 following nationalist riots in Leopoldville. Belgium began to lose control over it colony as nationalist movements demanded the end of colonial rule. On the 30th June 1960, Congo gained independence from Belgium with Patrice Lumumba as prime minister and Joseph Kasavubu as president.

For a short time after its independence, the Republic of Congo became a beacon of hope for decolonisation in Africa. However, many important issues, such as federalism, tribalism and ethnic nationalism remained unsolved. Soon after the independence, internal violence erupted. Conflicts spread rapidly throughout Congo and engulfed the country into chaos. This period of socio-political chaos and disorder between 1960-1965 became known as the “Congo Crisis”. Power struggles and ideological differences characterized the conflict. Various leaders were fighting for control over the nation. What started as local protests quickly resulted in the secession of the Katanga and South Kasai provinces. Belgium, the United States and South Africa were heavily embroiled in the conflict as they supported the secessionist government in Katanga. The white-ruled regime of South Africa in particular had political interests in the Congo. They attempted to contain the spread of radical nationalism by undermining Congo’s central government. Congo became the target of external interventions, some of it under UN auspices. The intervention of the United States, as the preeminent superpower, Belgium, the former colonial power, and the enlistment of foreign white mercenaries made Congo a battleground for Cold War conflicts.[1]

South Africa and the Congo

In the early 1960s, the decolonising “wind of change” disintegrated the colonial administrations and white settler populations across the African continent. In South Africa, this tendency was inhibited by the white-dominated National Party’s policy of apartheid to protect the dominant position of the white minority. South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd ironically described apartheid as “a policy of good neighbourliness”. This policy was influenced by white anxiety of the black population, called the swart gevaar (black peril). The swart gevaar intensified in the early 1960s as the black population of South Africa became more vocal and increasingly militant in their demands for the abolition of apartheid and the implementation of the universal suffrage.[2] I analysed how South Africans reacted to the Congo Crisis between 1960 and 1963.

Literature on South Africa’s involvement in het Congo Crisis is surprisingly limited. The role of South African mercenaries during the Katanga secession and eastern rebellions is slightly covered. The reason that the South African government allowed mercenaries to fight in Katanga was to “fill the vacuum which had resulted from the withdrawal of the European powers.” The presence of white mercenaries showed the might of South Africa’s military to Africa. Support for the secessionist government of Katanga was to prevent the ensuing chaos in Congo to spill into the buffer states of Portuguese Angola and the Central African Federation. The Congo Crisis became a symbolic marker for the National Party to defend white minority rule in Africa.[3] Pretoria was aware of white mercenaries fighting in Congo and some government ministries even had contacts with them.[4] However, most of these histories were written by ex-mercenaries themselves, such as Michael Hoare, Hans Germani, Jerry Puren, and Ivan Smith. These eyewitness accounts convey the mercenaries own perspective of the crisis. Because these works give a one-sided image, I have chosen not to use these sources. The involvement of white-rule regimes in the Congo Crisis had often been described as an “unholy alliance” between Portugal, South Africa, and the Central African Federation. [5] This alliance was forged to protect white settler societies and to safeguard mining interest “from the Cape to Katanga”.[6]

For this research I had used six different South African national newspapers. These newspapers targeted a different audience. Die Burger was a Afrikaans newspaper, especially for the Cape Province, and aligned with the National Party. Huisgenoot was a popular family-orientated weekly Afrikaans periodical. Both targeted a white (Afrikaner) audience. The liberal periodical Contact had ties with the Liberal Party of South Africa and was limited critical. The quarterly Africa South, the monthly Fighting Talk and the weekly New Age supported multiracial resistance movements in South Africa. New Age and Fighting Talk were aligned with the left leaning Congress Alliance. Fighting Talk and Africa South reflected a broad spectrum of anti-apartheid opinions in South Africa.[7] Fighting Talk was banned of 1 March 1963 and New Age was banned in November 1962, because they were too critical of the apartheid regime. To give each newspaper an equal playing field, this research will cover the South African reactions to the Congo Crisis from 1960 to 1963. I tried to keep the number of secondary a few a possible to let the true voice of the South Africans speak through the sources.

Congo’s independence

In the months leading up to Congo’s independence, the people elected Joseph Kasavubu as president and Patrice Lumumba as Prime Minister. The Eisenhower administration hoped that the Republic of Congo would become an stabile, pro-western nation. These hopes were shattered as the newly independent nation erupted into chaos. On 5 July 1960 soldiers of the Force Publique mutinied against their white officers and subsequent conflicts between black and white civilians broke out. The mutiny rapidly spread throughout the country.[8] South-African newspapers and political magazines took an interest in the situation. Various movements within South-African society had different ideas about the future of the would-be Congolese nation. South African newspapers showed that there was a shared concern for the sudden call for Congo’s independence, but the interpretation and explanation of the situation differs.

South African left-leaning anti-apartheid activists were sceptical about Congo’s independence. A shared point of concern were the tribal rivalries in Congolese society. South African born political correspondent and anti-apartheid activist Colin Legum, who wrote a number of articles in the non-sectarian periodical Africa South, was critical about Congo’s sudden call for emancipation. Legum wrote that Congo’s future was “by no means assured”. He predicted that tribal frictions in Congo would ultimately lead to “large-scale inter-tribal massacres”.[9] Legum argued that “the crux of Congo politics was in the struggle between nationalism and tribalism.[10] According to Legum, Congo lacked the condition of a united government that could make independence successful. He argued that Congo could not fight the determined secessionist movements of Katanga and South Kasai and at the same time setting up a stable government.[11] In Fighting Talk, anti-apartheids activist Albie Sacks criticized the disunity among the political parties in Congo. He argued that as long as Congo’s parties were a reflection of tribal rivalries they posed “a serious threat to the unity and viability” to the new state.[12] Fighting Talk believed in an international conspiracy against Congo. It argued that “the problem in the Congo was not fundamentally a case of tribalism and primitivism run riot, but of a titanic clash between a new State and the combined afford of the West to undermine it.” The periodical reported that from the start of the independence, Lumumba had warned that “certain Europeans are plotting against the State.”[13]

A highlighted element in South African newspapers was the role of Congo’s former coloniser; Belgium. Anti-apartheid activists Legum and Sacks were worried about the impact of Belgian interests in Congo’s rich provinces. Fighting Talk was positive about the Congolese independence-developments, but argued that “the Congo still has a long way to go.” It wasvery critical about the role of Belgium in the transfer of power and argued that Belgian monopolies would be determined to maintain control of the country’s economic life.[14] Sacks suspected the Belgians of taking advantage of the political divisions to maintain their economic interests.[15] A reader in Africa South wrote that “our neighbour, the Congo, has been the victim of the policy of “divide and rule” and that efforts were being made by outside forces to disrupt the Republic and displace Premier Lumumba.[16] The Afrikaans family-orientated weekly magazine Huisgenoot was in particular very critical of Congo’s independence. It saw the transfer of Belgian colonial power to the Congolese as the flight of the civilising power. Huisgenoot reported that in the weeks up to the independence, Congo’s white population started to flee the country in fear of becoming a target of anti-white sentiment. The Flemish reporter Lode Stevens reported in an remarkable racist language, that there was no place anymore for whites on the black mainland, as the result of radical anti-white sentiment in Congo. Stevens described the departure of the white population as the result of primitive black Congolese coming from the ‘jungle’ to the urban area.[17]

Many South African newspapers argued that one of the greatest obstacles for Congo’s future would be the country’s political leadership. In particular Congo’s future president Joseph Kasavubu was a point of focus. In Huisgenoot, Stevens described Kasavubu as a black chief with a non-Christian name that was the reminiscent of black magic and an ebony-wood-coloured Mussolini. Stevens wrote that Kasavubu’s followers were nothing more than obtuse. The author even claimed that Kasavubu suffered from an inferiority complex similar to that of Mussolini and Adolf Hitler.[18] Africa South, a newspaper that targeted a black South African audience,traced Congo’s political instability to the “struggle between nationalism and tribalism”. It argued that it would “be a miracle if the Congolese leaders succeed in launching their experiment without any major tragedy.”[19] Anti-apartheids activist Legum went even further by dedicating the political incompetence to Kasavubu’s physical capabilities. He described Kasavubu physique as “short and squat, with mongoloid and Bantu features,” and his character as “suspicious and unforthcoming” with an “sly humour.”[20] Legum wrote in a style that was also common in the Belgian and American press. The goal was to delegitimise capabilities of political Congolese leader by referring to particular physical characteristics or negative adjectives.[21] Although some South Africans saw Congo’s independence as an good prospect for Africa. However, scepticism held the upper hand. Left-leaning periodical New Age blamed Belgian companies to “fan the flames of tribalism” if their interests in Congo’s riches were affected.[22]

The weeks after June 30th 1960, the day of Congo’s independence, violence erupted across the young nation. South African scepticism soon unfolded with the Force Publique mutiny and the Katanga secession. The Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger explained that the mutiny had removed the stabilizing military power with its white officers who were able to protect the white population. It worried that the growing anti-white sentiment, combined with the mutiny, would cause further uncertainty for Congo’s independence and success of the newly created republic.[23] In South Africa various explanations circulated why this violence had erupted in Congo and who was responsible for it. Die Burger blamed the Belgian government for the chaos as it was only interested in material benefits that it could get from its former colony. The author believed that, in the process of decolonisation, the Belgians had abandoned their own citizens when granting independence. This betrayal developed a Congolese disrespect for white people and thus started the violence.[24]

Violence

A more popular explanation for the violence was the ill preparation of the Congolese for the transfer of power. Many newspapers believed that without a common nationalism, loyalty, and stability Africa’s political emancipation would fail. The Congolese political consciousness was to obsessed with tribalism. In contrast, Contact did not attribute the chaos to the inability of the black Congolese people, but argued that the violence had erupted because of the universal effect on the collapse of authority.[25] Africa South searched for the answer in Congo’s colonial past. It argued that the cause of the violence “was a reprisal not just for individual acts of racial arrogance, but for history” as most of the assaults were “against Flemish-speaking settlers, whose reputation for racial tyranny was loud throughout the Congo, and against the families of Belgian army officers, who had clearly earned more rancour than regard from the African troops they had commanded.[26]

In the weeks following violence, destruction and chaos that swept across the Republic of Congo, a stream of white refugees had begun to fled from the country. It became an emotionally and debated topic in South African newspapers. With its dramatic style, Huisgenoot noted that years of hard work had turned into ashes by the Congolese who spawn hatred and death. Especially the impact of the dangerous situation upon children, women, and helpless people formed an important part of the report.[27] Fighting Talk believed that the chaos in Congo was the result of an international conspiracy and argued that the white people were fleeing because “the Belgium Government tried – successfully, as it happened – to panic its White subjects.” The aim of the Belgian policy was “to create that maximum confusion and alarm and to plunge the new state into chaos, so that Belgium rule could be restored.”[28] Africa South noted that it was unlikely that the number of white women raped and white people dead could be adequately established and as a result “one may wonder whether, of all the Congo atrocities, the press reports did not constitute the worst.”[29]

Soon after the mutiny, Moïse Tshombe declared the southern province of Katanga independent as the State of Katanga, with himself as President. Meanwhile, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu gained more power and influence in Congolese affairs. Fighting Talk suspected that the “jokers like Mr. Tshombe and Colonel Mobutu” worked together with the Western Powers. The author believed that “Mr. Tshombe could not survive for one moment without the support of foreign bayonets and the machinations of the Katanga’s White financial interests.”[30] A reader in New Age argued that “the three imperialist hirelings and stooges, Kasavubu, Tshombe and Mobutu, are only playboys for the time being.” He argued that the would “fade away when their own people rise against them.” New Age argued that “their case among the African-Asian nations is lost. In fact, these three do not belong to free Africa as Africa repudiates them.”[31] Fighting Talk heavily criticized the distorted image in South African and foreign newspapers about the crisis. Fighting Talk observed that in the initial days after the independence, the tone was positive, especially about Lumumba. However, many South African newspapers soon created an image of Lumumba “as a reckless, fanatical ally of Soviet Russia.” Fighting Talk argued that because of Lumumba’s alleged communist sympathies the Western nations “proceeded to try to destroy him.” The newspaper wondered why not a single South African newspaper conceded with “the basic fact that Mr. Lumumba was the legally elected Prime Minister of the Congo?”[32] All newspapers wondered how Congo would solve its internal problems.

Intervention?

A heavily debated topic in South African newspapers was the United Nations Operation in the Congo. The United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 143 on July 14, 1960 after a report by secretary-general Dag Hammarskjöld and a request for military assistance by Lumumba. Belgium contributed many soldiers to the operation. According to Kevin Dunn, the old colonial power believed that the Congolese “as children” needed fatherly guidance to solve its struggle.[33] Die Burger saw an foreign intervention to restore order and peace as obvious as the safety of many non-Congolese people was at stake. However, it argued that it was also problematic as Congo was an sovereign nation. Therefore, conflicts were an internal issue. Die Burger feared that Lumumba’s request for an foreign intervention would escalate into a full-scale internal conflict.[34] New Age disagreed with the view that the UN came as the liberator of the “oppressed peoples of the world” and argued that the intervention in Congo was a “disgraceful farce.” It linked the UN intervention to their fears of Western imperialism. New Age argued that the whole intervention was “a result of the intrigue of the Western powers who dominated the U.N.”[35]

New Age was especially critical about the intervention. It believed in a “plot of the U.S., Belgian and French imperialist to re-establish a new colonialism in the Congo”.[36] Lumumba was very dissatisfied with the refusal of Hammarskjöld to use UN troops for the intervention and appealed the Soviet Union for support. This split the government and let to increasing pressure form the Western powers to dispose Lumumba. Meanwhile, Mobutu took effective control of the military. On 5 September 1960, Kasavubu announced that he had dismissed Lumumba.[37] New Age called for the African states to intervene in the Congo Crisis instead of a UN intervention. It argued that the dismissal Lumumba, “a man who was elected Prime Minister by the people” from power, was illegitimated. Therefore the African states ought to “take speedy action to punish the Congo sell-outs Mobutu, Tshombe and Kasavubu – who have evidently been employed by the enemy to depose by foul means Patrice Lumumba, without any mandate from the people”. Action from the “UNO foreigners” was not going to help Congo. New Age saw it as the natural right of the “we Africans” to inherit the Congo. In their eyes Mobutu, Tshombe and Kasavubu only caused the Congolese people to kill each other.[38]

Lumumba’s dismissal as Prime Minister of the Republic of Congo in September 1960 caused protests by his supporters in South Africa. An African woman in Queenstown expressed her anger and disappointment in New Age. She called for the African states to intervene in Congo and “take speedy action to punish the Congo sell-outs – Mobutu, Tshombe, and Kasavubu.[39] New Age blamed the Western powers for the power change that had happened. It argued that the influence of the Western powers was reflected in the UN’s policy about Katanga, the disposal and arrest of Lumumba,[40] and the transfer of power to the “stooge of the Western imperialists” Joseph Mobutu.[41] New Age reported that Mobutu had overthrown the “legally elected Government of the Congo”. It claimed that under the cover of UN, imperialism moved back into the Congo and the independence aspirations of the people were “being drowned in blood.”[42] Fighting Talk argued that the crisis was the result of Belgian interference and argued that the future of Congo depended on the release Lumumba, the re-establishment of the elected Congolese parliament, and “disarming of Belgian-directed separatist Congolese forces”. It argued that by not defeating the secessionist forces in Katanga, the UN did not achieve its mandate to defend the independence and unity of Congo. [43] Fighting Talk argued that the UN subsequently played the country into the hand of the imperialists.[44]

Patrice Lumumba

Lumumba was by far the one on the most discussed political figures in South African newspapers. There were many different opinion in South Africa about his short period as Prime Minister, his arrest and tragic murder. Especially the black South Africans considered Lumumba as a hero and inspiring leader. A New Age reporter appealed to the Congolese people “not to listen to agitators like Kasavubu, Tshombe and Kalonji”, because there aim was “to divide Congo into small independent provinces in order that these Belgians may easily re-occupy the Congo and thus retard their progress.” New Age praised Lumumba as the man who had “done a lot of good” by trying to unite the differences in Congo. The formation of a central government by Lumumba would than “be a step toward to the United States of Africa.”[45] Lumumba was seemingly popular among some South Africans. A New Age reporter mentioned that he had heard a man burst out in Afrikaner “Kyk hoe mooi is die ‘laaitie’[46] ou Patrice Lumumba, die really, really leader van die Congo.”[47]

New Age sketched a very positive profile of Lumumba, attributing a kinds of traits to him. It claimed that Lumumba personified “the Congolese people’s demands for “Uhuru”, the freedom to rule over their own country and benefit in the wealth of Congo. It praised Lumumba as a freedom fighter who “bore the marks of the manacles on his writs.” According to New Age, Lumumba was the only man who could form a strong central government and “the only hope it tribalism and regionalism were not to deliver the country to Belgian rule under new forms.”[48] In contrast, Die Burger did not to approve Lumumba’s leadership at all. It blamed Lumumba for the violence and chaos as the crisis had erupted during his time as Prime Minister. Die Burger argued that Lumumba personified the revolutionary chaos in black Africa. In an overly racist language, it noted that Lumumba was a wild ape who jumped out of the jungle and forcing everybody to choose to be with him or against him.[49]

Kevin Dunn argued that the imagery of incompetent African leaders, such as Lumumba, was also common in Belgian newspapers that were published after Congo’s independence. They linked the behaviour of the Congolese to wild apes who recently came out of the trees.[50] The portrayal of Lumumba in Huisgenoot was similar as in Die Burger. It described him as an office clerk demagogue who was able to whip up the fanatical blood thirst of his people.[51] Colin Legum in Africa South was more positive, though nuanced. He wrote that of all Congo’s leaders, Lumumba was “earnest and tough and capable” for the future. However, Legum disapproved his political actions as his political movements were those of a “praying mantis.”[52]

In line with its readers, New Age described the dismissal of Lumumba as a plot between the Belgium and French government with the backing of the United Nations.[53] New Age blamed secretary-general Hammarskjöld for Lumumba’s disposal and “shameful” and “humiliating” imprisonment, only to be replaced Mobutu’s “military dictatorship”.[54] The South African Congress of Trade Unions called on January 1960 for the “democratic people throughout the world to fight for the release of Premier Lumumba, the popular leader of the people of the Congo.”[55] However, soon after this statement, it was announced on February 1961 that the Lumumba was murdered. Africa South blamed the Western capitalists and the Belgian government for the “covert accomplice” and indirectly pointed at the dubious role of the United Nations in the murder. Africa South argued that the United Nations did not followed its mandate properly, unnecessary had prolonged the crisis and ignored that fact that Lumumba was Congo democratic elected prime minister.[56] The South West African National Union published an statement in New Age that similarly pointed at the United Nations. It stated that the UN “would betray Africa” and that Lumumba’s murder was a clear example of that.[57]

Hammarskjöld and Katanga

General-secretary Dag Hammarskjöld was a central figure in a contested debate in South Africa about the UN intervention in Congo. Die Burger argued that the responsibility of the intervention rested in the hands of Hammarskjöld, because he was the only one who could influence the Security Council’s Congo policy.[58] New Age was by far the most critical of Hammarskjöld role. It suspected that Hammarskjöld, as a banker of the Sveriges Riksbank, the secretary-general would “always put investment’s before people”. New Age believed that this explained the UN’s decision for a “tough policy toward Premier Lumumba, who opposes foreign monopolies” and “a soft policy toward Moise Tshombe, the Katanga mining stooge.” New Age argued that under Hammarskjöld “colonialism survives a little longer” and “the traitor” Tshombe would be protected.[59]

When Dag Hammarskjöld’s airplane crashed in Ndola on September 18, 1961 under mysterious circumstances, criticism of his role in the Congo Crisis continued. New Age argued in an article with the headline “Q: Who Killed Dag?”, that Hammarskjöld died in the trap that he partially helped to create. It argued that Hammarskjöld bore a “large degree of responsibility” for his own death as had allowed the Katanga secession to continue and the military strength of Tshombe to grow. New Age argued that if the UN had honoured Lumumba’s request to restore Congo’s territorial integrity, the Katanga secession would have diminished and Hammarskjöld still be alive. It grimly states that “history has affected a grim retribution for Dag’s betrayal of the people of the Congo.”[60]

One of the most debated subjects in South Africa was the Katanga secession. Die Burger argued that an independent Katanga could be justified, but reasoned that a would-be Katanga independence would have “significant consequences for the future” as Congo relied on its resources. However, Die Burger feared that if Katanga would become independence, Congo would not be able to support itself.[61] Fighting Talk strongly opposed the independence of Katanga. It believed in an international conspiracy that allowed the Katanga secession to continue. Fighting Talk argued that the conspiracy was motivated by commercial interest in Katanga’s rich resources. It highlighted British and South African commercial interests in Katanga, including that of South African industrialist Harry Oppenheimer.[62] In an article headlined “Against the Winds of Change”, Fighting Talk explained that Oppenheimer was connected to Tanganyika Concession Limited, a company that owned ninety percent of the Benguela Railway Company that controlled the export of copper out of Katanga and a large portion of mining. Fighting Talk argued that the white-minority rule in South Africa had made an alliance with Katanga for commercial interests, such as Oppenheimer’s.[63]

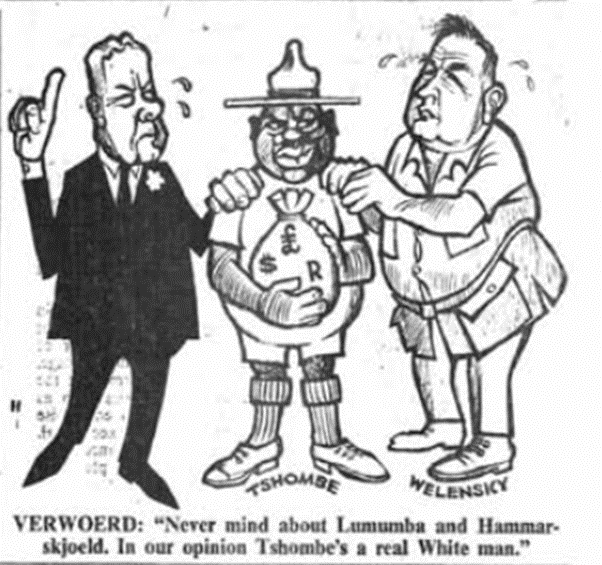

New Age believed in a similar conspiracy as Fighting Talk. It argued that “Roy Welensky, the British right wing Tories, the French ultras and the South African racialists” were fierce supporters of the Katanga secession. It stated that they had “bitterly resisted the African freedom struggle at every turn” and even had “the audacity to pose as friends of the rights of peoples to self-determination.” The strong persuasion of New Age in an international conspiracy against Congo inspired them to publish as cartoon (see figure 1) in which Roy Welensky, the Prime Minister of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and South African Prime Minister Verwoerd offered Tshombe as bag of gold. The message was clear. Welensky and Verwoerd were involved in the Katanga secession, because they had commercial interests. For this they would put aside their ideals about apartheid, but opt for pragmatism.[64] New Age believed that the UN had collaborated “with the enemies of Congolese independence, in particular with the Belgian mining companies.”[65] Surprisingly, after the announcement of the independence of Katanga, there were no articles about the Congo Crisis.

Death of Lumumba

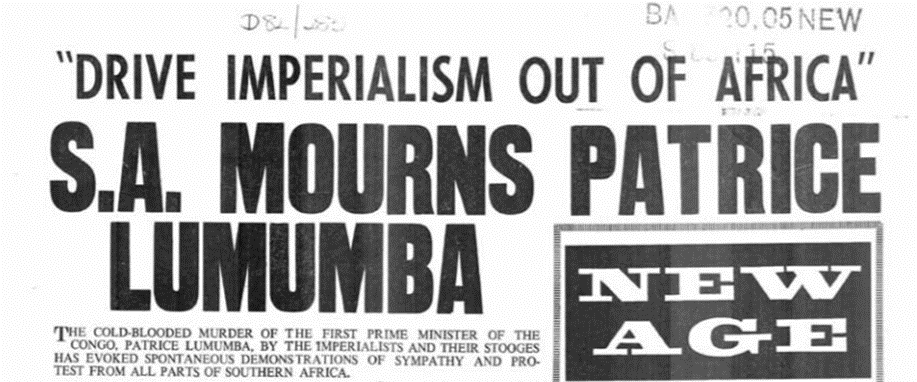

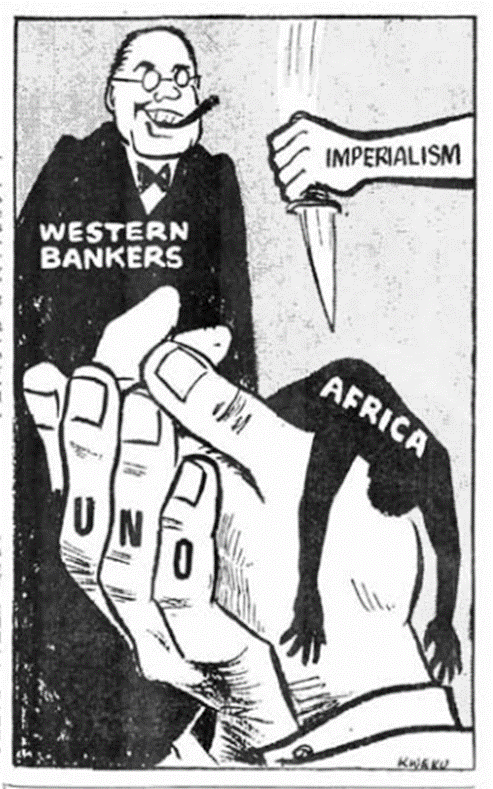

A major event that triggered renewed interest of South African newspapers in the Congo Crisis was the announcement of the death of Patrice Lumumba in February 1961. The news of his death caused violent actions against Belgian refugees who resided in South Africa. New Age reported on 23 February 1961 that “the cold-blooded murder of the first Prime Minister of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, by the imperialists and their stooges had evoked spontaneous demonstrations of sympathy and protests from all parts of Southern Africa.” It inspired New Age to publish this cartoon (see figure 2). The cartoon depicted het opposition of Western countries to kill black nationalism in Africa. New Age believed that the United Nations Organisation was driven by Western commercial interest who were only interested in profits. For New Age, Lumumba was the face of black Africans.[66] New Age urged its readers “to drive imperialism out of Africa” and demanded to “bring the killers to justice. Expose the African stooges of imperialism [and that] the United Nations secretary-general Hammarskjold must resign and the United Nations must be reformed to speak for the world’s peoples.” New Age accused Belgium and the United States, who “dominated” the United Nations, for the murder of Lumumba.[67]

The death of Lumumba created an unsafe situation for Belgian refugees in South Africa. A reader in New Age argued that the Belgians were “responsible for the present crisis in the Congo” and should be punished.[68] Another reader argued that “some may say the Belgian ‘refugees’ here had nothing to do with it. But why do they deserve our hospitality when their friends and themselves have a hostile attitude towards any person of colour’! What cheek they have! They ask for money for “refugee funds” and they arrive in our cities in big cars.”[69] It seemed that the murder of Lumumba sparked more than just frustration and anger towards Belgian refugees alone. Die Burger reported damage to automobiles with Congolese licence plates in Cape Town.[70] Contact reported that “the murder of Patrice Lumumba has shocked the world.” It called the murder of Lumumba a “sordid trick”, organised by Tshombe and Kasavubu.[71]

Lumumba’s death send shockwaves throughout South Africa. His death was often described as a personal loss by mourning South Africans. New Age described that murder of Lumumba as a loss of “their own leader – or brother.”[72] Many South Africans wrote condolences in New Age for Lumumba’s death. The S.A. Congress of Trade Union wrote that they “consider Mr. Lumumba to have been a great an glorious fighter for freedom”. Another reader wondered why Hammarskjöld had not protected Lumumba and allowed “Kasavubu to hand Mr. Lumumba over to Tshombe and the Belgians”. What point out was that these people saw Lumumba as their champion for equal rights and freedom for black Africans and that the “imperialists” and Belgians were to blame.[73] New Age used the situation in Congo to strengthen their claim against capitalism and imperialism. New Age argued that imperialist countries sowed unrest in Africa and were “fighting so hard to keep Katanga for the West” to benefit from it themselves.[74] Anger about the murder of Lumumba was not confined to readers columns in newspapers alone. New Age reported that commemoration were organised were people worn black mourning ribbons and that “the 29 accused in the Treason Trial stood with heads bowed in a silent demonstration against the murder of Lumumba at the morning tea break.”[75]

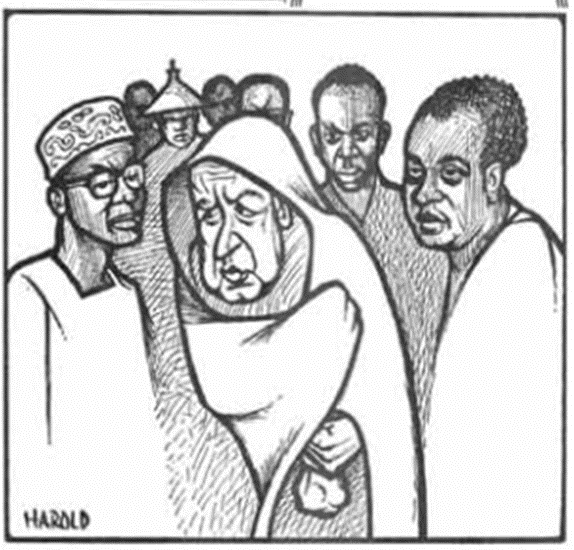

Lumumba’s death was sometimes described in biblical references. Some newspapers linked Lumumba’s death to the biblical story of Jesus’ betrayal by Judas and subsequent crucifixion and death. Irene Malaoa, in New Age, wrote that “a second Jesus has popped up in Africa, whose name was Patrice Lumumba and who also sacrificed for his own people”. She compared Lumumba to Jesus, because they had sacrificed their lives so that other “people could live in peace”.[76] Another reader wrote “that Jesus Christ was also beaten up by his captors, without mercy” the same as Lumumba was beaten during his captivity.[77] In similar rhetoric, another reader compared the betrayal of the Belgians to the betrayal of Judas. He stated that Lumumba was “not willing to sell the riches of his country for his own personal safety, and as the Belgian coloniser hoped, for 30 pieces of silver.”[78] Another reader mentioned that like Judas “who sold our lord for 30 shillings” the murderers of Lumumba would not get away with it either.[79] The comparison between Lumumba and Jesus inspired New Age to publish a cartoon titled “Judas 1961” with the caption: “who betrayed Lumumba for 30 pieces of Wes tern silver.” The cartoon depicted a shady cloaked Dag Hammarskjöld concealing a bag of money whilst finding his way through a crowd of black people. Just like Judas had sold Jesus Christ.[80]

The death of Lumumba was a great loss to many South Africans. Various commemoration, meetings, and gatherings were organised to mourn the death of Lumumba. The “Newclare Meeting”, which consisted of the South African Congress of Trade Unions, Transvaal Indian Congress, South African Coloured People’s Congress, and the Congress of Democrats, called on the “Afro-Asian countries to withdraw their UN forces from the Congo and to ensure the maintenance of Congolese independence”. They mourned and protested against the ”vicious, brutal and barbaric murder of the only legally elected Prime Minister of the Congo, Mr. Patrice Lumumba.” They showed their unanimous disapproval of murder by singing “Lihambile iQhawe Lama Qhawe u Lumumba” (Lumumba the Hero of Heroes is No More). A speaker at the meeting expressed his gratitude for Lumumba’s legacy by claiming that he was a “great leader of African liberation”, “a martyr” and a “staunch and unflinching fighter for African freedom.” A speaker of the Congress of Democrats claimed that Lumumba personified the “spirit of African freedom” and that he “stood for African independence and African unity against oppression.” To him, Lumumba was a representative of those objectives for which we in South Africa are struggling” [81]

A similar meeting was organised at Durban’s Bantu Social Centre. The place was, according to New Age, packed with an “angry but solemn crowd”. Apparently thousands of other people had to wait outside in the streets. South African Congress leader Gagathura Naicker gave a speech in which he accused Hammarskjöld for Lumumba’s death and argued that he had to answer “to the people of the Congo and the world for his bestial crime.”[82] In Cape Town, a similar meeting was organised by the South African Coloured People’s Congress and the Congress of Democrats. More than a thousand people gathered on the Grand Parade to mourn.[83]

One of the greatest gathering of people to mourn the death of Lumumba was at Veeplaas near Port Elisabeth. New Age reported that around five thousand people were present. The memorial service was opened by Reverend Maffanda who “based his sermon on the Biblical text “Where dogs have licked the blood of Naboth, there shall they lick the blood of murderers.” Govan Mbeki, one of New Age’s editors, accused the “imperialists” Belgian, American, and the French for collaborating with Tshombe, Mobutu, and Kasavubu to murder Lumumba. Mbeki demanded that that the Belgian and their “hired army of racialist desperadoes” were to leave from the Congo immediately and that the murders of Lumumba were “brought swiftly to justice.” A direct link was made to the young black South Africans. Mbeki urged them to see the death of Lumumba as a sign “dedicate themselves to sacred cause of nation al liberation.” Mbeki referred to Hammarskjöld as the protector of imperialism and national racialists in South Africa.[84] Lumumba was apparently a huge hero among the black Africans because a free poster of him was distributed with an attachment.[85] Apparently not all gatherings in South Africa were organised to mourn the death of Lumumba. A small group of members of the “Belgian Refugee Association” put up a poster in front of Johannesburg city hall titled “to hell with Lumumba and his communist friends. Why should we mourn for his death?”[86]

Lessons

According to many South Africans, lessons could be learned from the Congo Crisis. Examples from the Congo Crisis were used to expose abuses or legitimizing social-political actions in South Africa. New Age used examples from the Congo Crisis to strengthen their call for the abolition of apartheid. It warned the National Party to abandon apartheid or otherwise the country would soon face a similar fate as Congo. New Age argued that the reason why Congo had experienced chaos and violence, was because of the “unchristian law of apartheid”.[87] In similar rhetoric, a New Age reader warned Verwoerd to “wake up! What’s happening in Congo will happen to this country before 1963.” He urged Verwoerd to change his policies of apartheid. Otherwise he would find himself and his government “in the rut.”[88] Another reader in New Age warned for the unpopular plan of South Africa to transform Transkei into an independent nation, as “in the long run [it] may result in a crisis similar to that of the Congo”.[89]

On the other hand, South African newspapers that targeted a white audience used Congolese examples to justify their swart gevaar and defend apartheid. A reader in Die Burger argued that apartheid was the only way to solve the problems in South Africa. He justified his argument by stating that the Congo should serve “as a warning” to white South Africans what could happen if apartheid was abolished.[90] According to Huisgenoot there was an relation between the Congo Crisis and the increase of the swart gevaar. In an article about a women’s shooting club in Transvaal that was founded after protests in South Africa, Huisgenoot mentioned that news of the violence in Congo had fastened its pace. It reported that South African women wanted to defend themselves as they heard about the state in which some white female refugees arrived from the Congo in South Africa.[91] In another article, Huisgenoot argued that the white-minority regimes of Southern Africa should unite in a confederation that safeguarded the future of the white people in Africa. It stated that it was necessary to prevent becoming like the Congo.[92] Die Burger argued that the policy of apartheid should continue, because the violence in Congo legitimised it. Observing the chaos in Congo, Die Burger argued that black emancipation would not be possible as it had not worked in Congo either.[93]

A lot of references were made in South African newspapers to political figures who played a role in the Congo Crisis. A New Age reader complained that South Africa was “permeated with Tshombes, Mobutus and Kasavubus” and blamed Verwoerd “and his stooges” for the social-political problems.[94] It was also popular among the people as in a Johannesburg minimal wages campaign in 1962, the protesters slogans were “Don’t’ be a Tshombe” and “Tshombe sold the freedom of the Congolese. Don’t sell yours”.[95] Referring to Tshombe was not restricted to South African alone. Ambrose Zwane, the secretary of the Swaziland Progressive Party, stated that the “stooges, these Tshombes” who surrounding the Swazi king had a bad influence on him. Zwane urged that Swazi people to vote, because that was the only way that the “stooges” could be booted out “before they perform the Tshombe atrocity on the Swazi people.”[96] Another New Age reader warned the people of Transkei for Kaiser Daliwonga Mathanzima, the chief minister of Transkei and urged not to forget “Tshombe in the Congo”.[97]

Conclusion

The Congo Crisis was a heavily debated topic among South Africans. They followed the Congo Crisis with interest, but also with concern. They regularly voiced their opinions in columns that were seemingly close to their hearts. The topics that were thoroughly discussed were Congo’s independence, white refugees from the Congo, and political figures, such as Hammarskjöld, Tshombe, and Kasavubu. However, Patrice Lumumba was by far the most debated and contested figure among South Africans. He was condemned by many white South Africans and loved by black South Africans. Many black South Africans praised Lumumba as a hero and showed great sorrow and anger when he was murdered. They recognised in Lumumba as fighter for black African freedom and emancipation. His popularity was expressed as his death staged many protests and memorial services in honour of his legacy. However, many South Africans from across the racial spectrum also used the Congo Crisis and Lumumba’s legacy to strengthen their own purpose, political point of view, or ideas about the future of South Africa.

Newspapers used examples of the Congo Crisis to make sense of South Africa’s current realities and future direction. If South Africa was not to end up like Congo, they claimed that the country should implement apartheid or abolish it. South Africans followed the Congo Crisis closely, but their interest was in waves. It was not a debate that lasted the entire three years. White South Africans focused on the fleeing white refugees from Congo and reported less about Lumumba’s death. Black South Africans hardly discusses the refugees and reported in fierce language about the murder of Lumumba. The great number of publication showed that Lumumba was a great hero among black South Africans. It seemed that they used this example to strengthen their claim to political participation and black nationalism. An overall analysed showed that the black South Africans use the Congo crisis to a large extent for their own purposes. They used Congolese examples to emphasize their struggle against imperialism, oppression and exclusion. Thus way of rhetoric is muss less visible by white South Africans. They used examples to substantiate the existing apartheid situation in South Africa.

Bibliography

Secondary sources

Ainslie, Rosalynde, Basil Davidson, and Coner O’Brien, The Unholy Alliance, Salazar – Verwoerd – Welensky (London 1962).

Clarke, Stephen, The Congo Mercenary: A History and Analysis (Johannesburg 1968).

Devlin, Larry, Chief of Station, Congo: A Memoir, 1960-1967 (New York 2007).

Dunn, Kevin C., Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity (New York 2003).

Harrison, David, The White Tribe of Africa: South Africa in Perspective (California 1982).

McDonald, Peter D., The Literature Police: Apartheid Censorship and Its Cultural Consequences (Oxford 2009).

Nzongola-Ntalaja, Georges, The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History (London 2002).

Puren, Jerry and Brian Pottinger, Mercenary Commander: Col Jerry Puren as Told by Brian Pottinger (Alberto 1986).

Schmidt, Elisabeth, Foreign Intervention in Africa: From the Cold War to the War on Terror (Cambridge 2013).

Vanthemsche, Guy, Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980 (Cambridge 2012).

Primary sources

Fighting Talk

Contact

New Age

Huisgenoot

Die Burger

Africa South

[1] Larry Devlin, Chief of Station, Congo: A Memoir, 1960-1967 (New York 2007); Elisabeth Schmidt, Foreign Intervention in Africa: From the Cold War to the War on Terror (Cambridge 2013) 56-77.

[2] David Harrison, The White Tribe of Africa: South Africa in Perspective (California 1982) 166.

[3] Stephen Clarke, The Congo Mercenary: A History and Analysis (Johannesburg 1968) 35.

[4] Jerry Puren and Brian Pottinger, Mercenary Commander: Col Jerry Puren as Told by Brian Pottinger (Alberto 1986) 196.

[5] Rosalynde Ainslie, Basil Davidson, and Coner O’Brien, The Unholy Alliance, Salazar – Verwoerd – Welensky (London 1962) 2-3.

[6] Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, The Congo from Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History (London 2002) 32.

[7] Peter D. McDonald, The Literature Police: Apartheid Censorship and Its Cultural Consequences (Oxford 2009) 119

[8] Guy Vanthemsche, Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980 (Cambridge 2012) 94.

[9] ‘The Belgian Congo (ii) Towards Independence’, Africa South (September 1960) 78.

[10] Ibidem.

[11] Ibidem, 79.

[12] ‘Africa Round-Up’, Fighting Talk (March 1960) 11.

[13] ‘The Newspaper War for the Congo’, Fighting Talk (October 1960) 11, 14.

[14] ‘Africa Round-Up’, Fighting Talk (March 1960) 11.

[15] ‘Africa Round-Up’, Fighting Talk (March 1960) 11.

[16] ‘Northern Rhodesia’s Time For Change’, Africa South (July 1960) 72.

[17] ‘Dolle Vlug van Blankes uit Die Kongo’, Huisgenoot (May 1960) 11.

[18] ‘Swart Koning van Kongo’, Huisgenoot (May 1960) 8.

[19] ‘The Belgian Congo (ii) Towards Independence’, Africa South (September 1960) 78.

[20] Ibidem, 83-85.

[21] Kevin C. Dunn, Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity (New York 2003) 83–84, 91-92.

[22] Congo Free on June 30’, New Age (25 February 1960) 7.

[23] ‘Muitery in die Kongo’, Die Burger (7 July 1960).

[24] ‘Geen Benul van Afrika nie’, Die Burger (26 August 1960).

[25] ‘The Congo’, Contact (16 July 1960) 2, 5.

[26] ‘The Heart of Darkness’, Africa South (December 1960) 1.

[27] ‘Hartseer-Vlug uit die Kongo’, Huisgenoot (29 July 1960) 14-15.

[28] ‘The Newspaper War for the Congo’, Fighting Talk (October 1960) 11.

[29] ‘The Heart of Darkness’, Africa South (December 1960) 1.

[30] ‘The Newspaper War for the Congo’, Fighting Talk (October 1960) 11.

[31] ‘Belgians Must Go’, New Age (23 February 1961) 2.

[32] ‘The Newspaper War for the Congo’, Fighting Talk (October 1960) 11.

[33] Dunn, Imagining the Congo, 70-71.

[34] ‘Inmenging in die Kongo’, Die Burger (13 July 1960) 27.

[35] ‘U.N. Is Failing Africa’, New Age (8 December 1960) 2.

[36] ‘Lumumba Must Be Freed’, New Age (8 December1960) 7.

[37] Vanthemsche, Belgium and the Congo, 202-203.

[38] ‘African States Must Intervene in Congo’, New Age (2 February 1961) 2.

[39] Ibidem.

[40] ‘Lumumba Must Be Freed’, New Age (8 December 1960) 7.

[41] ‘U.N. Is Failing Africa’, New Age (8 December 1960) 2.

[42] ‘U.N. Is Failing Africa’, New Age (8 December 1960) 2.

[43] ‘The Congo’, Fighting Talk (February 1961) 9.

[44] ‘The Congo Crisis and the United Nations’, Fighting Talk (23 August 1960) 8.

[45] ‘Stand by Lumumba’, New Age (22 December 1960) 2.

[46] Afrikaans slang for boy or young adult male.

[47] ‘New Age Was Spanned Up in the Townships’, New Age (22 September 1960) 6.

[48] ‘Patrice Lumumba: They Can’t keep Him Down’, New Age (22 September 1960) 7.

[49] ‘Uit My Politieke Pen’, Die Burger (18 February 1961).

[50] Dunn, Imagining the Congo, 70.

[51] ‘Pres Tshombe se Wit Troepe’, Huisgenoot (12 May 1961) 8-9.

[52] ‘The Belgian Congo (ii) towards Independence’, Africa South (September 1960) 83-85.

[53] ‘Stand by Lumumba’, New Age (22 September 1960) 2.

[54] ‘The Two Faces of Dag Hammarskjold’, New Age (12 January 1961) 2.

[55] ‘PE Workers out to Win’, New Age (2 February 1961) 1.

[56] ‘Case History in Suicide’, Africa South (June 1961) 1-4.

[57] ‘South West Africa blames UN’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[58] ‘VVO ‘Kolonialisme’, Die Burger (15 August 1960).

[59] ‘A Banker Directs UN Activity in Congo … And His Name Is Dag Hammarskjold’, New Age (9 February 1961) 6.

[60] ‘Q: Who Killed Dag? A: Dag’, New Age (28 September 1961) 6.

[61] ‘Die Vraagstuk van Katanga’, Die Burger (20 July 1960).

[62] ‘SA Bantu Football Association Rejects Tshombe Initiative, Fed Up with Stooges’, New Age (9 February 1961) 2.

[63] ‘Against the Winds of Change’, Fighting Talk (July 1962) 7-9.

[64] Cartoon in: New Age (28 September 1961) 3.

[65] ‘Tshombe Must be Punished’, New Age (21 September 1961) 5.

[66] Cartoon in: New Age (23 February 1961) 2.

[67] ‘S.A. Mourns Patrice Lumumba’ New Age (23 February 1961) 1.

[68] ‘Belgians Must Go’, New Age (23 February 1961) 2.

[69] ‘Belgians don’t Deserve our Hospitality’, New Age (23 February 1961) 2.

[70] ‘Vlugteling uit Kongo se Motor Verniel in Kaap’, Die Burger (8 March 1961).

[71] ‘The Murder of Lumumba’, Contact (25 February 1961) 4.

[72] ‘SA Mourns Patrice Lumumba’, New Age (23 February 1961) 1, 4.

[73] ‘More Condolences on Lumumba’s Death’, New Age (16 March 1961) 2.

[74] ‘Africa Needs Capital for Development’, New Age (16 March 1961) 2.

[75] ‘S.A. Mourns Patrice Lumumba’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[76] ‘Lumumba Died for Us’, New Age (13 April 1961) 2.

[77] ‘Congo Murderer’, New Age (23 February 1961) 2.

[78] ‘Dag Must Answer’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[79] ‘Our Readers Condemn Lumumba’s Murder’, New Age (23 September 1961) 2.

[80] Cartoon in: New Age (2 March 1961) 5.

[81] ‘Newclare Meeting’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[82] ‘Dag Must Answer’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[83] ‘Cape Town’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[84] ‘5,000 at PE Protest’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[85] ‘Lumumba Portrait for New Age Readers’, New Age (23 February 1961) 4.

[86] ‘Belgians Will Quit Union Soon’, New Age (2 March 1961) 2.

[87] ‘Apartheid Is Jungle Law’, New Age (22 September 1960) 2.

[88] ‘Stand by Lumumba’, New Age (22 September 1960) 2.

[89] ‘Our Readers Condemn Lumumba’s Murder’, New Age (9 November 1961) 2.

[90] ‘Kongo Los vir ons Niks op nie’, Die Burger (27 September 1960).

[91] ‘Vroue Gryp die Roer’, Huisgenoot (23 September 1960) 24.

[92] ‘So het Katanga Gelyk’, Huisgenoot (22 September 1961) 72.

[93] ‘Die Kongo en Ons’, Die Burger (11 July 1960).

[94] ‘Union also has its Mobutus’, New Age (4 March 1961) 2.

[95] ‘Flying Start to SACTU Campaign’, New Age (15 February 1962) 1.

[96] ‘One Man One Vote’ for Swaziland’, Fighting Talk (October 1961) 11.

[97] ‘Beware of Matanzima’, New Age (12 April 1962) 2.