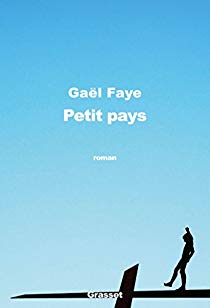

Before coming to the Netherlands, and to Leiden University, I complained to my brother that I did not have enough space in my luggage to bring books with me for the year. On the day I was leaving, he eventually gave me his Kindle, that was passed on to him a few years earlier by a friend and that was pretty much used as a common commodity in my old neighborhood. “200 books in about 300 grams, how cool is that?” I was skeptical at first. I don’t like reading on screens. I like to physically turn pages and feel that I have gone through the text. The tablet did not look so appealing, especially with that rough and quite damaged shell. But I was not planning on buying any more books so that revealed to be a convenient gift. I gave it a try and checked the list of titles already downloaded on the device. Along with the eight Harry Potter’s, other many young adult literary pieces, and the surprising number of books in Spanish, the tablet had a few interesting novels written by Algerian activists and other African writers. Assia Djebar, Yasmina Khadra, Kamel Daoud, Albert Camus. And, Gaël Faye, Petit Pays.

Petit Pays is a self-inspired novel written by author and musician Gaël Faye. It was published in 2016. The two hundred and twenty-four pages relate the life of Gabriel, nicknamed Gaby, a 10-year-old boy, who lives a peaceful and happy childhood in the residential expat district of Bujumbura, Burundi, with his family – his sister, Ana, his French father and his Rwandan mother. However, his well-being quickly takes a turn, when the geopolitical tensions of Burundi and Rwanda reaches him. The first democratic elections in Burundi and the Rwandan genocide threatens his world and insecurity as well as death becomes part of his daily life.

Gaël Faye offers a spontaneous account of the tragedy, of events he actually lived, through a child perspective that is not totally his. But why make this narrative the discourse of a third party?

An hybrid genre to free the words

Gaël Faye wrote Petit Pays as a novel. He asserts that it is not autobiographical but self-inspired. Indeed, it appears that the author’s and narrator’s lives greatly overlap. Both Gaby and Gaël are French-Rwandan, were born and raised in Burundi and suddenly forced to expatriation to France in 1995, at only 13 years old. And, they only got the chance to go back to Bujumbara way later, when in their thirties. This hybrid literary genre may enable Faye to write more freely, by distancing himself from his own past and making Gaby go through it instead of him.

Writing to heal

The book is a first-person narrative. When reading Petit Pays, we embody Gaby with this “I”. We go through his childhood and we share his small joys as well as his suffering. We understand that putting words on these feelings might have been necessary to let them go. In the story, when things start going downhill in the country, Gaby seeks refuge in his Greek neighbor’s library. He tries his best to escape to other worlds through her books. Along the way, he starts writing more poetic letters that gradually reveal his feelings.

Highlighting the absurdity of the ongoing tensions

In his book, Gaël Faye makes use of humor to tackle the political issues. The innocence of the child’s perspective enables to naturally reveal the humorous aspect of situations. In a prologue that begins with a conversation between the narrator and his father, the child asks why the Tutsis and the Hutus are fighting. “Because they do not have the same nose” answers the father to stop the discussion. After that, Gaby finds himself checking on everyone else’s nose to figure out what group they belong to. In line with this extract, along the whole book, Faye switches between grave moments and lighthearted thoughts.

In 2012, Gaël Faye offered a sneak peek into what has become the literary best seller that Petit Pays is with his eponymous song. Hear it out below. When Faye raps in French, the song is punctuated by melodious words in Kirundi. The lyrics are also a constant back and forth between Africa and Europe. Through these combinations, he claims his dual background and belonging. Though, it seems that Faye is lost somewhere between the two. “Et nous voilà perdus dans les rues de Saint Denis” “Bujumbara, tu es ma luciole dans mon errance européenne” There is movement in his words. In the Parisian suburbs, he is wandering around and cannot settle in. Maybe his book finally gave him the opportunity to go back to a time he needed to dive into.